Dr Sue Carter, Director, Emerita of The Kinsey Institute, argues that emotionally powerful social behaviours are built upon primal functions in her fascinating discussion on peptide pathways to human evolution

Human evolution and unique features of the human brain can be traced to archaic chemical processes that began to appear over 600 million years ago. Amino-acid based molecules known as peptides, capable of reducing dehydration, allowed animals to move from aquatic environments to dry land. Particularly relevant to the evolution of modern mammals are two small peptides, oxytocin and vasopressin. Of these, vasopressin is more ancient. Oxytocin appeared much more recently and is central to the traits that define modern mammals.

Both oxytocin and vasopressin tune the central nervous system, setting the neurobiological stage for adaptive patterns of physiology and behaviour. Vasopressin is associated with anxiety and defensive behaviours increases blood pressure and allows mobilisation in the face of danger. Oxytocin permits mammals to overcome the fear of others and use social relationships and cognition to cope with challenges and trauma.

These biochemical building blocks and their receptors are foundations for mammalian sexuality, birth, lactation and the capacity to adapt in an ever-changing environment. The same molecules that protect our bodies and allow reproduction, also facilitate our capacity to form social bonds and defend ourselves and those for whom we care.

Chemistry and bonding

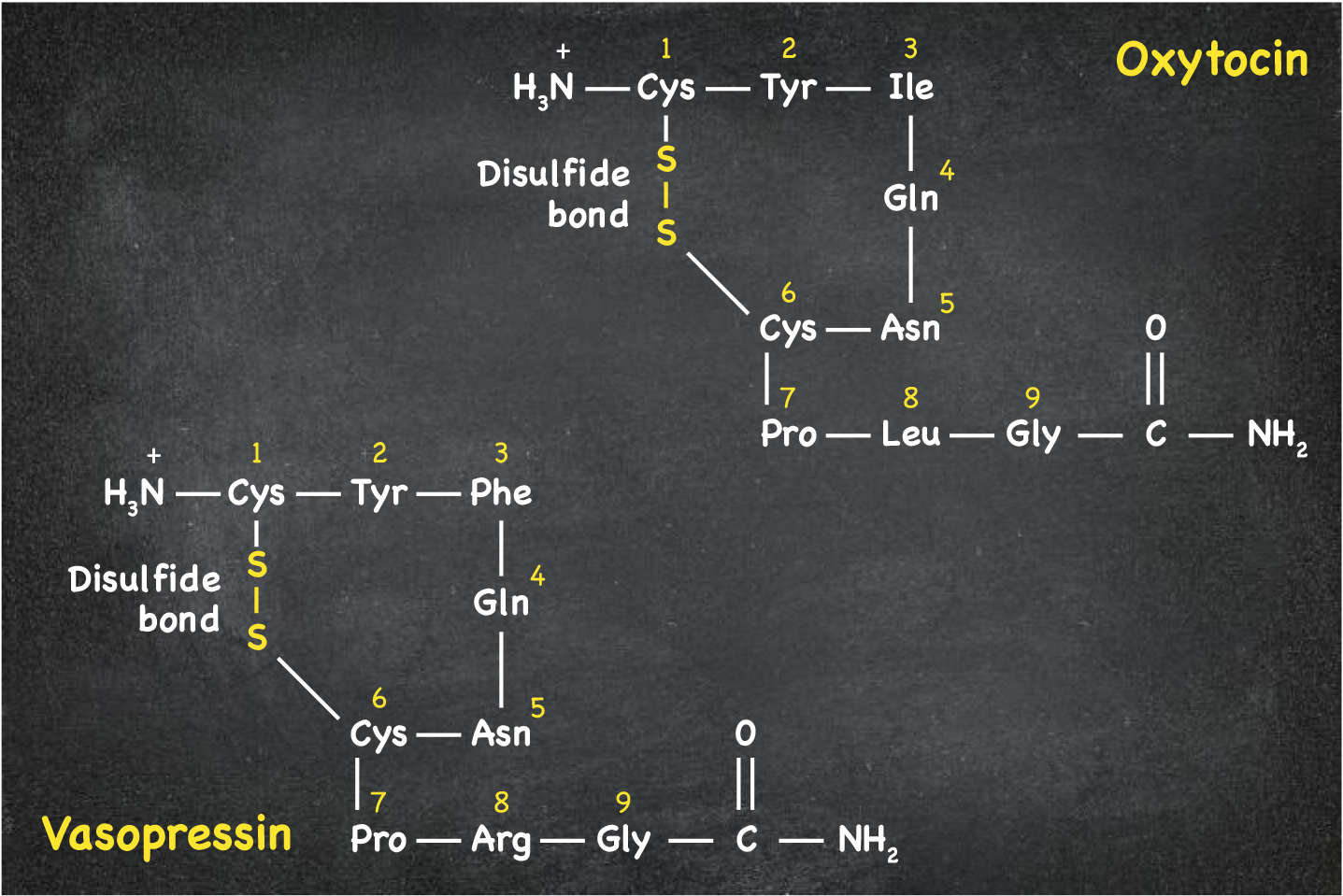

Oxytocin and vasopressin are partners in a dynamic biochemical dance. Both consist of nine amino acids with 6 amino acid rings that are held together by disulfide bonds (Figure 1). Oxytocin influences the functions of vasopressin and vice versa, in part because these peptides are capable of binding to each other’s receptors. Most of the oxytocin and vasopressin in the body is synthesised in the brain. However, receptors sensitive to these peptides are found throughout the body giving these molecules a central role in coordinating many physiological functions.

Other hormones including gonadal and adrenal steroids also regulate both peptides and their receptors. When better understood, the interactions among these will likely help explain much of their biological versatility, ranging from the bonds formed between molecules to the selective relationships found in society.

Do oxytocin and vasopressin help to explain human nature?

Oxytocin played a central role in the evolution of the mammalian nervous system and may lie beneath the surface of several mysteries associated with human existence. Both the birth of a baby and releasing milk are facilitated by oxytocin’s effects on muscles. In the postnatal period mothers (or comparable caretakers) provides milk and nurture to the dependent newborn.

Falling in love with a baby also appears to be facilitated by oxytocin in both males and females. Bonding to an infant can occur in the absence of birth or lactation, providing several layers of physical and emotional support for the newborn. The human experiences of orgasm and, in males, ejaculation also are facilitated by oxytocin, possibly reinforcing adult social bonds.

Unique human traits including complex social cognition and language rely on the functions of the human cortex. The cortex requires a sophisticated autonomic nervous system and high levels of oxygen. The autonomic nervous system is dynamically regulated by both oxytocin and vasopressin, with abundant peptide receptors in the brainstem.

Vasopressin is a stress hormone, while oxytocin is of particular importance in “stress-coping,” encouraging a sense of safety that allows positive social interactions even during periods of adversity and trauma. Across the lifespan, oxytocin may modulate emotional reactivity and increase social sensitivity.

During mammalian development, variations on these same molecules help physically sculpt the brain, heart and other tissues. Oxytocin can heal wounds and has therapeutic consequences throughout the body. For example, oxytocin appears to be a protective factor against cardiovascular disease, possibly by reducing inflammation and blood pressure, while vasopressin generally has opposite effects.

A mother’s body is physically remodelled in part by oxytocin, eventually allowing birth. Oxytocin stimulates smooth muscles, such as those in the uterus, creating rhythmic contractions that are associated with sex and birth. Oxytocin is of special importance to humans, in which infants have comparatively large heads and communicative faces. Oxytocin plays a major role in the innervation of the face and facilitates social communication.

Oxytocin physically and functionally shapes the neocortex, allowing a nervous system capable of language and social cognition. Oxytocin also is analgesic and protects both mother and infant from pain and the memory of pain associated with childbirth. Oxytocin functions in conjunction with other molecules, including dopamine and opioids, to transform experiences from pain to pleasure and to reduce the consequences of traumatic stress.

Although characterised initially as a “female reproductive hormone,” it is now clear that oxytocin acts in both sexes. In contrast, vasopressin, especially in brain regions associated with defence, is regulated by androgens and of particular importance in males. Both sexes use changes in the vasopressin system to adapt to threatening experiences, but there is increasing evidence that males are more sensitive to vasopressin than females. Males may show a more mobilised response to danger, while females tend to respond to apparently similar stressors with immobilisation or anxiety.

Depression and a tendency to emotionally shutting-down after a traumatic experience are two to four times more likely in females than males. Vasopressin can support active defensive behaviours and lowers thresholds to aggression. It is also possible that sex differences in aggression and reactions to infants are at least partially due to sex differences in sensitivity to vasopressin and oxytocin.

Pathways to peace

In a world torn by fear and violence, it is easy to forget that humans are the primates that rely most strongly for their survival on social relationships. Knowledge of the roots of both peace and war are critical to our future as a species. The deeply-buried secrets at the core of human evolution are only now being uncovered, via peptide pathways.

Understanding the actions of peptides and especially oxytocin is offering new perspectives into the physiological and evolutionary origins of what it means to be human. This knowledge also suggests pathways through which we may optimise human health and wellbeing.

Suggested reading

Carter, C. S. 2014. Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology 65:17-39.

MacLean, E.L, Wilson, S.R., Martin, W.L., Davis, J.M., Nazarloo, H.P., Carter, C.S. 2019. Challenges for measuring oxytocin: The blind men and the elephant? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 107:225-231.

Hrdy, S. B. 2011. Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Harvard University Press.

*Please note: This is a commercial profile