On Monday (12 July) there was a stark increase in online racial abuse against Bukayo Saka, Marcus Rashford and Jadon Sancho – with the infamously late Online Safety Bill far from becoming law, how are the Government tackling this?

When Bukayo Saka missed the final penalty for England, there were two feelings unfolding across the UK.

One feeling was loss at being so close to winning, reflecting on game strategy with an increasing sense of devastation or defiant pride, maybe both. The second feeling was a slow-burning dread, with the knowledge that game critique would become racially abusive toward the three Black athletes.

For minority ethnic football fans, the dread was as predictable as English summer rain.

On Monday, a Rashford mural in South Manchester was vandalised with racist commentary. It was commissioned in his old neighbourhood to recognise the work of the player off-pitch against child hunger. In January, Rashfords’ campaigning changed a Government contract on food parcels for children, in a moment also known as The Chartwell Scandal.

According to Twitter, over 1000 racist tweets against the athletes were removed. On Instagram, moderating AI struggled to identify monkey emojis as racist, despite being used against all three athletes.

In a 2021 report by the Runnymede Trust, they find that racial abuse online is still too difficult to stop. The report said: “Protection against racism extends to the online domain, and incitement to racial and religious hatred is illegal regardless of the medium through which it is expressed. This means that online hate speech can be prosecuted under existing hate crime legislation (mainly the Public Order Act 1986).

“However, this is inadequate to prosecute those who perpetrate hate through social media platforms, because the legislation was adopted before the mainstream use of social media.”

What is the UK Government response?

Today (14 July), when asked about the incidents of online racial abuse at PMQs, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said: “I repeat that I utterly condemn and abhor the racist outpouring we saw on Sunday night. What we’ll do, is take practical steps, to ensure that the football banning order is changed, then you won’t be going to the match.”

PM Johnson further said that he would fine all social media companies 10% of their global worth, if they appeared to cross a line.

However, in March, the Government published the Sewell Report – more commonly known as the Race Report. The report suggests that there is no “systematic racism” in the UK, explaining that any residual experiences of racism are often figments of community imagination, as opposed to real instances of discrimination. These findings are supported by the UK Government.

The Sewell Report also stated: “Often it was a perception that the wider society could not be trusted. For some groups historic experience of racism still haunts the present and there was a reluctance to acknowledge that the UK had become open and fairer.”

If the Government are biased against the existence of systematic racism, what do “practical steps” against racial abuse then look like?

PM Johnson suggested two courses of action – banning those convicted of racist hate crimes from attending football matches, and pushing forward with the Online Safety Bill.

-

The football ban plan

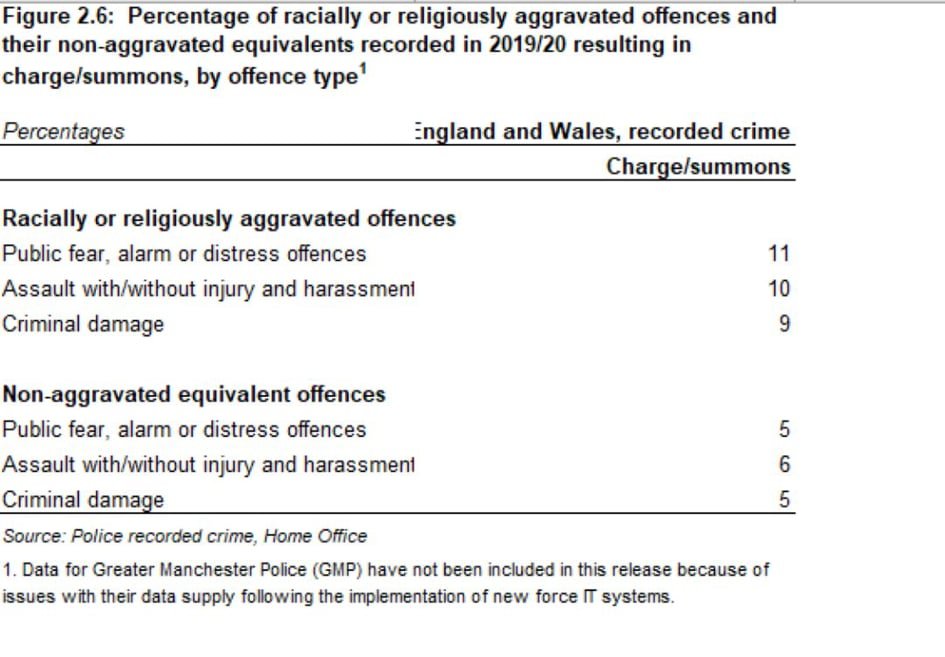

According to the latest available Home Office data from 2019-2020, there have been under 50 individuals actually charged with racially aggravated offences. This means that if the UK Government moves to stem racism by banning those charged with hate crimes, a maximum of 50 people would be missing from future stadium crowds.

Before the current moment of online racial abuse, there was debate among the Cabinet about the right of the England team to take a knee before the game. Players on both the Italian and English sides on Sunday took the knee, showing solidarity with a global anti-racist movement – which has seen athletes in the US taking a knee before their games, to remember Black lives lost to police brutality.

The UK Government, which believes there is no systematic racism, is elusive about aligning itself with anti-racist actions.

Speaking to GB News on 14 June, Home Secretary Priti Patel described the England team as performing “gesture politics”, adding: “I just don’t support people participating in that type of gesture”.

Hitting back against this statement a month later, England footballer Tyrone Mings, said:

You don’t get to stoke the fire at the beginning of the tournament by labelling our anti-racism message as ‘Gesture Politics’ & then pretend to be disgusted when the very thing we’re campaigning against, happens. https://t.co/fdTKHsxTB2

— Tyrone Mings (@OfficialTM_3) July 12, 2021

So, while the PM outlined a plan to indefinitely remove racists from football audiences, in reality the move would not stop social media abuse – just remove less than fifty people from an audience, without any deeper impact on racism.

As the Runnymede Trust said, there is currently no legislation with teeth that can address racial abuse online.

2. The Online Safety Bill

This bill, proposed in 2018, has been delayed for three years.

The Online Safety Bill was created in response to the suicide of Molly Russell. She was a 14-year-old, who made the decision to die in 2017, after participating in Instagram self-harm and suicide communities. The bill was proposed to dismantle those communities, to force tech companies to be more responsible for content and to streamline child protection legislation in the nebulous arena of the internet.

The Online Safety Bill has been waiting since then, with a series of delays, amendments and dilutions that leave it less powerful against the social media giants which are responsible for moderating content that children can see. At one point, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg even proposed plans for an Instagram that targets children under the age of 13. This was shot down by charities, but illustrated how tech giants are currently completely unchallenged by existing UK legislation.

The Online Safety Bill is also intended to regulate online racial abuse, against adults.

In May, 2021, Culture secretary Oliver Dowden announced further tweaks to the proposed legislation, suggesting it would be a “crack down on racist abuse on social media” that would “create a truly democratic digital age.”

In contrast to this change of direction, the existing draft bill does not actually discuss race or racial discrimination online. It has a sharp focus on child safety and protecting freedom of speech, while placing the regulation of racism under the vague category of “other content that is harmful to adults”.

Why the Online Safety Bill hold up?

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) fought a two year freedom of information battle to gain access to a conversation between Matt Hancock and Mark Zuckerberg. This conversation happened at a tech summit in Paris in 2018, where Zuckerberg threatened to pull funding from the “anti-tech UK government”- joking about not ‘visiting’ the UK in the same way he doesn’t visit China.

In other words, the joke suggests no further investment into the UK if tech legislation becomes more substantial.

Around the time of this meeting, Facebook employed just 2,300 staff in the UK. A few months later, Zuckerberg signed a lease on a huge King’s Cross office space – which was a significant win for the Government, in the aftermath of Brexit’s repelling effect on some international manufacturing companies.

So, will this contentious bill pass parliament?

Lord David Puttnam, Chair to the Committee on Democracy and Digital, commented: “Here’s a bill that the Government paraded as being very important but which they’ve managed to lose somehow.”

He further suggested that the proposed timeline by current Digital secretary, Caroline Dineage, would mean that the legislation would be implemented in 2023 or 2024, “seven years from conception – in the technology world that’s two lifetimes.”

![Europe’s housing crisis: A fundamental social right under pressure Run-down appartment building in southeast Europe set before a moody evening sky. High dynamic range photo. Please see my related collections... [url=search/lightbox/7431206][img]http://i161.photobucket.com/albums/t218/dave9296/Lightbox_Vetta.jpg[/img][/url]](https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/iStock-108309610-218x150.jpg)