Land management is how Indigenous people have maintained a biodiverse world for generations, but now, does intervention from too many sources threaten to harm the ecosystem?

The ecosystem must function for the Earth to be able to survive climate change. The system in which we live is essential for human health and natural health – the two of which often collide, as we see now during a pandemic that particularly harms populations with bad air quality.

New ways to harm the ecosystem

Expectedly, human activity is linked to a loss of biodiversity across the world. The EU recently published a report finding that all the countries of Europe would miss their biodiversity targets for 2020, with ongoing damage to forests and animal species from sprawling human activity. They found that appropriate environment policy exists but implementation is a different story.

Land-use intensity is the increase of land productivity, due to human intervention. Though this sounds good – more work, more fruit – in reality, this leads to a problematic dependence on that human intervention. An international team of 32 scientists across 22 institutions set out to map the intricacies of how to harm the ecosystem via bad land management. They were led by Dr Maria Felipe-Lucia at UFZ, iDiv and Professor Eric Allan at the University of Bern.

What is a human-dependent landscape? And is it a good thing?

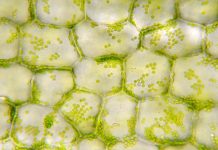

In healthy ecosystems, more species usually means higher levels of ecosystem services for people and therefore better human wellbeing. The new analyses can help to detect the loss of correlations between biodiversity and ecosystem services, which could be taken as an early warning signal of ecosystem change.

Alan commented: “Intensification tends to homogenize biodiversity-functioning-service relationships and lead to a less integrated system with fewer positive relations between services.”

“Diverse low intensity systems can provide different sets of services and a varied landscape could therefore be the key to solve conflicting land uses and provide a wider range of services while preserving biodiversity.”

“We also identified the level of management intensity that disrupts the normal functioning of the landscape, that is, when the ecosystem becomes more dependent on human inputs (such as fertilizer) for its functioning,” said Felipe-Lucia.

The researchers investigated how these interactions vary with land-use intensity. They analysed data from 300 German grasslands and forests, all different in land-use intensity, and borrowed approaches from network analysis to characterise the overall relationships between biodiversity, ecosystem functions and services.

The study demonstrates that low intensity farming and forestry can provide material benefits (fodder, timber), while preserving biodiversity. In contrast, high intensity practices increase material benefits but reduce biodiversity and the benefits people derive from it.

The small business metaphor

“With increasing land-use intensity we are losing specialized relationships,” Felipe-Lucia concludes. “This is comparable to shopping either in a low-quality mega-store or in a specialized boutique.”

Similar to specialised boutiques, where it is necessary to visit many different of them to get the best items, low land-use intensity grasslands and forests are specialised in a particular set of biodiversity, functions and associated services. High land-use intensity landscapes are comparable to mega-stores where all kinds of goods can be found at one place, but of lower quality.

Alan further commented:

“As in any city, it is ok to have a couple of mega-stores, but we cannot neglect the smaller high-quality boutiques either. In our landscapes, we need to maintain pockets of low land-use intensity to provide these specialized gifts.”