David Tyrrell, TeleTracking, explains why every minute matters when it comes to the bed availability crisis within the NHS

As Providers across the National Health Service focus upon elective recovery in a post-pandemic environment, general and acute bed capacity has never been more pressurised. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has raised concerns that there is a national deficit of between 4,988 and 15,788 general and acute beds(1) to safely manage expected demand through the coming winter, assuming demand does not exceed 2018/19 levels. The BMA states that at least 3,000 additional beds are required to allow Trusts to avoid opening escalation beds outside of the winter period(2), further commenting that in May 2019, nine out of ten Trusts had open escalation beds in use.

Further pressure on bed capacity is coming from the longest waiting lists for elective surgery ever recorded, with 4.7 million patients waiting for treatment in February 2021, 387,885(3) of those waiting for more than 52 weeks. The NHS has made £1 Billion available in additional funding to secure additional elective activity(4). Even without taking into account the current long-term crisis in staffing (the King’s Fund has reported(5) a shortage of 84,000 FTE nationally), the NHS is facing an unprecedented range of challenges. Minutes have never mattered more than in the present perfect storm.

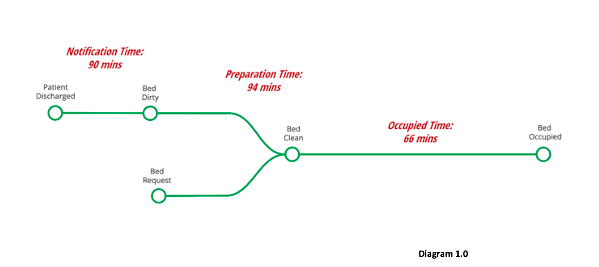

A recent analysis of acute sector performance conducted by TeleTracking has highlighted the potential to release the equivalent of nearly 7,000 beds per day across the NHS in England. This analysis took into account the often-ignored transactional delays to declare an empty bed, prepare the bed for the next patient and the time taken to move the incoming patient into the waiting bed. Declaration, preparation and occupation times add up to an unmeasured amount of ‘lost’ bed time, which in our experience averages at least 250 minutes per admission. TeleTracking clients who do measure ‘lost’ bed time with our technology and analytical tools, aim to reduce this 250 minutes to 90 minutes per admission. By applying this approach to all acute providers in England, we estimated that in the past year there were on average 6,911 beds ‘lost’ to the system.

Given the current extraordinary pressures on inpatient beds, the opportunity to release roughly the equivalent capacity of 276 inpatient wards, 11 mid-sized hospitals, or indeed the combined bed capacity of North West London and South East London, every day, is an opportunity that cannot, and indeed should not, be overlooked.

The data points captured in diagram 1.0 above constitute the ‘lost’ bed time that we typically measure in new NHS clients.

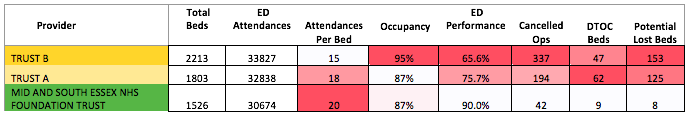

We believe, and our experience has reinforced the fact, that minutes do, in fact, matter. They matter a great deal. For illustration, we have compared the performance of the three busiest English providers in May 2021 as calculated by ED attendance numbers. The relative performance is shown in Table 1.0 below(6).

The third column, attendances per bed, is a proxy measure we used to identify how ‘hot’ each site was during the month, by dividing the reported number of ED attendances for the month by the number of G&A beds declared for the same period.

By this measure, Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust (MSE) was ‘busier’ (with 30,674 attendances and 1,526 G&A beds) than both Trust A with 32,838 attendances and 1,803 beds and Trust B who had 33,827 attendances with 2,213 G&A beds.

Despite having 20 attendances per bed, 2 more per bed than Trust A and 5 more than Trust B, MSE were able to significantly outperform their larger peers on the National ED 4 hour target by recording performance for the month of 90%.

Trust A occupancy at 87% was the same as MSE, with Trust B struggling at 95% occupancy. High occupancy levels, resulting in a lack of available beds can have a very negative impact on patient safety and the patient experience.

“A lack of available beds can have widespread consequences in a health system. For example, it can increase delays in emergency departments, cause patients to be placed on clinically inappropriate wards and increase the rate of hospital-acquired infections, while pressure on staff to free up beds can pose a risk to patient safety. Bed availability is also closely linked to staffing, as beds cannot be safely filled without appropriate staffing levels.”(7)

High occupancy rates are often a symptom of poor patient flow, though, given the spike in ED attendances nationally post-pandemic, many Trusts are experiencing significant and unprecedented increases in both attendances and (anecdotally) conversion rates, pressurising occupancy. In such testing times, it is essential that Providers make the best use of all available resources, especially their bed base.

As per the old adage, “if you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it” is our considered view that by measuring the time between patient ‘A’ leaving a bed, and patient ‘B’ occupying the same bed, Providers can measure their lost bed time. The use of PAS/EPR data is useful, however, unless the patient record is updated in real-time (and it rarely is), there will be a time lag between the patient vacating their bed and the bed being ‘declared’ as being vacant and therefore available for occupancy. This is why we would strongly recommend that real-time use of PAS/EPR systems is mandated and managed closely. Once there is a reasonable level of confidence that this has been achieved, the data can be a useful proxy measure of ‘lost’ bed time, and Trust Leadership Teams can devise the most appropriate means to manage and reduce ‘lost’ bed time, thus making better use of funded, staffed inpatient beds.

Conclusion

The NHS, and the people who make up our incredible health service, have faced unprecedented and in some cases, overwhelming, pressures throughout the pandemic. The pandemic has also wrought havoc on the delivery of elective surgery programs, resulting, in many cases, in dangerous delays for planned care. What this data demonstrates, both before and during the pandemic, is that providers focusing on reducing ‘lost’ bed time are able to do more with less when compared to their peers.

Yes, minutes do matter and if waiting lists are going to be managed safely in the medium to longer-term, providers need to both measure and manage ‘lost’ bed time in order to make the most of the capacity available to them. We have identified nearly 7,000 ‘additional’ funded and staffed beds potentially available to the system, without requiring new buildings, staff or clinical equipment. If your elective recovery plan does not include a strategy to reduce ‘lost’ bed time, the question must be; why not?

References

(1)RCEM Explains: Hospital Beds – parliamentary briefing: www.rcem.ac’uk

(2)www.bma.org.uk September 2020: Bed occupancy in the NHS

This report highlights the use of extra escalation beds in the NHS outside of winter. Read more about our recommendation to increase core bed stock across the NHS.

(3)O’Dowd, Adrian, NHS waiting list hits 14 year record high of 4.7 million people BMJ 2021 ; 373 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n995 (Published 15 April 2021)

(4)NHS News – www.england.nhs.uk

(5)www.kingsfund.org.uk – NHS workforce: our position, 26th February 2021

(6)Data from NHS National dataset as per the list below – cancelled operations and DTOC data is from comparable pre-covid periods.

(7)www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk Hospital bed occupancy We analyse how NHS hospital bed occupancy has changed over time. 25/06/21