Open Access Government speaks with Sigrid Suetens, a Professor in the Department of Economics at Tilburg University, about her research monitoring taste-based discrimination in Europe

Since obtaining a PhD in applied economics at the University of Antwerp in 2005, Sigrid Suetens’ research focuses on understanding behaviour in environments where there is a tension between opportunism and cooperation, and recently also on ethnic discrimination. She has published in highly ranked journals in economics (for example, Review of Economic Studies, Journal of the European Economic Association, Economic Journal) as well as in multidisciplinary journals (Management Science, Evolution and Human Behaviour, Scientific Reports).

Can you tell us a bit about your research interests and what your work means to you?

“I am very much interested in understanding cooperation among people. Under which conditions are they willing to put their own interests aside and contribute to the group? To which extent do they act strategically to get the most out of a situation? How important are emotions? As a method I often use economic experiments. In such experiment’s, participants are confronted with simple decisions that represent key features of real-life decisions; importantly, there is something (typically money) at stake.

I started to be interested in ethnic discrimination by seeing that some (minority) friends experienced it first-hand. When looking up the academic literature, I quickly realised that there were not that many studies that addressed taste-based discrimination, or at least not in a way that allowed making general conclusions. This is how the Diverse-Expecon project started.”

As the Principal Investigator of the Diverse-Expecon project, tell us about the project’s objectives and aims?

“The aim of this project is to study whether and how tastes are important to understand discrimination. A large part of the work involves giving people the opportunity to make choices that have real financial consequences, then assessing their responses. For example, in part of the experiments, we confront large samples of the majority with a decision-making setting were there is not really any behavioural uncertainty. This allows us to investigate whether respondents treat people from an ethnic minority background any differently. In these experiments, people have to decide how amounts of money are allocated between oneself and another person. The trade-off comes down to for example a choice between the two parties getting an equal amount, which would still be reasonably high, or the decision-maker getting a very high amount and the other person getting a very low amount. In some cases, this other person has a majority background and in other cases (s)he is part of an ethnic minority.

A first objective is figuring out the conditions under which people discriminate minorities; for example, is it because they dislike having less, or because they really want to be better off, or because they just care less for the wellbeing of ethnic minorities?

A second objective is to understand fairness ideals when it comes to the redistribution of money. Current theoretical research on distributive justice stipulates that fairness ideals should not depend on factors for which individuals cannot be held responsible, such as ethnic background. However, fairness ideals sometimes allow room for interpretation and can justify discriminative behaviour. We study whether income inequalities are compensated for to the same extent between majority and minority than among the majority, and whether the answer depends on the source of inequality (responsibility versus luck).

A third objective consists of studying the effect of exposure to ethnic minorities and personal contact on discrimination and attitudes towards them.”

What is the difference between statistical and taste-based discrimination, and why is it important to recognise the difference between the two?

“Statistical discrimination refers to discrimination in a context with behavioural uncertainty. In such a context, individuals do not know how the person with whom they interact will behave. They may, therefore, rely on information about the group to which the person belongs to form beliefs about the person’s behaviour. This may lead to discrimination on the basis of observable features of the group, which are thought to correlate with the expected behaviour of the other person. For example, an employer who is informed about unemployment rates among ethnic minorities may come to believe that minorities are less productive than someone who is part of the native majority and may, therefore, be reluctant to hire someone with a minority background.

In the case of taste-based discrimination, individuals discriminate even if there is no behavioural uncertainty. That is, they suffer a disutility when interacting with specific others, for example, people with a different ethnicity. Consider the hypothetical case of an employer who needs to make a hiring decision and is faced with two employees, one majority and one minority, who have the exact same CV, the same expected future productivity, the same expected team spirit etc. If the employer would still choose to hire the majority person, then this means (s)he has a taste to do so. Taste-based discrimination refers to discrimination that is due to tastes of people, or what is referred to as preferences in economics.

For policymakers, it is important to recognise the difference between statistical and taste-based discrimination. Both types of discrimination require different policies. Policies aimed at overcoming statistical discrimination are directed at the provision of accurate information about ethnic minorities to decision-makers. In the example provided above, statistical discrimination can be overcome if the employer has as much accurate information as possible about the specific employees involved (e.g. detailed CV, references, etc.). Policies aimed at overcoming taste-based-discrimination, instead, should deal with influencing preferences of people, and most likely require something more than the provision of information.”

In what way does taste-based discrimination negatively impact people of colour, and how can we eliminate it to be actively anti-racist in the workplace?

“The consequence can be that people with a minority background are less frequently offered jobs than people with a majority background, that they earn a lower wage for the same type of work, that they are punished harsher for the same crime, that their children are not invited to birthday parties, etc. A range of academic papers has shown that positive contact is effective in reducing racism and improving attitudes towards ethnic minorities. Positive contact refers to personal long-lasting contact between majority and minority, sharing a common goal, having empathy for one another.”

To what extent does the Dutch population’s trustworthiness depend on the ethnicity of their interaction partner?

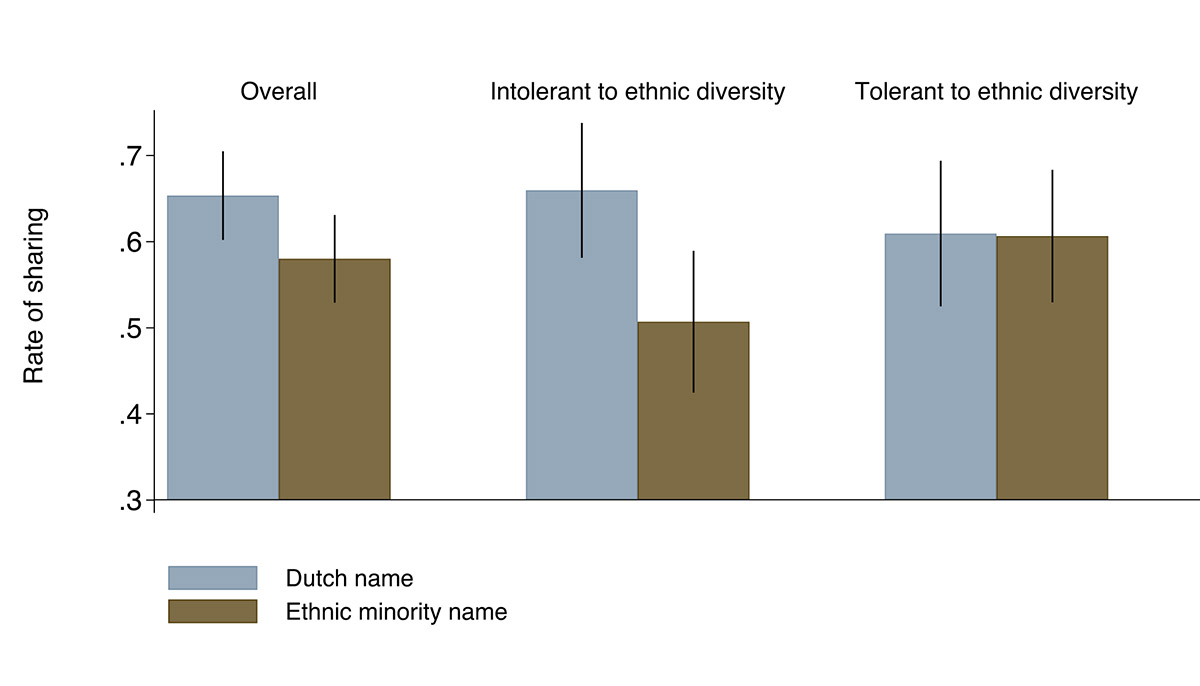

“In the study you are referring to, which was conducted with my colleague Elena Cettolin, there was some real money at stake for participants. Native Dutch trustees were faced with a real but anonymous partner and were shown the first name of this person. Half of the trustees had a partner with a native Dutch name and the other half had a partner with an obvious minority name. Trustees were carefully explained that their partner had made a risky choice to invest money in them, they had trusted them, and that by investing the money, the total pie of money increased. Trustees could then either take most of the pie and leave a bit for the partner or share the pie with the partner. We found that trustees were less likely to share with partners with a minority background than with a majority partner.

The study also found that trustees who tend to think negatively about immigrants and ethnic diversity in society were the ones who discriminated. In contrast, trustees with a positive attitude did not condition their decision on the ethnic identity of the trustor. In the worst possible case for minorities the likelihood that their trust actually paid off was more than 20% lower than for majority. The figure above shows the rate of sharing as a function of the background of the interaction partner, and as a function of the attitude to ethnic diversity.”

How can this single act of discrimination signify wider problems in attitudes towards immigrants?

“Given that the behavioural results and the self-reported attitudes to ethnic diversity are well-aligned, we do believe that the single act of discrimination signifies a wider problem. Although we did everything we could to avoid it, it is possible that at least some participants may have been aware that the study was on ethnic discrimination. Given that people typically want to hide discriminatory behaviour, one could take the level of taste-based discrimination that we find as a lower bound.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

![Europe’s housing crisis: A fundamental social right under pressure Run-down appartment building in southeast Europe set before a moody evening sky. High dynamic range photo. Please see my related collections... [url=search/lightbox/7431206][img]http://i161.photobucket.com/albums/t218/dave9296/Lightbox_Vetta.jpg[/img][/url]](https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/iStock-108309610-218x150.jpg)