Andrew Nunn, Professor of Epidemiology, Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, describes the first phase 3 trial of a shortened treatment for MDR-TB

The 1970s and 80s saw a revolution in the treatment of tuberculosis worldwide. Following the discovery of rifampicin, laboratory studies suggested it might enable substantial shortening of treatment duration, which was 18 months or more and often associated with problems of poor adherence.

Trials conducted by the British Medical Research Council (MRC) demonstrated that regimens based on six months of rifampicin and Isoniazid were as successful as the longer 18-month regimens and as a consequence a six-month regimen was adopted worldwide; it remains the WHO recommended first-line treatment for the drug-sensitive disease.

Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB)

Primary resistance to rifampicin, which is resistance in patients who had not received the drug previously, was initially very rare, but it was noted that patients infected with rifampicin-resistant strains were unlikely to respond well to the new regimen, even when it included two or three additional drugs. Rifampicin resistance was often associated with resistance to isoniazid, another key drug in the regimen; resistance to both drugs came to be known as multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB).

In 1996, WHO reported outbreaks of MDR-TB in different regions of the world which they attributed to ‘inappropriate use of essential antituberculosis drugs’ (1), which included poor adherence to treatment, resulting in acquired resistance to rifampicin which would then be transmitted as the primary resistance to previously uninfected persons.

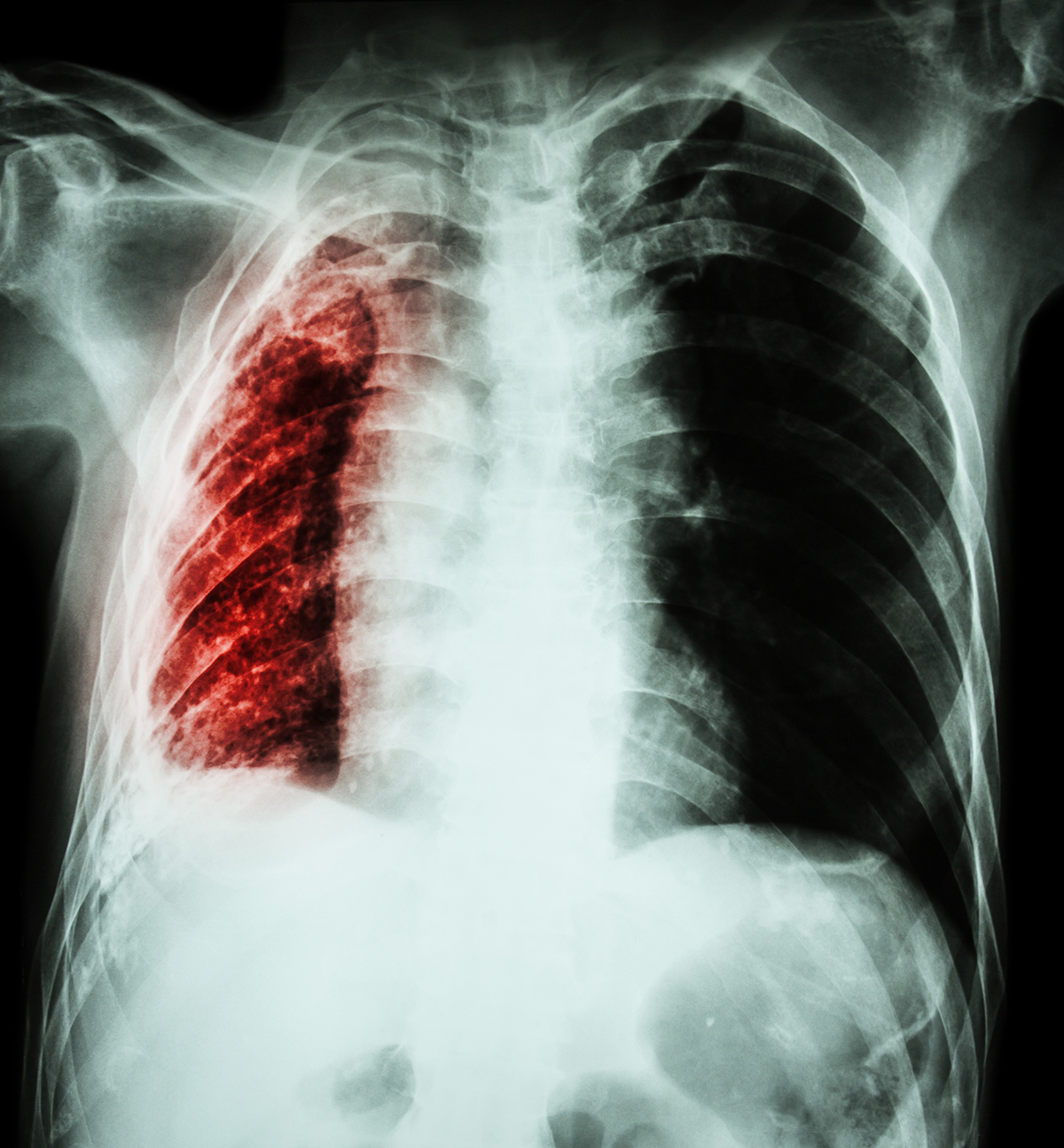

In countries with good laboratory facilities, individualised treatment strategies to treat MDR-TB were recommended, however, such resources were not available in many low-income settings and during 1995, Van Deun and colleagues initiated the first of a series of cohort studies in Bangladesh using standardised regimens.

The project targeted maximum effectiveness, minimising the use of drugs with a poor toxicity profile and focussing on reducing the risk of additional acquired resistance. The results in the sixth cohort, which was given for nine months in contrast to the regimens of 20 months or more recommended at the time, were particularly encouraging. Out of 206 patients enrolled, 87.9% had a satisfactory outcome by the WHO definition and did not relapse subsequently.

The response to the publication of these results was mixed. Some advocated the immediate introduction of this regimen more widely, while others were more circumspect, pointing out it was an uncontrolled study conducted in one country which could not be said to be typical of other settings, not least because of the absence of HIV-infected patients.

Optimal use of existing drugs for MDR-TB treatment

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) considered it important to establish whether this regimen was as effective as the WHO recommended treatment and invited proposals to conduct a multi-site clinical trial to determine the optimal use of existing drugs for MDR-TB treatment. The International Union Against TB and Lung Disease successfully responded to the request and invited the MRC Clinical Trials Unit and other partners to collaborate in the design and conduct of the study.

The primary aim of the STREAM trial was to assess whether the nine-month regimen developed in Bangladesh was non-inferior to (not much worse than) the 2011 WHO-recommended regimen for MDR-TB. The regimen was the same as was used in Bangladesh with one exception, moxifloxacin was used in place of gatifloxacin because the latter drug was no longer produced to Good Manufacturing Practice.

The two core drugs in the regimen were considered to be moxifloxacin and the injectable kanamycin; patients whose organisms were resistant to either of these drugs on the rapid test were ineligible for the study. Kanamycin was only given during the 16-week intensive phase unless there was evidence of delayed conversion to microscopy negativity in which case it could be extended to 20 or 24 weeks. The control regimen was the WHO regimen as implemented locally in participating countries.

The primary endpoint of the study was the status of the participants at week 132 after randomisation; an unfavourable outcome included not only bacteriological failure or relapse, but death from any cause and changes or extension of treatment for adverse events, in particular, failure to tolerate the allocated regimen. Participants were randomised in the ratio of 2:1 for the nine-month (Short) regimen compared to the WHO (Long) regimen. A total of 424 participants enrolled from Ethiopia, Mongolia, South Africa and Vietnam.

STREAM study results

Follow-up was excellent and the outcomes of the two regimens were very similar, 79.8% of participants receiving the Long regimen and 78.8% of those receiving the Short regimen had a favourable outcome. The difference of 1.0% (95% Confidence Interval -7.5%, 9.5%) was within the pre-specified 10% margin of non-inferiority. (1) Participants receiving the Long regimen did better than had been expected, this was probably due to intensive supervision throughout the trial.

Results in the subgroup of HIV-coinfected patients were less good in both regimens, but there was no evidence to suggest that those receiving the Short regimen did less well than those receiving the Long regimen. Disappointingly, shorter treatment did not result in a reduction in the frequency of adverse reactions.

Bedaquiline

Even before the results were known, USAID invited the STREAM trial investigators to consider whether the trial could be expanded to evaluate Bedaquiline, a new drug that had only recently received provisional registration, the first new TB drug for almost 50 years. The trial team proposed evaluation of bedaquiline-containing experimental regimens that replaced kanamycin, the injectable which could cause deafness or reduced its duration.

Janssen Pharmaceuticals, who developed bedaquiline, expressed an interest in collaborating on Stage 2; this enabled the investigators to include two experimental regimens – an all-oral nine-month regimen and a six-month regimen. Georgia, India, Moldova and Uganda are also participating in this stage; a total of 588 participants enrolled, and results are expected later this year.

Looking ahead

STREAM was the first multi-centre trial to assess treatment regimens for MDR-TB, other trials are now underway and the expectation is that in the not too distant future, highly effective shorter treatments will become available.

References

- http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63465/WHO_TB_96.210_(Rev.1).pdf;jsessionid=177C56E7F21F118BCDE0186232C2996C?sequence=1

- Nunn AJ, Phillips PP, Meredith SK, et al. A trial of a shorter regimen for rifampin-resistant tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380 (13):1201-1213.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.