Dr. Karen McAuliffe, PI on the European Research Council funded project ‘Law and Language at the European Court of Justice’, discusses her theory of linguistic cultural compromise in EU law

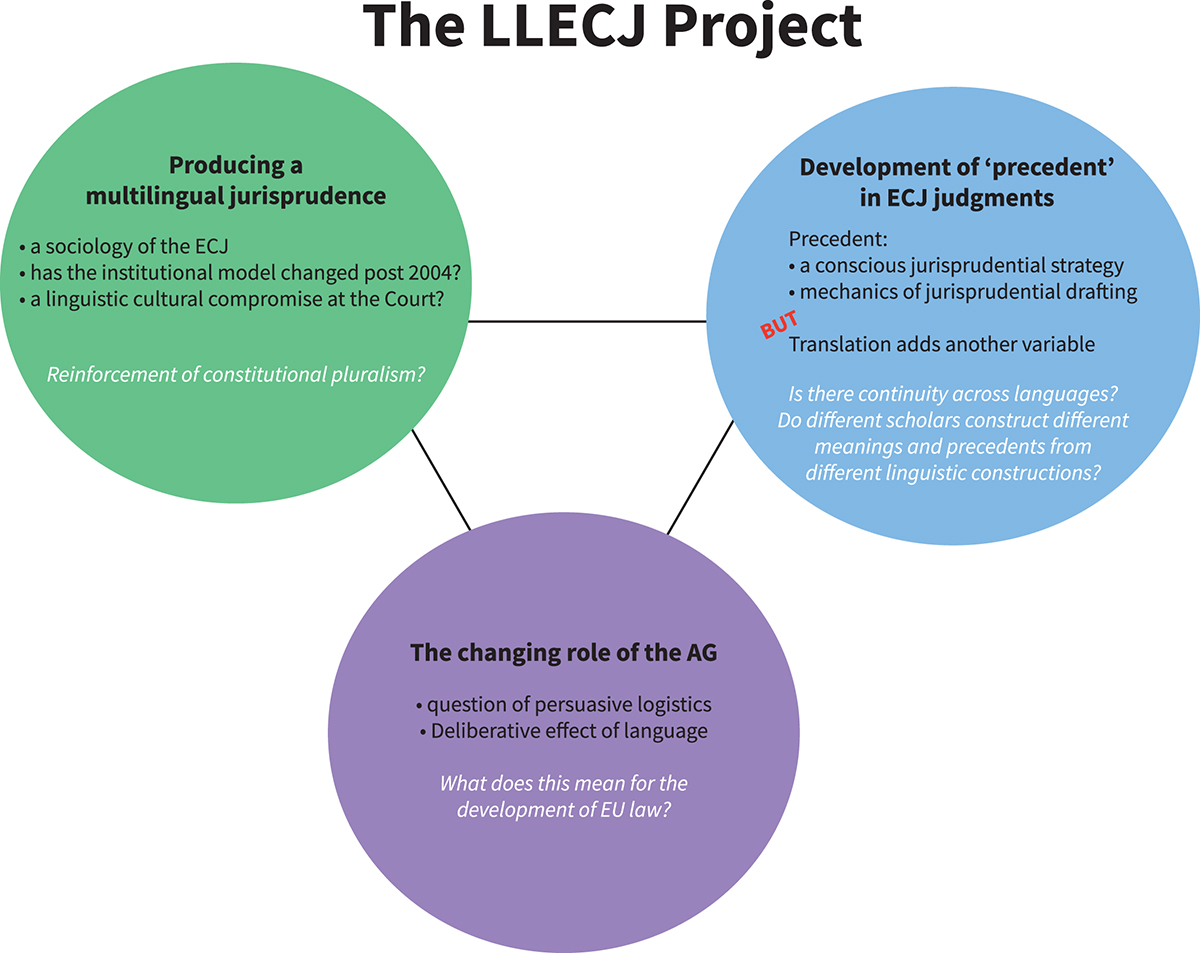

This article is the second in a five-part series focusing on the ERC-funded project ‘Law and Language at the European Court of Justice’ (the LLECJ project) – you can read the first article here. The LLECJ project is divided into three distinct yet interrelated sub-projects (see Figure 1), the first of which seeks to investigate the limitations of a multilingual legal system, by shining a light on processes and institutional culture within the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The research questions investigated in this sub-project included:

1. To what extent do language(s) and culture(s) affect the workings of the CJEU and the ‘output’ of that court (i.e. its jurisprudence)?

2. Can the judgments of the CJEU be considered ‘hybrid texts’? What might that mean for their application/implementation throughout European Union (EU) member states?

3. Has the reshaping of institutional norms at the CJEU since the ‘mega-enlargement’ of 2004 impacted on the ‘output’ of that court?

To investigate those research questions, an interdisciplinary mixed-methods approach was taken. First, systematic literature reviews were carried out, focusing on the relationship between law, language, culture and translation in international organisations and the notion of hybridity across disciplines. Those literature reviews informed the research design for in-depth interviews with various actors at the CJEU as well as (corpus) linguistic analysis of CJEU judgments.

Analysis of the various data collected has demonstrated that the multilingual jurisprudence produced by the CJEU is necessarily shaped by the dynamics within that institution and by the ‘cultural compromises’ at play in the production process. The resultant texts, which make up that jurisprudence, are hybrid in nature, consisting of a blend of cultural and linguistic patterns, constrained by a rigid formalistic drafting style and put through many permutations of translation. They are, as a result, inherently approximate.

On the one hand, that approximation can lead to discrepancies between language versions of CJEU case law and thus jeopardise the uniform application of EU law. On the other hand, that approximation and hybridity define EU law as a distinct, supranational legal order. In the context of the LLECJ project, we build on scholarship on ‘cultural compromises’ in EU institutions first set out by Marc Abélès and Irène Bellier.1 Going beyond their work, we put forward a theory of ‘linguistic cultural compromises’ in EU law. There are two main elements to such linguistic cultural compromises:

(a) The linguistic-cultural compromise by which the case law of the CJEU is created: the collegiate judgments of the CJEU are, by their very nature, compromise documents and, because the deliberations are secret, it is, in theory, impossible for anyone other than the judges involved to know where compromises lie in a text. This has implications both for the subsequent translation of such judgments and also for the drafting of future judgments. Furthermore, the case law of the CJEU is shaped by the language in which it is drafted – i.e. French. However, because French is rarely the mother tongue of those drafting that case law, there is a tendency to repeat expressions and to ‘cut and paste’ from previous case law or source documents. Together with the difficulties of manipulating a language that is not one’s own, the result is often a stilted and awkward text. These, and other, factors have led to the development of a ‘Court French’ which necessarily shapes the case law produced and has implications for its development.

(b) The linguistic cultural compromise by which that law is filtered out to the wider EU through translation: The case law of the CJEU is ‘filtered out’ through linguistic cultural compromises involved in translation. Translation itself is a ‘linguistic cultural compromise’ and all translation, including legal translation, involves an element of approximation. Lawyer-linguists are responsible for translation at the CJEU. As well as dealing with the classic problems of translation such as ambiguity, translation of ‘untranslatable’ legal concepts, the effects of translated legal texts etc., lawyer-linguists’ role perceptions also affect translation at the CJEU. The lawyer-linguists work at the interface of law and language, dealing with the relationship between those two concepts on a daily basis. The necessary compromise resulting from the struggle to reconcile the notions of ‘law’ and ‘translation’ is reflected in the process whereby CJEU case law is ‘filtered’ out to the wider EU.

The research carried out in the context of the LLECJ project makes explicit that which the majority of actors at the CJEU, and indeed at an EU level in general, already know – that EU law is a multicultural, multilingual construct which functions by way of approximation, and that its continued effectiveness is, in fact, dependent upon its hybrid nature.

This article series will continue in the next issue, which will focus on the development of ‘linguistic precedent’ in CJEU judgments. For more information on the LLECJ Project see www.llecj.karenmcauliffe.com

References

1 Cf Abélès (2004) “Identity and Borders: An Anthropological Approach to EU Insitutions”, Twenty-first Century Papers: Online Working Papers from the Center for 21st Century Studies 2; Bellier (2002) “European Identity, Institutions and Language in the Context of the Enlargement” Journal of Language and Politics 1, 85-114; Bellier (2000) “A Europeanized Elite? An Anthropology of European Commission Officials” Yearbook of European Studies 14, 135-156.

Dr. Karen McAuliffe

Reader in Law and Birmingham Fellow

The University of Birmingham

Tel: +44 (0)121 414 7269

k.mcauliffe@bham.ac.uk

www.karenmcauliffe.com

www.twitter.com/dr_KMcA

*Please note: This is a commercial profile

![Europe’s housing crisis: A fundamental social right under pressure Run-down appartment building in southeast Europe set before a moody evening sky. High dynamic range photo. Please see my related collections... [url=search/lightbox/7431206][img]http://i161.photobucket.com/albums/t218/dave9296/Lightbox_Vetta.jpg[/img][/url]](https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/iStock-108309610-218x150.jpg)