Looking at speech patterns throughout history, the processing of language is based on how frequently we hear sounds – which causes gradual language change

Researchers investigating the changes in speech patterns and sound during the Middle Ages develops what we know about how we process language, looking at what parts of the brain alter our language learning.

The processing capacities of our brains show us that throughout history, our language is constantly changing.

Over centuries, frequently occurring speech patterns become more frequent, this development is due to our brains perceiving, processing, and learning frequently, which thus develops prototypical sound patterns more easily than less frequent ones.

“This second generation of speakers transmits a slightly changed language to their own children.”

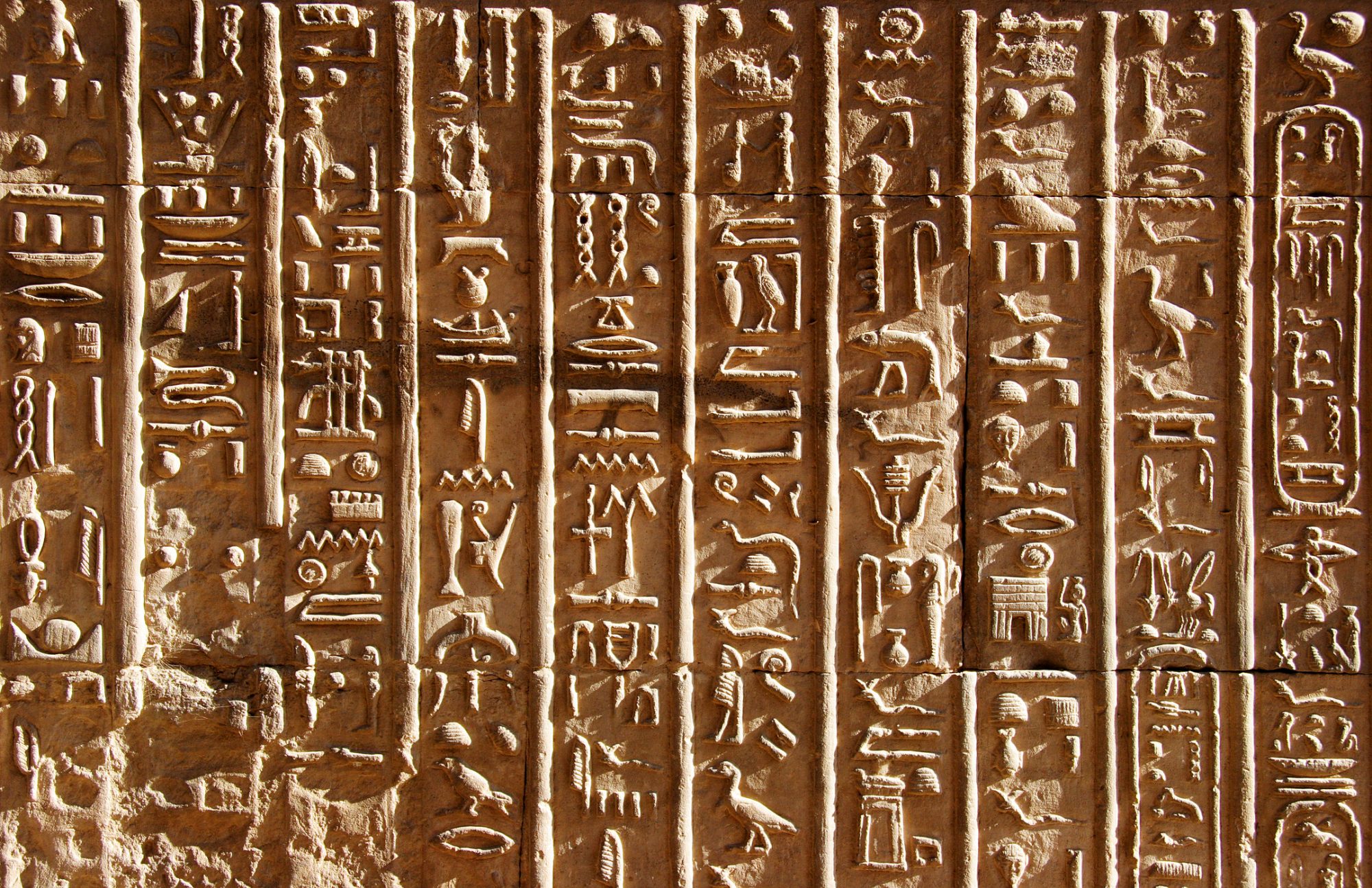

Languages from the past are very different from today’s languages

Researchers of the University of Vienna found that modern vocabulary and grammar, as well as speech sounds, as extremely different to languages of the past.

Researchers evaluated over 40,000 words from English texts from the Early Middle Ages. They determined their vowel lengths by using dictionaries or taking neighbouring sounds into account.

Counting the occurrence frequencies of words with long and short vowels, researchers found that most monosyllabic Middle English words had long vowels and only a minority had short vowels.

An example of their work on language adaptation can be seen studying the Early Middle Ages, where the English word ‘make’ was pronounced as “ma-ke” (with two syllables and a short “a” similar to the vowel in cut), whereas in the Late Middle Ages, it was pronounced as “maak” (with one syllable and a long “a” similar to the vowel in father).

Many Middle English words lost their second syllable and lengthened their vowel as it happened for the word make.

What was the reason for this lengthening of vowels in words that lost their second syllable?

Essentially, people prefer speech patterns that occur frequently.

Theresa Matzinger, from the Department of English at the University of Vienna, said: “This means that, when speakers pronounced monosyllabic words with a short vowel, those words sounded ‘strange’ and were not recognised clearly and quickly by listeners because they did not fit the prototypical sound patterns that listeners were used to.

“In contrast, words that fitted the prototypical sound patterns with a long vowel, could be processed by the brain more easily.”

The researchers describe language changes working the way a telephone game would, where over centuries, the easier processibility and learnability of monosyllabic words with long vowels influenced that more and more monosyllabic words got long vowels.

This gradual language change can be seen by the fact that our grandparents, ourselves, and our children speak slightly differently.

Matzinger said: “One can imagine language change like a telephone game. One generation of speakers speaks a particular language variety. The children of this generation perceive, process and acquire frequent patterns from their parents’ generation more easily than less frequent ones and therefore use those patterns even more frequently.

“This second generation of speakers then transmits a slightly changed language to their own children. In our study, we showed that the general capacity of our brain to preferentially perceive and learn frequent patterns is an important factor that influences how languages change.”

Overall, they noted that this process of language learning and changing, and speech pattern adaptation, happens over many generations and over centuries – to a point where language can change so much that past varieties are hard to understand for people today.