Nikolaos P. Ventikos from the School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, and Angeliki Stouraiti from the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) explore the environmental footprint of short sea shipping and how the EU can reduce emissions

The maritime transport of freights and passengers conducted along coastlines, without crossing oceans, is a commonly used definition for short sea shipping (SSS). In Europe, SSS has been the traditional mode of transport for centuries, used for moving goods and/or people from one port to another.

The early merchant vessels used for this purpose had a low cargo capacity, sailed mainly along coasts and their schedules were unstable as well as unpredictable. Coastal shipping has evolved significantly over the years whilst demand on the cargo volume increased.

Thus, larger, and more rugged vessels capable of accommodating a wide variety of cargo (i.e. liquid, bulk, containers, and passengers) are travelling on more fixed schedules within the SSS network(1). In 2020, around 60% (or almost 1.7 billion) of seaborne freights moved in Europe is classified as SSS with liquid bulk being the dominant type of cargo(2).

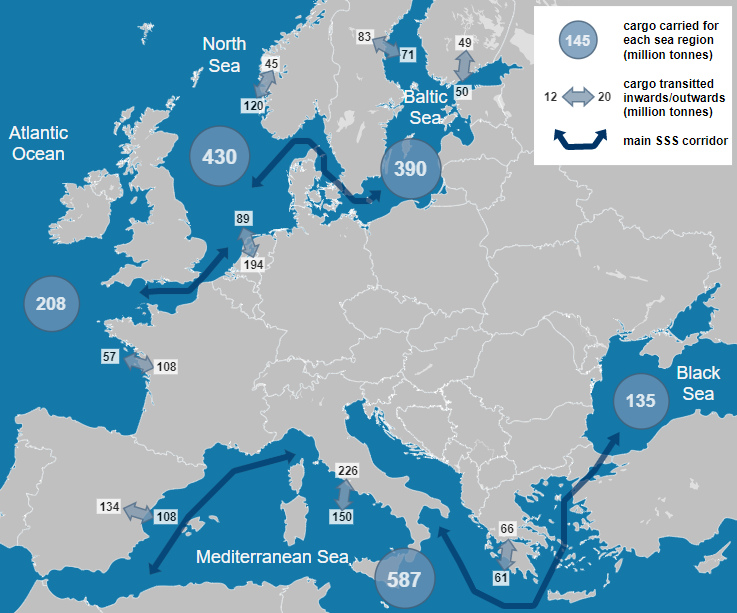

One-third of sea flows (587 million tonnes) took place in the sea region of the Mediterranean, followed by the North Sea (430 million tonnes) and the Baltic Sea (390 million tonnes) (Figure 1).

Short sea shipping will lead to lower emissions

As opposed to deep sea shipping, short sea shipping, competes with other modes of transport including road and rail. In the last years, road is the leader in transport performance representing over half of all tonne-kilometres performed in Europe, while maritime transportation is following second in modal split with a share less than a third of total transport performance(3).

Transferring cargo via roads embraces bottlenecks, with high CO2 emissions and noise pollution. SSS provides the alternative of transferring the freight around the inland, detouring major population centres. This modal shift will lead to less wear on the transport infrastructure, less congestion, fewer road accidents and lower emissions.

As a matter of fact, the last decade has been accompanied by great strides in the maritime regulatory regime regarding air pollutants by vessels’ emissions, followed by technological advancements in marine internal combustion engines. Since January 2015, vessels operating in the Baltic, the North Sea and the English Channel (i.e., SOx-Emission Control Area) are requested to consume fuel with significant limitations on the sulphur content (not exceeding 0.10%), whereas in the rest of EU waters the sulphur content is capped at 0.5% since January 2020(4).

Hence, the maritime industry focused on seeking solutions to greening the fleets. In this pathway, a lot of innovative technologies have been introduced, such as marine engines capable of consuming extremely low sulphur fuel oil, alternative fuels (e.g., LNG, methanol/ethanol, ammonia), scrubbers able to remove sulphur dioxide and ports with more environmentally conscious infrastructure (e.g., cold ironing). As a result, SSS constitutes a viable, green alternative mode of transportation.

Nowadays greenhouse gas emissions are at an all-time high with a noticeable impact on climate change. Decarbonisation is deemed imperative across all sectors. In this context, heavy-duty trucks are pushed to be electrified, with companies aiming at 50% of their sales being electric by 2030, in accordance with the Commission’s European Green Deal(5).

Research from the University of California-Berkeley pointed out the economic and environmental benefits from the decline in battery pack cost of a zero-emission truck running on electricity. Although the initial cost of an electric truck will exceed that of a conventional, the total cost of ownership per mile will end up being 50% lower, due to the reduced price of batteries, and vehicle design enhancements(6).

Another mode with electrification aspirations are railways. Rail freight transport is currently the European transport mode with the highest rate of electrification, reaching 60%(7). Even though there are no major technical hurdles in the way of electrified freight rails, the whole concept is hindered by the return of investment of low volume lines.

What is the EU doing to control shipping emissions?

The control of emissions from maritime transport is at the forefront of the EU and therefore many European programmes have addressed this issue. Indicatively, the SuperGreen project has promoted the development of green corridors and provided recommendations on sustainable freight transport.

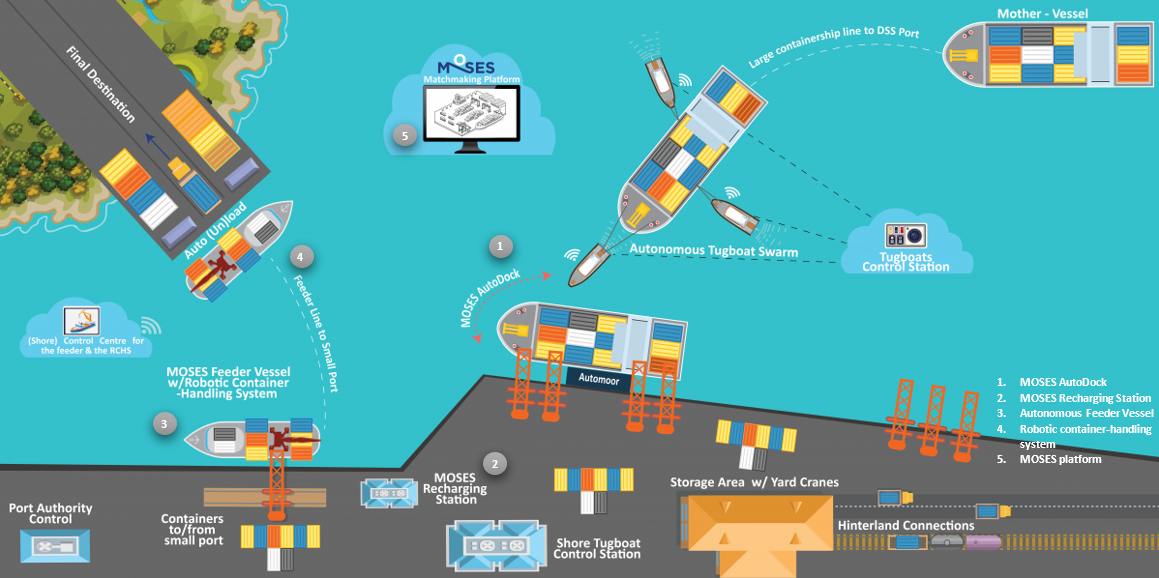

The Marco Polo project(s) has contributed to the SSS policy with the aim to eliminate traffic bottlenecks and road congestion. An objective of the ongoing project MOSES is to minimise short sea shipping emissions. The innovation of the concept relies on the introduction of a feeder vessel and autonomous tugboats with hybrid electric propulsion as well as a robotic container-handling system and automated docking system.

The assets, that are electrified, will be powered during berth by an automated shore side station, fully integrated into the port energy management system (Figure 2). The automated vessels aim to a modal shift from large container terminals to small ports in an effort to further stimulate SSS.

Transport is an integral part of the EU’s economy, capable of deeply affecting the potential for sustainable growth. To that end, it is equally as important to develop sustainable, clean modes of transportation, that can enhance the European countries’ interconnection while having minimal environmental footprint. With all the technological advancements and regulatory policies in place, SSS has the potential of incurring an emerging modal shift for a multitude of stakeholders.

With the combination of technologies that entail high levels of autonomy, the use of fuels with low or zero emissions, and a dependable yet resilient logistics chain, SSS can assume a commanding role as a green corridor in the future of a seamless infrastructure of European transportation.

References

(1) Florian Frese. What Is Short Sea Shipping? Container xChange, 2020.

(2) Eurostat. Maritime Transport Statistics – Short Sea Shipping of Goods. Eurostat, 2022.

(3) Eurostat. Freight Transport Statistics – Modal Split – Statistics Explained. Eurostat, 2021.

(4) European Commission. Air emissions from maritime transport https://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/sources/maritime.htm.

(5) European Commission. A European Green Deal; 2021.

(6) Silvio Marcacci. Cheap Batteries Could Soon Make Electric Freight Trucks 50% Cheaper To Own Than Diesel. Forbes, 2021.

(7) European Commission. Electrification of the Transport System; 2020.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.