Overconfidence bolsters anti-scientific views as the further an individual strays from science, the stronger their opinions become

Education has long been considered key to enlightening the public and encouraging them to seek out science over propaganda.

Historically, the scientific community has relied upon this to increase engagement with scientific consensus. However, research from Portland State University may explain why this approach has seen only mixed results.

“Human opposition to scientific consensus is an extremely important topic. For many years, smart people thought that the way to bring people more in line with scientific consensus was to teach them the knowledge they lacked. Unfortunately, educational interventions haven’t worked very well,” comments Nick Light, a PSU assistant professor of marketing.

Light’s research titled “Knowledge overconfidence is associated with anti-consensus views on controversial scientific issues,” was published recently in Science Advances.

‘If people think they know a lot, they have minimal motivation to learn more’

“Our research suggests that there may be a problem of overconfidence getting in the way of learning, because if people think they know a lot, they have minimal motivation to learn more.

“People with more extreme anti-scientific attitudes might first need to learn about their relative ignorance on the issues before being taught specifics of established scientific knowledge,” explains Light.

Analysing anti-consensus views on 8 divisive topics

The paper examined attitudes about the following eight issues with scientific consensus on which anti-consensus views persist:

- Climate change

- Nuclear power

- Genetically modified foods

- The big bang

- Evolution

- Vaccination

- Homeopathic medicine

- COVID-19

Generally speaking, as people’s attitudes on an issue get further from scientific consensus, their assessments of their own knowledge of that issue increases, but their actual knowledge decreases, argues Light.

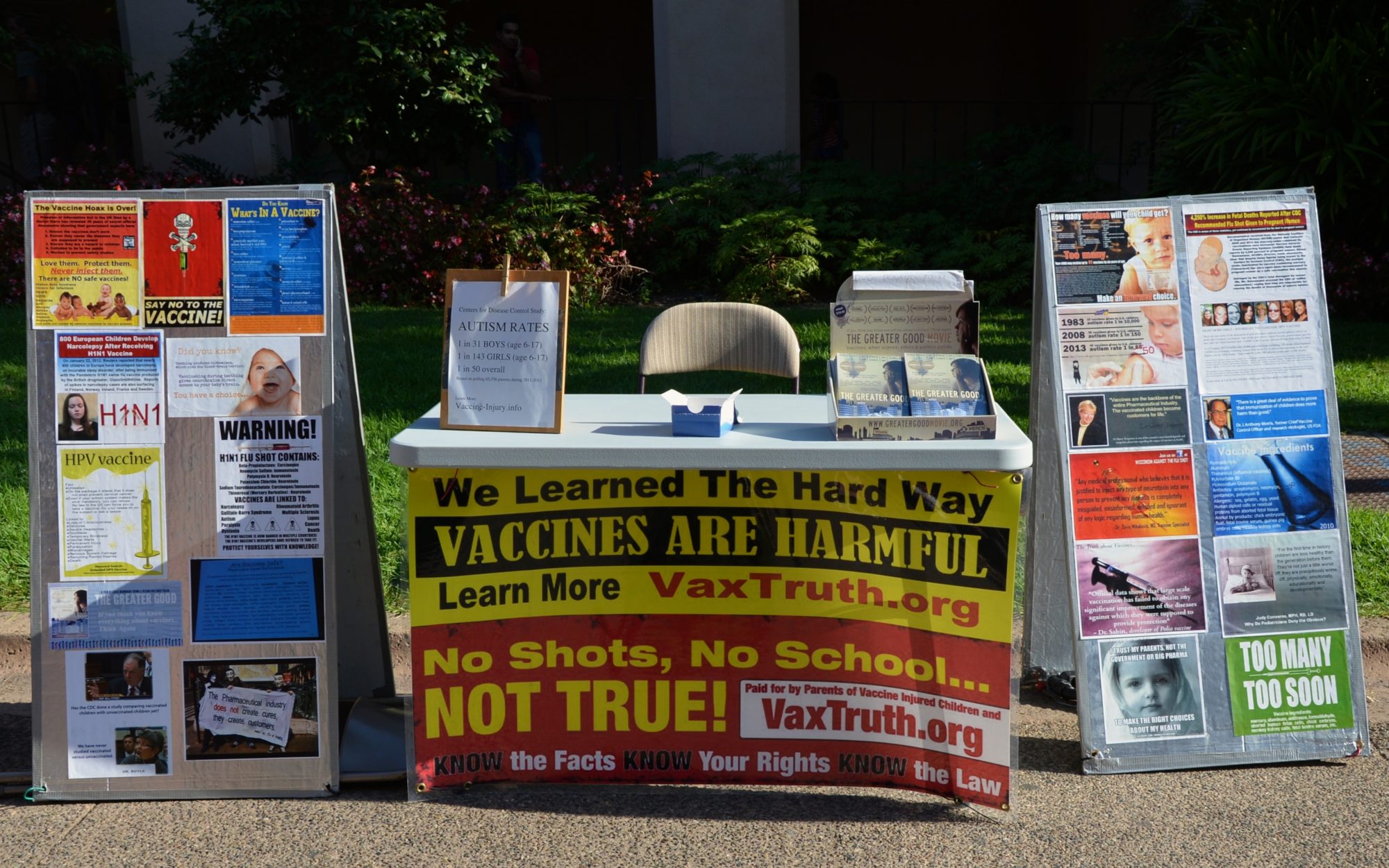

Anti-vaxxers display classic signs of overconfidence

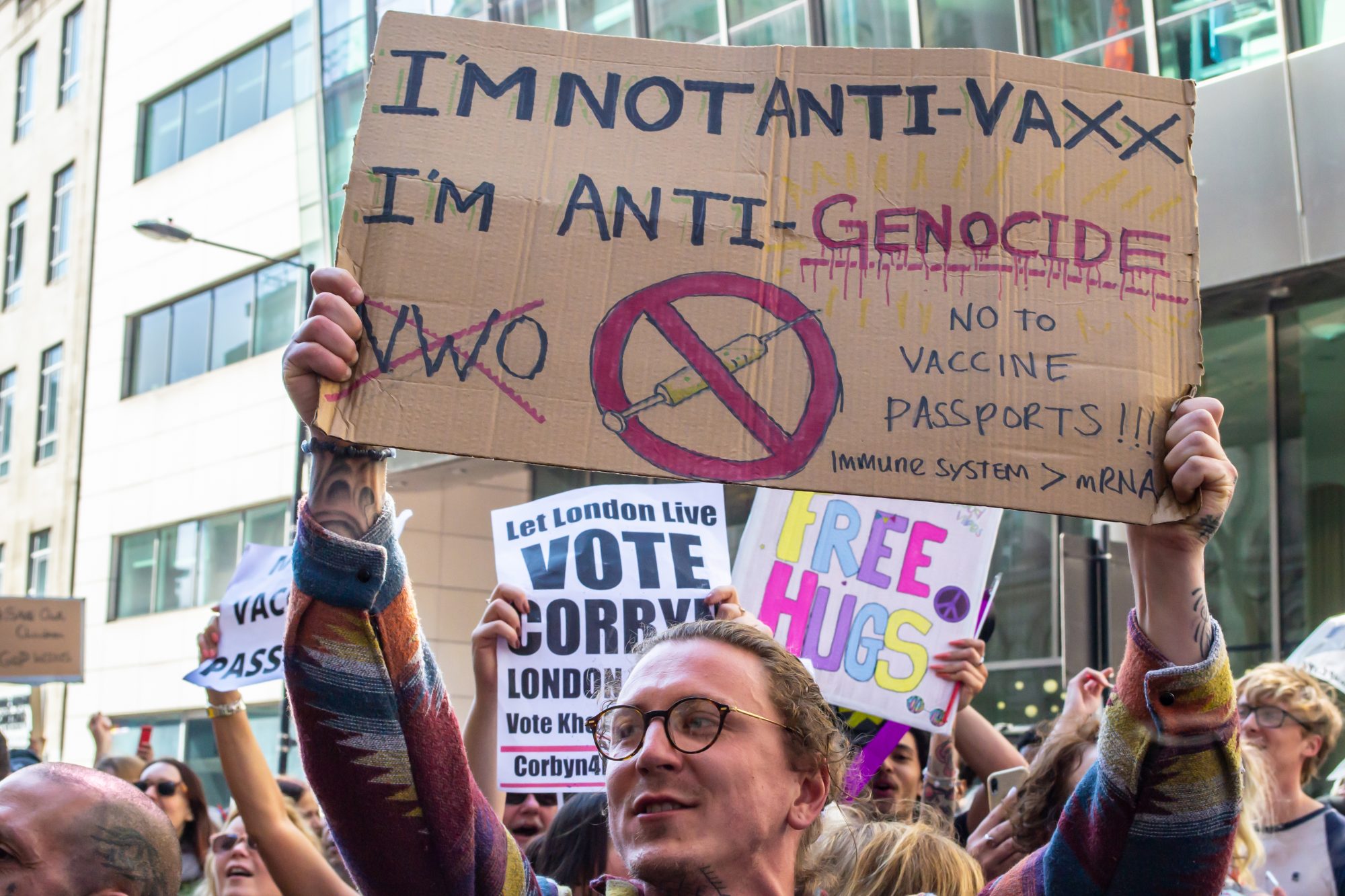

A perfect example of this is COVID-19 vaccines. An individual who strays from the science around COVID-19 vaccines is likely to foster more extreme views as they believe that they know more about it when factually their knowledge is likely to be lower.

“Essentially, the people who are most extreme in their opposition to the consensus are the most overconfident in their knowledge

“Our findings suggest that this pattern is fairly general. However, we did not find them for climate change, evolution, or the big bang theory” says the leader researcher.

Political and religious identities do play a role in overconfidence and anti-scientific views, explains Light. They can sometimes affect whether whether this pattern exists..

“For climate change, for example, attitudes in line with science tend to be held by liberals, whereas for an issue like genetically modified foods, liberals and conservatives tend to be fairly split in their support or opposition.

“It could be that when we know our in-groups feel strongly about an issue, we don’t think much about our knowledge of the issue” notes Light.

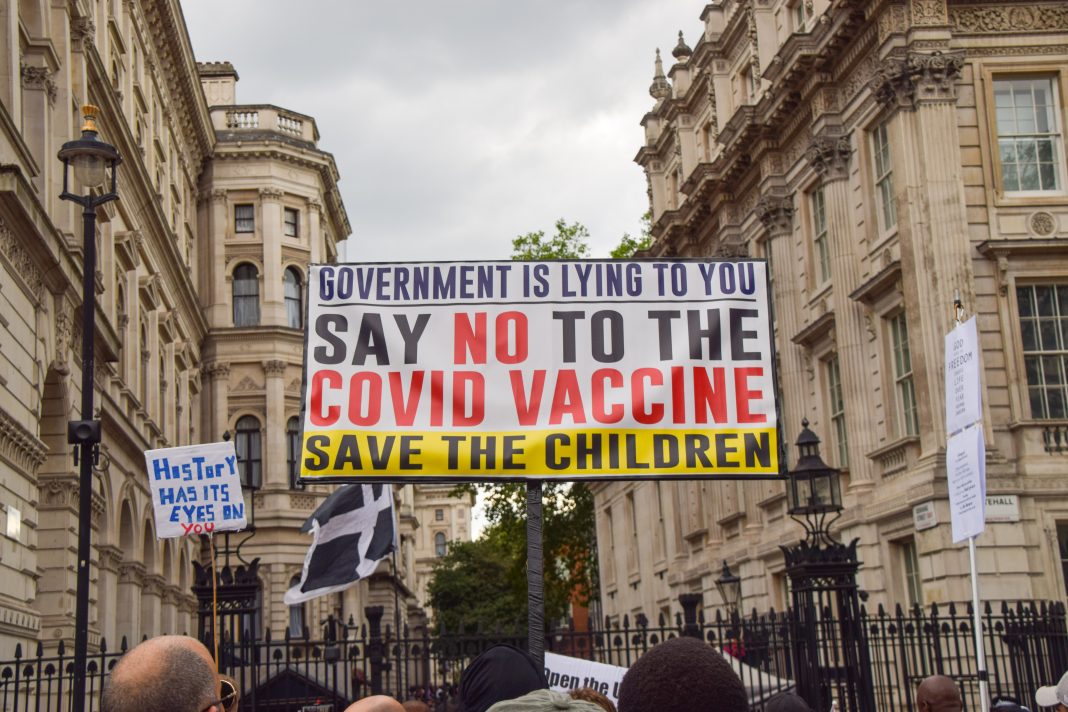

Consequences of anti-consensus views

Anti-consensus or anti-scientific views, as a result of overconfidence, have widespread consequences. Overconfident individuals who fuel anti-science propaganda can lead to property destruction, malnutrition, financial hardship and death.

It is vital that we use educational interventions to shift these views. First, overconfident individuals must get an accurate picture of their own knowledge of an issue’s complexities.

The challenge then becomes finding appropriate ways to convince anti-consensus individuals that they probably aren’t as knowledgeable as they think they are

“The challenge then becomes finding appropriate ways to convince anti-consensus individuals that they probably aren’t as knowledgeable as they think they are,” Light said.

Light and his co-authors suggests shifting focus from individual knowledge to the influence of experts.

Social norms can massively influence even the most overconfident people, despite their personal views. They provide the example of mask-wearing in Japan. The majority of people in Japan wore masks not to mitigate personal risk, but to conform to a societal norm.

“People tend to do what they think their community expects them to do. While blindly following the consensus isn’t generally recommended, if anti-consensus attitudes create dangerous situations for the community, it is incumbent on society to try to change minds in favour of the scientific consensus,” Light concludes.

It says it all, you are absolutely right.