Wendy Harrison, CEO of the SCI Foundation, outlines the importance of putting parasitic infections on the map, with a particular focus on schistosomiasis

30th of January 2023 commemorates World Neglected Tropical diseases day. It is a day to raise awareness of diseases that affect over 1 billion people in some of the most marginalised communities. It is also an opportunity to take stock of the efforts made by governments, donors and NGOs towards eliminating these diseases and parasitic infections.

For me, it is a day to put parasitic infections on the map. Malaria is one of the deadliest and best well-known among the parasitic diseases. But other less well-known diseases impact millions of people but are much less well known, for example, schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia or snail fever.

What is schistosomiasis?

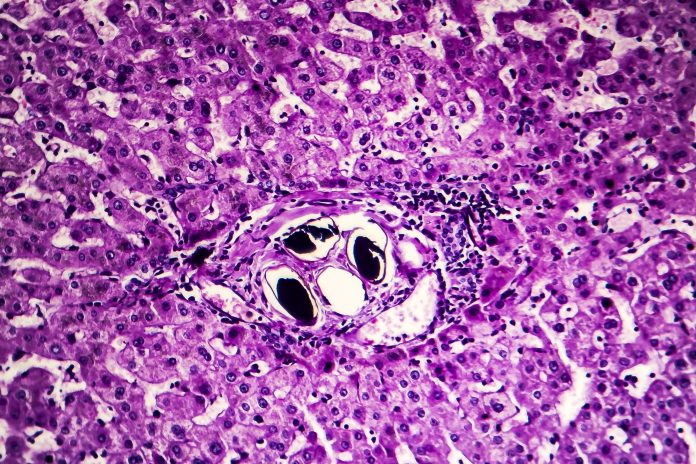

Schistosomiasis is a disease caused by parasites known as schistosomes. These parasites are commonly found in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and Asia.

The disease affects over 240 million people globally and causes an estimated 200,000 deaths yearly. A person gets infected when the parasite’s larvae penetrate a person’s skin during contact with infested water, often through fishing, swimming, bathing and washing clothes.

Schistosomiasis is transmitted when eggs are excreted through the faeces or urine of infected individuals in or near surface water where the intermediate snail hosts are present. The parasite replicates in the snail are releasing infective larvae into the water.

In areas where communities have poor access to water and sanitation, the parasitic infection cycle inevitably continues as infected people use water sources to urinate and defecate, releasing the eggs into the water.

How is peoples’ health affected by these parasitic infections?

The impact of schistosomiasis is greatest in young and school-aged children, who present with symptoms such as anaemia, stunted growth and abdominal cramps. If the disease is left untreated, it can lead to more serious complications, depending on the species involved. Urogenital symptoms (caused by S. haematobium) include bladder pathology, including cancers and genital schistosomiasis, increasing the risk of HIV infection. Intestinal schistosomiasis (caused by S. mansoni and all other species) can lead to damage to the liver and spleen.

Drug treatments for schistosomiasis

The current approach to controlling schistosomiasis relies on mass drug administration, or MDA, (covering entire populations in which prevalence is higher than 10%) using Praziquantel (PZQ). This cost-effective drug can kill adult worms within infected humans.

Historically, we have worked with ministries of health to deliver treatments to school-aged children. These treatment programmes are essential to SCH control, but PZQ cannot kill immature worms or prevent reinfection. Therefore, in many settings, mathematical modelling data suggests that treatment of school-aged children alone will not lead to the elimination of schistosomiasis. In the absence of reaching elimination, resources would need to be invested every year on an ongoing basis to protect children’s health. Drug uptake may decrease over time due to fears over side effects, treatment ‘fatigue’ and absence during drug distribution activities. Control programmes rely on donated drugs, which, although makes the intervention very cost-effective in the short term, may lead to questions around longer-term sustainability.

Control and elimination of schistosomiasis

There is growing global recognition that sustained control and elimination of schistosomiasis requires interventions to reduce environmental exposure and transmission, alongside continued MDA. Sustained reductions in prevalence through environmental and behavioural measures could also make MDA more effective by reducing the risk of exposure to parasitic infections.

Although improvements in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities and water contact behaviours are acknowledged as crucial to breaking or reducing SCH transmission, the specific interventions necessary for every context, and the best approaches to their sustainability, are not routinely established. In endemic communities, therefore, WASH services are often absent or badly adapted to community health needs and, specifically, fail to promote disease prevention.

In addition, current approaches to inform communities on the risks of schistosomiasis, such as open defecation or contact with snail-infested surface water (“community education”) often fail to recognise the cultural, wellbeing and economic reasons underpinning contact with contaminated surface water and poor access to sanitation, making them largely ineffective at changing behaviours.

Finally, a lack of coordination between WASH, Environment and Health authorities means that interventions in one area fail to complement or actively undermine, interventions in another. For example, behaviour change messaging on the health risks of open defecation may be undermined by the installation of WASH infrastructure far from where economic activities are carried out and where suitable quality latrines are unavailable.

Working across different sectors, including environmental and animal health, and being responsive to the specific contexts and needs of national programmes, also supports the further development and strengthening of existing systems. Resilience national systems offer the potential for more sustainable disease control and elimination efforts that also protect populations against other existing and emerging health threats.

As World NTD Day approaches, I reflect on the crucial need for a viable intervention package for schistosomiasis control and elimination, comprising community-driven and context-specific interventions that can inform the design of sustainable WASH and behaviour change interventions and promote collaboration across sectors.

By having communities at the heart of the design of these activities, I am hopeful that the elimination of schistosomiasis one day will become a reality.

WHO: Neglected tropical diseases

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are 17 bacterial, parasitic and viral diseases that only or principally happen in tropical regions, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Africa notes. “They are often termed ‘neglected’ as the people who are most affected are the poorest populations living in rural areas, urban slums and conflict zones,” WHO adds. (1)

In June 2022, the WHO, with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, heralded to set up a mentorship programme for African women working in NTDs. “Focused specifically on African women living in African countries, the programme aims to help them overcome barriers to realizing their potential and become leaders and champions of neglected tropical disease elimination at home and internationally,” Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, said. (2)

Schistosomiasis is one of the NTDs. (3) WHO Africa notes that schistosomiasis is a disease of poverty that results in chronic ill-health, but how does infection occur? WHO answers: “Infection is acquired when people come into contact with fresh water infested with the larval forms (cercariae) of parasitic blood flukes, known as schistosomes.” Did you know that schistosomiasis impacts nearly 240 million individuals globally? However, the WHO strategy on using anthelminthic drugs means that schistosomiasis is controlled in marginalized and poor communities. (4)

References

- https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases

- https://www.afro.who.int/news/neglected-tropical-disease-mentorship-launched-honour-dr-mwele-malecela

- https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/index.html#:~:text=Schistosomiasis%20is%20considered%20one%20of,the%20snail%20into%20the%20water.

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/schistosomiasis#tab=tab_1

Further reading

https://www.afro.who.int/news/why-do-neglected-tropical-diseases-suffer-low-priority