Researchers have identified why certain cells in the body, known as Th17 cells can go rogue and promote the onset of MS

The Australian National University (ANU) researchers have published a new study that explores how certain cells designed to help to body can have nasty side-effects on the body’s immune system causing the onset of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS).

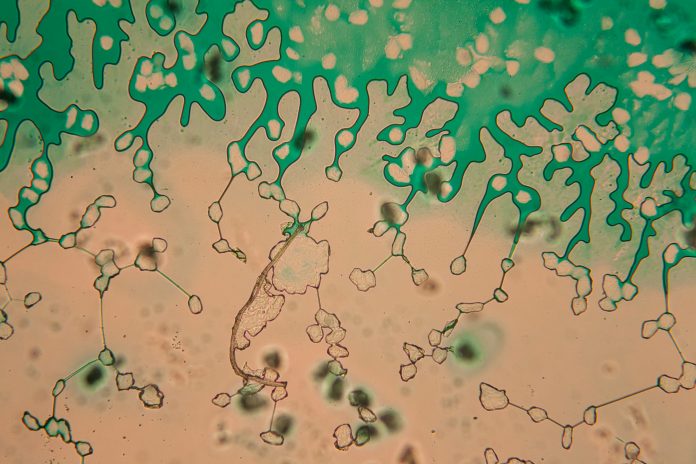

By discovered a previously unknown and nasty side effect of a bacteria-fighting weapon in the immune system’s arsenal called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), scientists finally understand that NETs are responsible for directly enhancing the production of harmful Th17 cells. This discovery is opening doors to the development of future therapies that can hinder the harmful NET-Th17 interact that is causing so much harm – therefore improve treatments for MS and several other autoimmune diseases.

“This discovery is significant as it provides a novel therapeutic target to disrupt these harmful inflammatory responses,” lead author Dr Alicia Wilson, from the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz in Germany, said.

Th17s and NETs

Defending the body against bacterial and fungal infections is the norm for Th17’s when they’re behaving normally, however when over-activated they can cause some serious damage and inflammation. When aggressive, Th17 cells can be responsible for promoting autoimmune diseases like MS.

NETs capture and kill nasty bacteria, they’re designed to protect the body from infection however it has become clear that they have the ability to manipulate Th17 cells making them stronger and more dangerous. “We found that the NETs cause Th17 cells to become more powerful, which enhances their detrimental effects,” senior author Associate Professor Anne Bruestle, from the ANU Department of Immunology and Infectious Disease, said.

Through this research, scientists hope to gain an understanding into how NETs turn Th17 cells from friend to foe – therefore enabling them to create more targeted therapies to inhibit the bad effects of NETs.

Associate Professor Bruestle and their team of researchers believe a drug originally designed to treat sepsis could be used to target the bad Th17 cells – “Because we see in both mice and humans that a group of proteins in NETs called histones can activate Th17 cells and cause them to become harmful, it makes sense that our histone-neutralising drug, mCBS, which was developed to treat sepsis, may also be able to inhibit the undesirable effects of NETs which are linked to driving MS,” Professor Parish said.

Associate Professor Bruestle said: “While we cannot prevent autoimmune diseases such as MS, thanks to these types of therapies we hope to treat the condition and make it more manageable for people living with MS.”