Chris Girard, Associate Professor, Florida International University, explains how rural-urban cleavages in Afghanistan are revealed by coevolving informatics

Refugee outflow surged when Taliban fighters, long entrenched in rural areas, seized Kabul in August of 2021. Afghanistan’s massive exodus—in addition to 82 million forcibly displaced people worldwide—displays rural-urban cleavages. A key dynamic creating these cleavages is revealed by digital-age coevolving informatics[1].

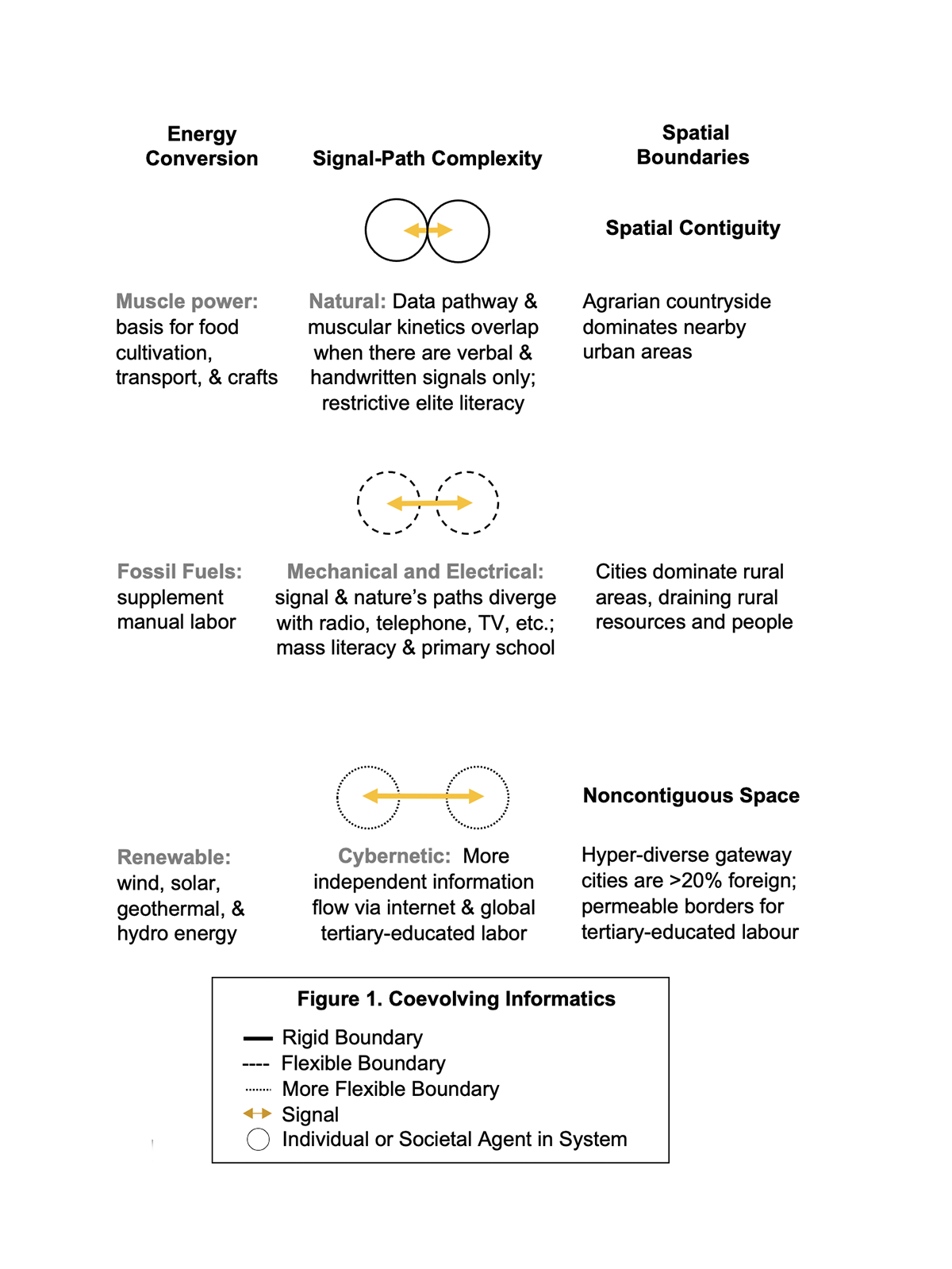

Coevolving informatics focuses on information flows concentrated in cities. Greater urban complexity enables more cultural and overall information-pathway independence from two crosscutting physical limitations: energy-conversion and distance (Fig. 1). Metropolitan culture spawns distance-bridging innovations such as more energy-efficient transportation and faster data processing. Urban jobs and freedoms draw rural migrants to cities like Kabul.

Nevertheless, urban innovations also impose nonmetropolitan physical constraints. Heartland culture and livelihoods are displaced, sometimes instigating rural insurgencies and outmigration. A key example is schooling for women and other reforms imposed on rural Afghans by Kabul’s Saur revolution. Ensuing chaos triggered Soviet military intervention from 1979 to 1989. Decades of warfare (1979-2021), often directed from foreign capitals supplying high-tech weapons, launched massive refugee outflows that continue today. Afghanistan’s urban-rural tensions reflect global energetic and cultural cleavages.

Information-driven rural-urban cleavages and migration

Historically, urban culture has been constrained by rural energetics. Early preindustrial cities – 10,000 years ago – freed as much as 5% of a society’s population from expending muscle power on foraging or farming. The city’s freed-up information pathways circulated intellectual capital, fostering the production of tools, writing, vehicles, etc. Yet the dependence of urban economies on muscle-powered rural-sector energetics puts limits on the proportion of a society’s population that can be fed and sheltered in cities. For example, before Afghanistan’s four-decades-old war, more than 90% of farmers ploughed fields with oxen. Threshing and seed broadcasting was done by hand. This put geospatial constraints on metropolitan development, as is evident from nearly 80% of Afghanistan’s population remaining rural up to the present.

In the mid-18th century, urban innovations overcame rural energy constraints. Fossil fuels powered assembly-line production. Because fossil-fuel energy supplements muscle power, manufacturing and mechanised farming could rapidly expand output to accommodate massive rural-to-urban migration. Today in Afghanistan, at least half of farmers rent tractors to prepare their fields. At the same time, Kabul’s population has expanded from under one million in the 1970s to over four million today. Yet Afghanistan’s mechanised warfare (1979-2021) has ravaged rural infrastructure and turned farmers into refugees. Much of the strategic planning (information flow) came from foreign capitals such as Moscow and Washington D.C. In sum, Afghanistan’s rural-urban cleavages were magnified by foreign metropolitan culture.

Recently, high-tech urbanism is overcoming fossil-fuel and smokestack-industry energy constraints, creating new cleavages. More than 100 cities worldwide now get at least 70% of their electricity from renewable energy. Cost-reducing innovations for this technology are advanced by the information-path independence of tertiary -educated foreigners migrating freely. Accordingly, many high-tech cities have become “hyper-diverse gateways” that comprise at least 20% foreign-born (Fig. 1).

Among foreign-born workers, those with tertiary education are four times more likely to emigrate than less-skilled workers. Conversely, manual workers—relying on muscle power—are more likely to be blocked from legal entry or citizenship in rich destination countries. Moreover, high-tech information-path independence has created rustbelt shock. In areas relying mostly on smokestack industries, outmigration occurs because of job loss, declining amenities, and abandoned mills and mines. In Afghanistan, the economy increasingly demands independent (nondomestic) expertise, such as the World Bank experience of former president Ashraf Ghani. In sum, global metropolitan information flows are becoming increasingly detached from manual labour and from rustbelt and rural culture.

Gender, refugees, and national identity

Urban-rural cleavages deepen when non-traditional norms, such as gender equality, diffuse among global cities. Disseminating this metropolitan culture, colleges now enrol more women than men in 96 out of 137 countries. Afghanistan’s biggest city is not insulated from these global influences. For example, an organiser of Kabul’s revolutionary coup in 1978, Hafizullah Amin, purportedly became radicalised while studying in the U.S. (Columbia University and University of Wisconsin).

Prior to Amin’s assassination in 1979 as Afghanistan’s president, the revolutionary regime introduced mandatory schooling for women and other reforms. These reforms undermined rural customs. Educating women was seen as dishonourable by Pashtun farmers, who initiated an insurgency and started fleeing to Pakistan. The insurgency triggered Soviet military intervention (1979-1989) that thrust close to six million additional refugees into Pakistan and Iran. A subsequent U.S.-led intervention (2001-2021) also triggered a massive refugee outflow. At a cost, both the Soviets and the U.S. promoted a metropolitan agenda including women’s education and women’s rights.

Urban-rural cleavages transcend Afghanistan. When sidelining heartland dislocations, innovations in globally linked cities create a domestic backlash. For less globally connected non-professional and rural constituencies, their national identities draw on homeland institutions and narratives that may intersect with religious tradition. On this foundation, Afghanistan’s madrasa-educated Taliban was able to build a national religious (Islamic) identity that spurns foreign domination or influence.

Taliban ideology rejects big-city innovations that undercut Afghanistan’s traditions. Coevolving informatics places this conservative ideology in the context of global urban-rural cleavages. Notably, nationalism-infused opposition to globalist big-city culture is also present in the U.S. and Europe (e.g., Brexit). This partly results from declining rustbelt and rural energetics. Ultimately, big-city information flows produce unsustainable chaos when urban elites disregard nonmetropolitan dislocations.

[1] Girard, C. Globalization and the erosion of geo-ethnic checkpoints: Evolving signal-boundary systems at the edge of chaos. Evolutionary & Institutional Economics Review 2020, 17, 93-109.

Please note: This is a commercial profile