Dr Charlotte Lennox from the University of Manchester reports on the main findings of her research and argues that children in custodial settings were an invisible group during the COVID-19 pandemic, in this second of a two-part series

Children in custodial settings have much higher rates of mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders than children in the general population. (1)

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) repeatedly expressed concerns about the safety of children in custodial settings. (2)

There is now evidence to suggest that the COVID-19 restrictions and limited social interactions had a significant impact on the general population (3) and a disproportionate impact on children’s mental health. (4)

As children in custodial settings were an already vulnerable group, there were concerns about the effect of the COVID-19 restrictions. (5)

Understanding the impact of the pandemic on children in custodial settings

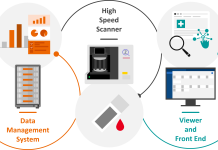

We undertook a study aimed at understanding this impact. The study consisted of three parts. We accessed all HMIP and Ofsted inspection reports for custodial settings.

We undertook an analysis to understand the policies implemented in response to COVID-19 and the impact that these policies had on children, staff and the settings.

We interviewed 41 participants, predominantly NHS staff, but we also interviewed non-NHS staff, commissioners/policy makers, professional stakeholders and children with custody experience during COVID-19.

We accessed NHS England Health and Justice Children and Young People Indicators of Performance (CYPIPs) to assess health service performance changes.

What were the impacts of COVID-19, and what was done to help?

There were direct and indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the policies implemented.

Direct impacts

Children were not considered when COVID-19 guidance was being developed for custodial settings. There was no consistency of approach across the three site types [Secure Children’s Homes (SCH), Secure Training Centres (STC) and Young Offender Institutions (YOI)], and no one government department had oversight.

This resulted in most sites adopting, to differing degrees, the COVID-19 guidelines for the adult prison estate.

However, this meant that children were locked in their rooms, in the worst cases, for 23.5 hours a day for weeks at a time. Generally, the smaller SCHs could offer more time out of their room, but this was not the case during lockdowns, on admission, or when children needed to self-isolate, they did this time on their own and locked in their rooms.

This isolation resulted in a deterioration of children’s mental health. The NHS England CYPIP data revealed an increase in referrals once restrictions were lifted compared to pre-COVID-19 rates.

‘Bubbles’ were one of the main ways sites managed children.

Initially, these were successful as the smaller groups were easier for staff to manage behaviour; keep good communication; and helped develop staff and child relationships.

However, over time these bubbles led to rising tensions and inter-bubble conflict. These issues were more apparent in the larger sites than within the SCHs.

Data from our interviews showed that the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination programme and conflicting messaging and behaviours from residential staff around vaccine take-up appeared to have an impact on childhood vaccinations more generally, with an increase in refusals for all vaccinations.

Indirect impacts

COVID-19 and policies implemented to minimise transmission affected staffing levels.

Low staffing levels impacted many aspects of life, including how the children’s behaviour was managed and their ability to access facilities, services and professionals, ultimately resulting in further restrictions and isolation.

Staffing issues were more acute in the larger sites.

Before COVID-19, NHS England commissioned the Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS) to improve children’s care quality. It aimed to do this through culture change, promoting trauma-informed, formulation-driven, whole-systems approach.

Sites were at varying stages of implementation in March 2020 (6). Our data showed that while the number of children with a formulation had increased during COVID-19, efforts to deliver the Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS) were being restricted by staffing issues within the custodial settings.

Future infection/emergency/ pandemic planning

There is a need for consistent infection control policies that are suitable for children in all custodial settings. In the future, if isolation periods are needed, this should be for the shortest amount of time, the needs of the child should be paramount, and there should be effective senior leadership in monitoring isolation.

There is a need to support settings to encourage childhood vaccination uptake, given the increase in refusals.

Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic

The use of bubbles over time within the larger sites has been problematic. While the direction of travel is for smaller Secure Schools (7), our study highlights some important considerations, particularly around group dynamics. There is also a need to address staffing issues across the sector.

Areas of practice to be refreshed

The introduction of the Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS) is likely to deliver improvements in children’s care. However, it requires sustained buy-in from all sectors, we would urge a drive to refresh uptake by the custodial settings.

References

- Beaudry, G., et al., (2021) An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis: Mental Disorders Among Adolescents in Juvenile Detention and Correctional Facilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry; 60(1):46-60.

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons (2018) Annual Report 2017-18

- Serafini G, et al., (2020) The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 22;113(8):531-7.

- Orben A, et al., (2020) The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 4(8):634-640.

- Howard League for Penal Reform (2020), Children in Prison during the Covid-19 pandemic. London: Howard League for Penal Reform.

- Anna Freud Centre (2022) Independent evaluation of the Framework for Integrated Care (SECURE STAIRS)

- Ministry of Justice (2022) Press release Construction begins at revolutionary first secure school

Note: This project is not supported by HM Prison & Probation Service or Youth Custody Services.

This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (NIHR202660). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International.