Jason W. Loxterkamp and Pamela J. Lein from University of California, Davis, explore the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in patients with psychiatric disorders

“Timothy Leary’s dead….”

The Moody Blues, 1968

Psychedelics derived from plants have been used in religious ceremonies for centuries, and in 1938, the first synthetic psychedelic, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), was synthesised by the Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman. By 1947, LSD was marketed as a psychotherapy medication, and in 1960, Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary began popularising LSD and psilocybin, the hallucinogenic compound in “magic mushrooms”, as mind-altering therapeutics. However, by the mid-1960s, amidst growing concerns in the U.S. and Europe about the illicit production of LSD and its growing use for recreational purposes in the absence of medical supervision, the U.S. Congress passed the Drug Abuse Control Amendments, making it a misdemeanour to manufacture or sell LSD without a license. By 1970, psychedelic research was largely halted by the passage of the Controlled Substances Act of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act in the U.S. and similar legislation in Europe. Timothy Leary’s vision for psychedelics indeed seemed dead, as foretold by Ray Thomas of the Moody Blues.

However, over the past decade, a resurgence of clinical research has shifted perceptions that psychedelics are neurotoxic substances to potential therapeutics for psychiatric disorders. Globally, psychiatric disorders are a major public health problem, affecting approximately 350 million people, many of whom do not respond to conventional treatment. Recent clinical evidence suggests psychedelics can help these patients.

What are psychedelics?

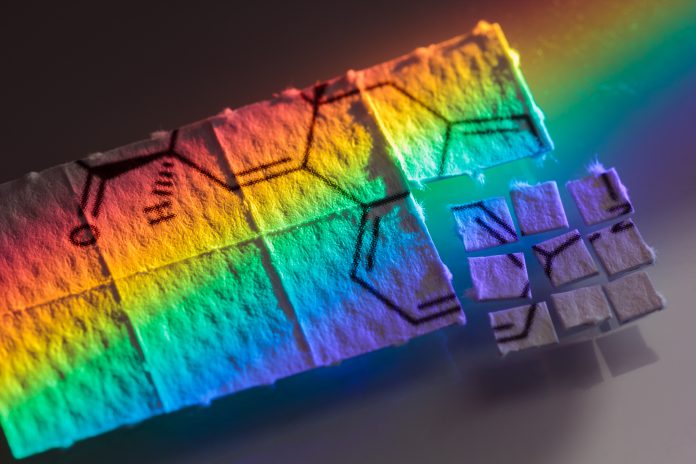

Psychedelics are chemicals that alter one’s perception of reality by modulating how nerve cells in the brain communicate with each other. In addition to LSD and psilocybin, psychedelics include ketamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known as MDMA or ecstasy, and phytocannabinoids, the psychoactive chemicals in marijuana. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) classifies these drugs according to their potential for abuse: LSD, psilocybin, MDMA, and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (∆9-THC), a psychoactive phytocannabinoid in marijuana, are classified as schedule I controlled substances with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Ketamine is classified as a schedule III controlled substance with “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence.”

These drugs can also be classified according to their psychoactive effects. LSD, psilocybin and MDMA are hallucinogens. MDMA also has stimulant properties, meaning it can elevate mood and increase alertness and energy. Simulants are often highly addictive and can cause paranoia over time. Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic, defined as distorting sensory perceptions and causing feelings of disconnection or detachment. Counterintuitively, at lower doses, ketamine can act as an “empathogen”, promoting feelings of sympathy and empathy. ∆9-THC in marijuana has hallucinogenic, stimulant and depressive actions.

Chronic use or high-dose acute exposure to psychedelics can be neurotoxic, causing addiction, paranoia, panic attacks, high blood pressure and, in severe cases, loss of consciousness and seizures. Both human and animal studies demonstrate that toxic exposures to psychdelic drugs can change the structure and function of the brain, possibly by causing excessive or overstimulation, oxidative stress or neuroinflammation. The developing brain is especially vulnerable to the neurotoxic effects of these drugs, because they can disrupt the normal pattern of connections made between brain cells during brain development. Children exposed to psychedelic drugs during pregnancy or breast-feeding have an increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders.

Therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs

Recent clinical studies suggest that psilocybin, MDMA, ketamine and phytocannabinoids can reduce depression and anxiety in patients who do not response to conventional treatment. MDMA and psilocybin have been designated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as “breakthrough therapies” for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and treatment-resistant depression, respectively. MDMA shows promise as a treatment for social anxiety in autistic adults and psilocybin, for cancer-related anxiety. A single, subanesthetic dose of ketamine in addition to psychotherapy can rapidly improve symptoms in patients with a major depressive disorder for up to 7 days. While preliminary, research supports the use of LSD in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Clinical data suggest psychedelic drugs may also be effective in treating substance abuse disorders, end-of-life psychiatric distress, and suicide ideation. Marijuana, and in particular the phytocannabinoid cannabidiol (CBD), can reduce pain and relieve anxiety. In addition CBD has been approved for treatment-resistant seizure disorders.

It is not clear yet how psychedelics work as therapeutics, but emerging data suggests these drugs protect against atrophy of neurons and promote outgrowth of neurites, the processes extended by neurons that determine how neurons connect with each other. Notably, neurites are diminished in many treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders. Psychedelic drugs are not being used as stand-alone drug treatments, but rather they are used on one or a few occasions during psychotherapy sessions to overcome obstacles to successful psychotherapy and to boost the therapeutic experience. It is theorised that the experience itself, rather than simply the pharmacological effects of the drug, leads to cure or sustained remission of severe, treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders.

Moving forward

Due in part to clinical studies documenting the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, 37 states in the U.S. have legalised the use of medical cannabis and cities in Colorado, California, and Massachusetts have decriminalised psilocybin. Oregon’s Measure 110 decriminalised the possession of small amounts of psychedelic drugs and increased access for medical uses. While the regulation and perception of psychedelics is changing, this should not be interpreted as meaning these drugs are considered safe. Indeed, the Sacramento County District Attorney’s Laboratory of Forensic Services reports cannabis and stimulants are among the most commonly reported substances of abuse in cases of driving under the influence of drugs (DUID) and drug seizures. Additional safety studies to determine the long-term effects of the therapeutic use of psychedelics are needed to support their clinical use. These limitations notwithstanding, the preliminary clinical data on the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs warrant further research, with particular focus on synthesising derivatives of these compounds that retain therapeutic effects while eliminating addictive and neurotoxic effects.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

I thought cave-paintings suggest an even longer application?