In this interview, Dr Carolyn M. Hutter, PhD, Director, Division of Genome Sciences at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) outlines the important role of research when it comes to applying genome technologies to studying disease

On 25th April 2019, National DNA Day celebrates the 66th anniversary of the discovery of DNA’s double helix and the 16th anniversary of the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP). To mark this important anniversary, we spoke to Dr Carolyn M. Hutter, PhD, Director, Division of Genome Sciences at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to learn more about their excellent work, including their role in applying genome technologies to the study of human health and disease. Genomics is a wide-ranging area and this interview covers some fascinating aspects of this, including understanding variation in the human genome and improving human health through genomics research.

By way of background, the NHGRI grew out of the international HGP project. Since the formation of NHGRI in 1997, the Institute has expanded in terms of what they do. Carolyn tells us that NHGRI is guided by a series of strategic plans, the most recent of which was published in 2011 and focuses on thinking about research from the bench to the bedside. She explains this point further, describing the ambitions of the Institute in her own words.

“We continually study everything from the structure of genomes all the way through to the application of genomics in clinical settings. At the moment, we are starting new strategic planning for our Genome 2020 vision. We kicked this off in February 2018 and are planning to have finished in October 2020 which marks the 30th anniversary of the start of the HGP.

“The Institute is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), one of the 27 Institutes and Centers within NIH, and our remit is centred around how we use genomics to understand human health. NHGRI doesn’t fund all genomics but we consider ourselves to be at the forefront of the field. We recognise that other parts of the NIH are increasingly funding genomics and we collaborate with these groups and a number of international partners.”

The Human Genome Project (HGP): From basic to clinical science

With the human genome sequence complete since April 2003, Carolyn then details the various ways in which scientists around the world have benefitted from this in the years since. This goes from basic through to clinical science in terms of how we think about things when it comes to genomics. She says that some argue that the HGP has not yet been completed because we do not yet have full sequencing for very complex areas of the genome. Carolyn then develops this thought further.

“The completion of the HGP really provided this initial backbone for that a much more specific sequencing and understanding of the structure on which of the human genome can be built on. It allows a blueprint upon which all of these other activities can happen. One of these is driving the technology and the innovation needed to sequence genomes, including the complex regions, faster, cheaper and more accurately. Those are the three things that we are always looking for in this area.

“You can also think about what it really means to understand the genome, including 3D or 4D structure of genomes. Another example is projects like The ENCODE Project: ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements, which are addressing the fact that we have not fully understood what all the genes are doing, or what all the non-coding parts of the genome doing? How do we catalogue them, start to elucidate their function, and put together pieces of that whole picture?”

Understanding variation in the human genome

Carolyn says that you can then layer on top of that additional questions, such as can we understand the variation in the genome? Or what does the variation of the genome tell us about population genetics and population structure or about the relationship between the variation in the genome and disease? She then provides more detail to us about this compelling point in her own words.

“As we start to understand the variation of the genome in relation to disease, we need to move from just saying that a part of the genome is associated with the disease to understanding the causal relationships and the mechanisms. How do we go from understanding this part of the genome is associated with the disease to translate that into ways that can benefit public health and clinical medicine?”

Improving human health through genomics research

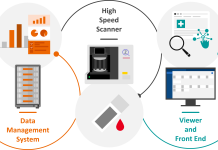

The interview then turns to look at on interesting examples of NHGRI’s work to improve the health of all humans through advances in genomics research. Carolyn stresses that their focus as an Institute is on the technologies, methods and resources to move the field of genomics forward. Although NHGRI does not have a disease focus, they do participate in exemplary disease-focused projects. As an example, they partnered with the National Cancer Institute (NCI), another branch of the NIH in the U.S., on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Carolyn noted the impact of that project on our understanding of cancer, before moving the conversation to detail more of NHGRI’s research work and the priorities for the future in this vein.

“We have a number of Genomic Medicine programmes, such as the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER) program that maps the impact of sequencing in clinical settings. Importantly, we are also building the basic understanding of the relationship between a genome and disease which is fundamentally needed to have an impact in clinical settings.

“Questions about the future priorities for genomics research and its applications to human health and disease are a key part of our Strategic Planning efforts, as mentioned above. We are really excited to have this opportunity to reach out into the community, through workshops and social media, for example, to get feedback. We have internally organised ourselves around key areas that cover basic genomics and technology, genomics of disease, genomic medicine and health, genomics and data science, and genomics in relation to education and societal issues. In all of these areas, we look forward to getting input over the next year and a half on what people see as important questions at the forefront of genomics, and to see what ideas and key areas move to the top.

“One of these key areas we have already identified is the question of how you go from variation to function to disease, and how to study this at scale in order to gain biological insight into the nature of inherited disease, insight into functional mechanisms, and ultimately to provide a rational foundation for clinical applications. We are also seeing a real need to further identify what types of genomics are ready to go into medicine and how do we effectively implement them to get there? We are also addressing how to bring together recent advances in computational biology and big data in an integrative way that allows for innovation in genomics. Important work in all of these areas is already happening, but we need to take these to the next level and draw on the exciting scientific findings that will come out of doing that type of effort well.”

Accelerating scientific and medical breakthroughs to improve human health

In closing, Carolyn shares her thoughts on how to accelerate scientific and medical breakthroughs that improve human health. She noted that as a funder, NHGRI spends a lot of time thinking about their need for a really well-balanced portfolio. As such, NHGRI needs to make sure that activity is happening at the right level in all these aforementioned areas.

“Certainly, you don’t want to go too far with investments in one specific area, because you never know where you are going to have the most important breakthroughs. This is especially true for a transdisciplinary area like genomics. In addition, we are constantly balancing the need to support fundamental resources and approaches, versus really high-risk approaches where it is less clear that they are going to pay off, but when they do a giant leap is made. Another area we consider is how best to balance large-scale collaborative research and consortia, versus investigator-initiated projects.

“It’s important that we have balance in terms of what we are funding and what we are doing in order to enable the scientific advances and breakthroughs.”

Dr Carolyn M. Hutter, PhD

Director, Division of Genome Sciences National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)

Tel: +1 (301) 480 2312