Professor Kayoko ITO works on a range of social welfare and social work studies, including a foster care support model, as we discover here

Since April 2021, I have been a visiting researcher at the University of Glasgow, where I am conducting research on social work to prevent foster care breakdown. By way of background to my study, it’s important to say that the United Nations has many times now, recommended that improvement is needed in the Japanese social foster care system. The five main points concerning their recommendations are as follows.

1) The lack of ‘home-based care’ (foster care and adoption).

2) The mainstream of institutional care has been a ‘Large Building System’.

3) Group care in ‘infant home’ (for those between 0-2 years old).

4) The number of children handled by each social worker in Child Guidance Centres should be reduced.

5) A system should be created where children in and out of care express their views and let their voices be heard.

In response to the UN recommendations for improvement, Japan has been reforming its social foster care system since 2011. Specifically, this means “shifting from institutional care to home-based care,” and Japan has been promoting foster care by setting a high foster care placement rate as a goal.

However, as the rate of foster care placements has increased, so has the number of cases that lead to foster care breakdown. What is the background to this? One possible reason is that the number of foster parents has increased, and the number of children placed to foster families has increased without improving the support system for foster families.

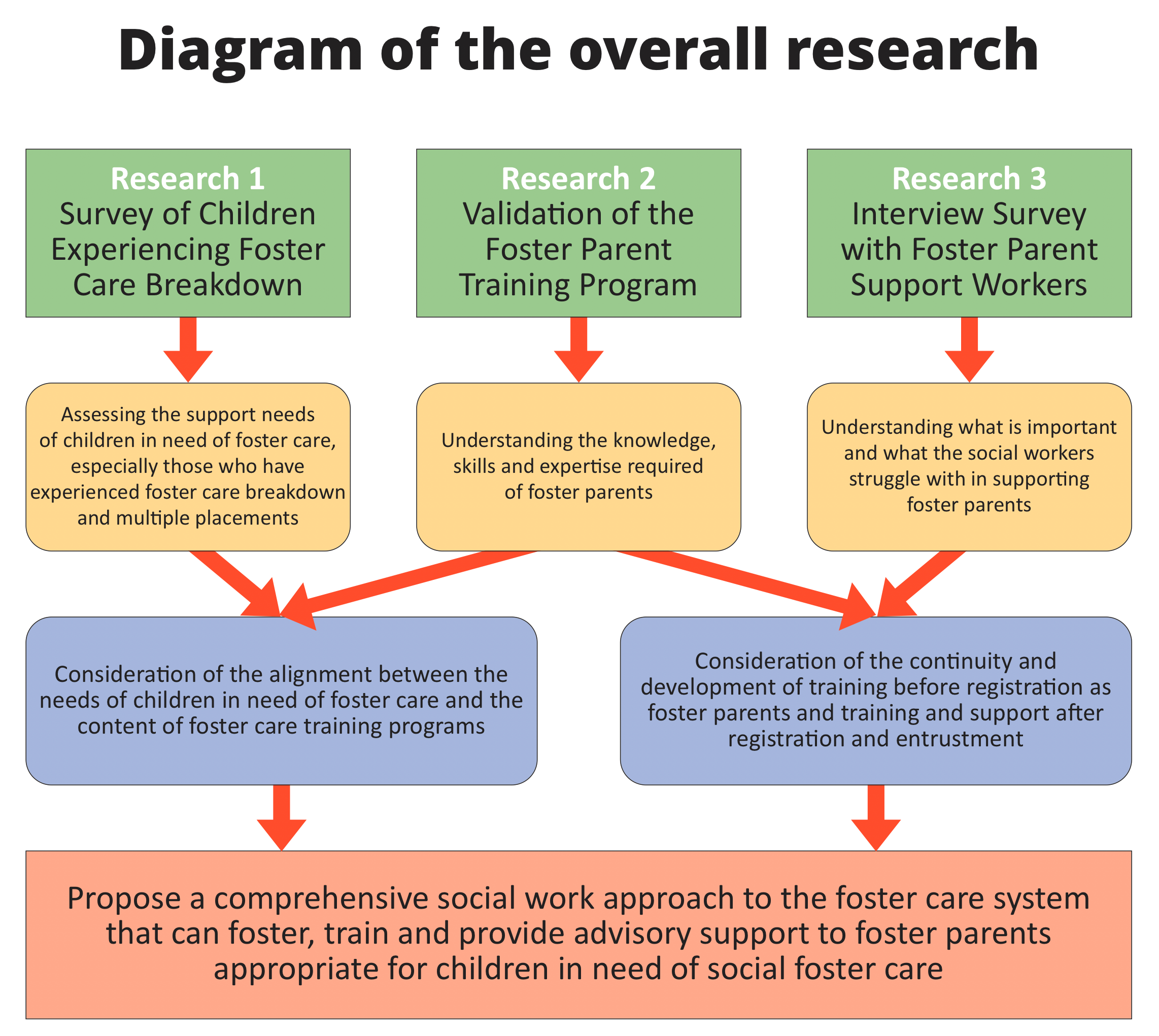

The purpose of my study

Based on my awareness of the above issues, I am currently conducting a research project intending to clarify the following four things.

1) Support the needs of children who need foster care.

2) Qualities and conditions of foster parents who can meet the support needs of children.

3) Training programme for foster parents who are capable of raising foster children appropriately.

4) Comprehensive social work for foster carers to support stable foster care.

Research methods

I am currently conducting the following four surveys.

1) A survey on the support needs of children who have experienced a change of placement to an institution in Japan due to the breakdown of foster care.

In FY2019, I conducted a fact-finding survey of 107 children who were changed to institutional care due to foster care breakdown in Japan (ACEs, SDQ, age, gender, pathway, etc.)

The results of the study revealed that children who had experienced foster care breakdown had much higher scores on both the ACEs and the SDQ than children who had not and that they had multiple serious behavioural and emotional problems. At this stage, it is not possible to determine causality as to whether these problems began before the children were placed in foster care, or whether they arose after the children were placed in foster care or as a result of their experience of poor foster care. One thing that can be said, however, is that the care needs of children who experience foster care problems and are transferred to institutions are very high, and institutions need to provide specialised care and treatment.

2) A comparative study between Japan and Scotland on the support needs of children who have experienced multiple changes of placement due to foster care breakdown.

Using the framework of the above survey, I would like to conduct a comparative study with children in Scotland who have experienced foster care breakdown and clarify the support needs of children who have experienced foster care breakdown.

In Scotland, children under the age of 13 are not placed in institutions rather than foster care, so I plan to exclude children under the age of 13 from the sample for the Japanese survey and compare the results between the two. At this stage, I know that looked-after children in Scotland experience more changes in placement than children in Japan. Unsurprisingly, children who change placements more frequently are more severely damaged. I believe that I can grasp some significant suggestions for Japan from the support needs of children who have experienced a change of placement in Scotland and the way residential care is provided in Scotland.

3) Review of the foster parent training program in Scotland

There are several foster care training programmes in Scotland, past and present. For example, “Skills to foster” and “Head, Heart, Hands Project” are examples of such programs. There are also several private foster parent support organisations in Scotland, each of which is believed to provide original foster parent support programmes.

At present, there are very few private foster parent support organisations in Japan, and public organisations are currently playing the caring roles. However, the Japanese government is planning to establish private fostering agencies in each municipality and to develop a support system for foster parents in each region.

Therefore, I would like to obtain hints from the Scottish practice to establish a comprehensive foster parent support system in each region, including recruitment, training, and visit support in Japan.

4) Interviews with foster care social workers & qualitative analysis

I am planning to elicit and qualitatively analyse what foster care support workers value in their practice and exploring the components of foster care social work in Scotland.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.

![Europe’s housing crisis: A fundamental social right under pressure Run-down appartment building in southeast Europe set before a moody evening sky. High dynamic range photo. Please see my related collections... [url=search/lightbox/7431206][img]http://i161.photobucket.com/albums/t218/dave9296/Lightbox_Vetta.jpg[/img][/url]](https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/iStock-108309610-218x150.jpg)