Tomaso Aste and Geoff Goodell from University College London’s Centre for Blockchain Technologies share their views on why blockchain technology is for the public good and about the fundamental design constraints and digital identity protocols in a human rights context

Digital technologies offer great potential for the marginalised populations of the world in many dimensions of their lives, including communication, commerce, financial inclusion, disaster recovery and the delivery of aid. However, digital technologies can also play a divisive role. By enabling the powerful who can access key information and who have the capability to develop infrastructure, it often penalises those who cannot, especially the most disadvantaged. This is consequently increasing inequality and marginalisation. In this respect, technology is not neutral, and its design can strongly influence and shape our future society.

We argue that distributed ledger technologies present an opportunity for marginalised populations, by empowering them to manage their data and business practices and achieve demarginalisation by involving the community in a decentralised manner. Distributed ledger technologies allow cooperative actions for marginalised populations to refocus away from the most powerful gatekeepers and ease the conflicting interests between governments, non-government organisations and entrepreneurs. Here we present fundamental design constraints for digital technology services in a human rights context. We also discuss an approach for decentralised digital identity that complies with these fundamental design constraints.

Centralised infrastructure is economically efficient and may create value, both financial and political, for those groups who authorise, build, operate and oversee the systems that use it. Often, the interests of such groups are not aligned with the populations they serve. Some service providers are drawn by the promise of operating a central hub that everyone must use, thus allowing them to collect economic rents on an indefinite basis. Other businesses are drawn by the promise of collecting, aggregating, analysing, or selling data about individuals for profit. State actors are drawn by the opportunity of controlling the behaviour of their constituent populations through surveillance.

Infrastructure with decentralised governance, by contrast, affords no such incentives for its development and relies on local actors to see the benefit of its value. Deploying infrastructure with decentralised governance is a particularly challenging task because it impacts existing business models based on asymmetry of information and disrupts local incumbents that may already benefit unfairly from existing centralised control points. To create decentralised infrastructure, we must activate a multi-stakeholder process aiming at an agreement on standards and the mechanisms by which different participants can interact. A bottom-up process for deployment of infrastructure achieves legitimacy by rightfully involving the populations that it serves, each acting in their own self-interest.

Design constraints for digital technology services

Let us first identify eight key constraints that can serve to guide our thinking about information services in a human rights context. These foundational constraints set a base for the design of ethical digital technologies that respect fundamental human rights and promote social virtue:

- Minimise control points that can be used to co-opt the system. A single point of trust is a single point of failure and both state actors and technology firms have historically been proven to sometimes abuse such trust.

- Mitigate architectural characteristics that lead to surveillance. Surveillance is about control, as much as it is about discovery: people behave differently when they believe that their activities are being monitored or evaluated. Incentives defined by powerful actors do not always serve the public interest and the opportunity to discover misbehaviour often does not justify such mechanisms of control.

- Do not impose non-consensual trust relationships on beneficiaries. If a direct trust relationship with a third-party platform provider or certification authority is required, then that counterparty is facilitating coercion. Such coercion should be recognised for what it is and not tolerated in the name of convenience.

- Disincentivise economic rent-seeking on the part of solution providers. These models provide the opportunity to achieve status as de-facto monopoly infrastructure, with network effects that shut out prospective competitors and allow extraction of value over the long-term. Such opportunities are fundamentally abusive to the users of the infrastructure.

- Empower local businesses and communities to establish their own trust relationships. The opportunity to establish trust relationships on their own terms is important for businesses both to compete in a free market place and to act in a manner that reflects the interests of their communities.

- Empower service providers to establish their own business practices and methods. Providers of key services must adopt practices that work within the values and context of their communities.

- Empower individual users to manage the linkages among their activities. To be truly free and autonomous, individuals must be able to manage the cross sections of their activities that are seen by various institutions, businesses and state actors.

- Resist creation of potentially abusive legal processes and practices. Infrastructure that can be used to abuse and control individual persons is problematic even if those who oversee the infrastructure are genuinely benign. Once the infrastructure is created, there is only a matter of time before it is used for the wrong purposes.

Establishing meaningful credentials for individuals and organisations is a problematic task, even in developed economies with strong rule of law. In an environment in which the incumbent actors are widely accepted as unscrupulous, this presents an even greater problem challenging the viability of services based on hierarchical trust networks, such as all-purpose identity cards. In many parts of the world, legitimate trust relationships are not hierarchical, and a top-down approach will not work.

Decentralised design for digital identity

Modern digital technology infrastructure relies heavily on services that often require their users to establish accounts and assert their identities as they make use of the services. For this reason, the collection, aggregation and analysis of personal data have become politically contentious issues, as the businesses that operate on such data often have little or no public accountability with respect to how the data is gathered and used. When marginalised communities are involved, the problem is exacerbated as weak public institutions are ill-suited to defend the interests of individuals and small businesses against the interests of those who seek control.

The current state-of-the-art in identity systems for social protection and financial inclusion impose non-consensual trust relationships on their users, including both the ultimate beneficiaries, as well as local authorities, service providers and others. Such trust relationships expose users to powerful central authorities with potentially corrupt or unscrupulous operators, poor security practices and the potential for coercion by politically or economically powerful actors. Identity systems that rely on a single technology, a single implementation, or a single set of operators have proven unreliable at best and in many cases, they represent a threat to human rights as well.

The alternative to imposing new trust relationships is to work with existing trust relationships. Distributed ledgers allow for system-level approaches that make it possible for existing businesses, community groups, cooperatives and service providers to continue to exercise self-determination, without forcibly requiring them to cooperate with central authorities (including governments, NGOs, operators and other institutions or service providers) or with specific platforms or implementations.

For users to retain control of their identities and to avoid the possibility that others might abuse their data, it must be possible to:

- Generate identifiers on hardware that users own and trust. Conversely, general-purpose authentication tokens issued externally, such as all-purpose identity cards, as well as inalienable tokens such as biometrics, can be used to track the behaviours of users against their wishes.

- Ensure that authentication infrastructure operators never learn meaningful identity information about their users. Infrastructure operators are naturally positioned to exploit the data that they carry. To minimise the potential for abuse, such operators must not receive or carry exploitable information in the first place.

- Separate operators of authentication infrastructure from service providers. Users must be able to exercise autonomy in making use of services, free of the concern that their various activities might be tracked and linked.

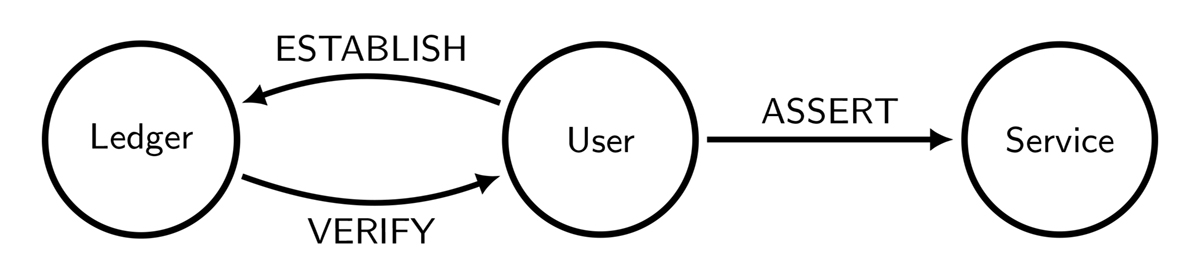

The figure above shows how such an identity system might work. An individual user can establish a credential representing an attribute or token by writing to a distributed ledger. Later, the individual can use the distributed ledger to verify the credential and assert it when requesting a service or conducting a transaction.

The best way to eliminate control points is to decentralise control. The distributed ledger would serve as a layer of indirection between the processes of establishing and asserting identity, without itself being owned or operated by any single party. As long as the community of operators of the distributed ledger remains sufficiently diverse, there would be no particular point of control to be abused without establishing many separate control relationships.

By applying cryptography and community validation to remove third-party trust from business transactions, distributed ledgers hold promise as part of the solution. By facilitating decentralised control of a transactional system, their use can mitigate the threats to human rights posed by powerful intermediaries and, their use can empower the less powerful participants, such as small businesses, local cooperatives and the individual beneficiaries themselves.

It may not be easy to convince state actors and incumbent businesses to accept the development and use of technology that disrupts current business and power models. However, with the rise of coercion and control through platform services and data aggregation, now is a fine time for those who believe in human rights to take a stand in favour of individual autonomy and dignity.

Please note: this is a commercial profile

Dr Geoff Goodell*

Professor Tomaso Aste

UCL Centre for Blockchain Technologies

Dep. Computer Science

University College London

http://blockchain.cs.ucl.ac.uk/

*also: Oxford Centre for Technology and Global Affairs