Professor Malcolm Mason, Cancer Research UK’s Prostate Cancer Expert reveals why prostate cancer is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma

Every year around 13,000 men in the UK die of prostate cancer. So it seems obvious that prevention and early detection ought to be the cornerstone of our strategy alongside new and better treatments for men who have this life-threatening disease. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Prostate cancer – unlike other cancers – is a disease most men (especially those over 60) have, but it’s usually an indolent condition that isn’t life threatening.

There is huge public interest in PSA (a protein produced by cells of the prostate gland) as a ‘simple blood test’ for the early detection of prostate cancer. This has been fuelled by celebrities who have either been diagnosed and treated successfully following a PSA test, or who were found to have incurable and advanced prostate cancer having never had a PSA test. There is far less public interest in the hard evidence.

PSA undoubtedly detects more prostate cancer than we would otherwise diagnose. A recent study found that for men who have been diagnosed this way, the risk of dying from the disease over a 10-year period was only around 1%, even if they had no treatment and were put onto a surveillance programme.

What does this mean? PSA appears to be particularly good at finding men who have the usual, slow growing, non-life-threatening form of prostate cancer but is less good at finding men who have aggressive prostate cancer. Bluntly, most men, whose cancer is diagnosed after a PSA test, do not need treatment, although many of them may end up having it. Further proof of this comes from a study which showed that offering otherwise healthy men a single PSA test as a way to ‘screen’ for prostate cancer makes absolutely no difference to their chances of dying from the disease after a 10-year period.

Some advocate a more intensive use of PSA, rather than using a ‘one-off’ reading, but this is controversial as many men will still receive unnecessary treatment in the ‘first sweep’ of PSA testing. More promising avenues of research are other tests to complement PSA. Clinical trials have indicated that an MRI scan is a good way of picking out men whose PSA level is elevated, but who do not need a biopsy.

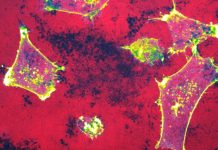

In the future, modern techniques in molecular genetics and molecular biochemistry may be able to identify men at higher risk of developing life-threatening prostate cancer. It will be some years before we know whether combining these molecular tests with an MRI plus PSA can provide an answer, but it is an exciting prospect.

Another vital aspect we need to improve is identifying men at high risk of developing prostate cancer.

We know that Afro-Caribbean men, men with an extremely strong family history of the disease (especially families with multiple close relatives diagnosed at a very early age), and men who carry a mutation in the breast cancer gene BRCA-2, are at increased risk. But there are other men at high risk in the population, and to date we don’t know who they are. We must research ways to find them.

At the other end of the spectrum are men with disease that we know to be aggressive. Clinical trials have shown that for many of these men, local treatment with radiotherapy (and presumably surgery) prevents death from prostate cancer.

For men with advanced disease, Cancer Research UK’s STAMPEDE trial showed that early use of chemotherapy, or one of the newer anti-hormonal agents, plus standard therapy, prolongs survival even if it doesn’t cure the disease. These are now the gold standards of care.

But waiting in the wings are generations of newer treatments which target specific molecular defects in prostate cancer cells.

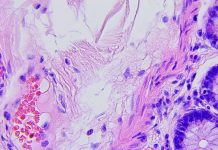

We now know that what we call ‘prostate cancer’ is a spectrum of diseases which vary immensely in what goes wrong at the genetic or molecular level. Some of these new biological treatments target subpopulations of men whose cancer has a specific defect. For example, the drugs known as PARP inhibitors might target cancers which have a defect in their ability to repair DNA. Our understanding of these new concepts is in its infancy. Ongoing research will expand our knowledge and maybe even lead to new treatments that we can’t yet imagine.

Our hope is that through these two strands of research – pin pointing and diagnosing men at risk of aggressive cancer and developing new treatments for men with specific molecular subtypes of advanced cancer – we can save lives. Both these strands go hand in hand and should lead us to the same group of men – those who, today, die of prostate cancer despite our best efforts.

Professor Malcolm Mason

Cancer Research UK’s Prostate Cancer Expert

Tel: +44 (0)300 123 1022