Janeth George from SACIDS Foundation for One Health and College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, details what we need to know about enhancing the effectiveness of animal health surveillance in Africa through a systems-based integrative research approach

The importance of animal health surveillance cannot be understated. Firstly, it safeguards the health and welfare of animals. It also safeguards the safety of food to consumers of fresh or processed food of animal origin. It ensures quality assurance for trade in animals and animal products. And it safeguards human health. Animal health surveillance is part of the wider objective of One Health1 surveillance. However, it is an ever-evolving activity that needs to be backed up with scientific evidence. With increased cross-species transmission and disease impact, systems can no longer operate in isolation. Furthermore, surveillance data is the brainpower of any efficient health system. With surveillance data, we can estimate the magnitude of the problem and determine the distribution of the disease. It also helps to trace the history of the disease and monitor any changes in the pattern. Through surveillance, we can stimulate research, evaluate the control intervention and most of all, inform policy decisions.

Why integrative approaches in animal health surveillance? Experience from the research study in Tanzania

Several evaluations conducted between 2008 and 2017 on the animal health surveillance systems in Tanzania indicated the limited capacity of the national animal health surveillance system to detect and respond to disease outbreaks. The recommendations based on the evaluations were made, but there was little progress on the uptake and implementation. The persisting challenges indicate the complex interrelationships between the performance of the surveillance system and its processes, political and institutional frameworks at all levels. That triggered my curiosity to understand why there were few improvements in Tanzania’s animal health surveillance system, and what could be done to improve the situation sustainably. Therefore, the study was conducted to develop integrative solutions for improving the animal health system in Tanzania using a systems approach. The study involved a systematic review, an extensive field investigation, and systems integration. Data were collected using various techniques, including systematic review, questionnaire administration, key informant interviews, non-participant observation and stakeholders’ workshops.

Application of integrative approaches in animal health surveillance

Systems mapping

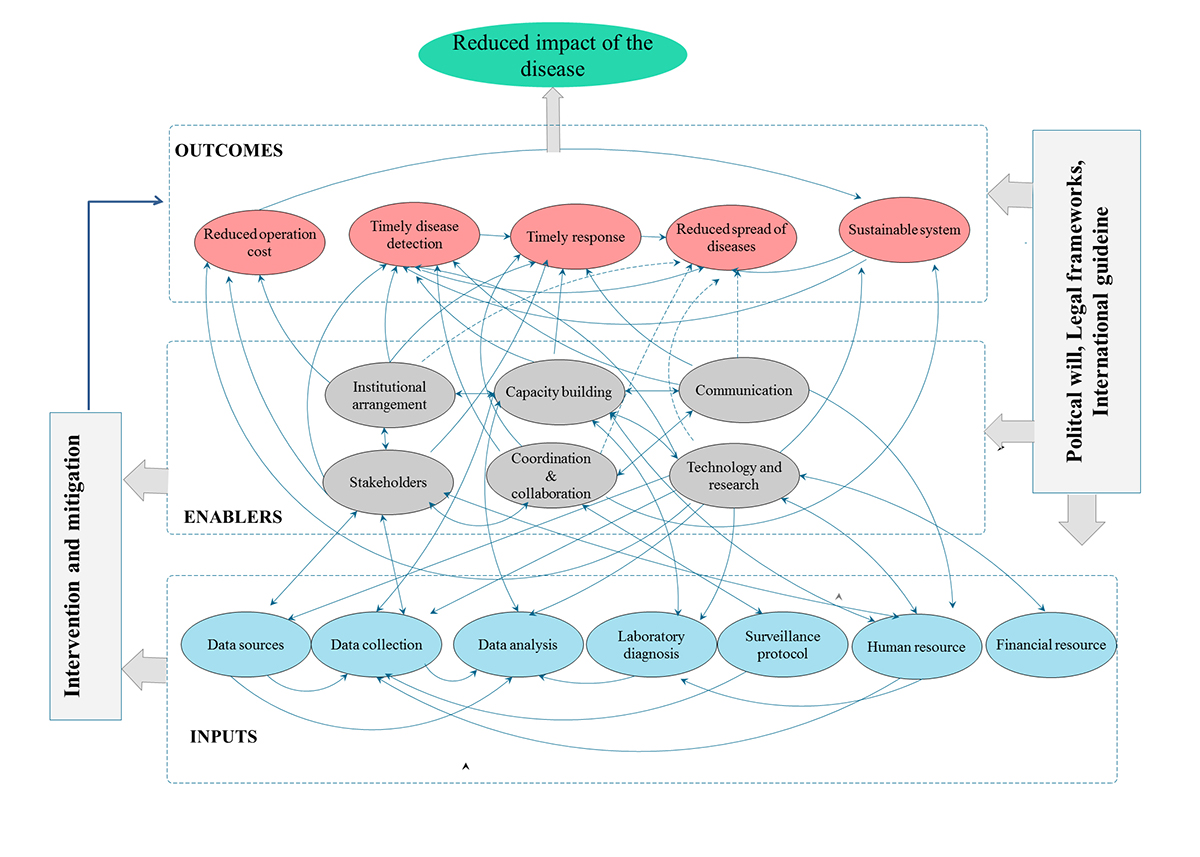

This study conceptualised animal health surveillance as a complex adaptive system that operates on open system principles (Figure 1). The system comprises a set of interrelated agents (inputs, enablers and outcomes) that interact with each other and the environment where the system operates (political will, legal framework and international guidelines). The agents are also sub-systems with their own interactions while forming part of the larger system. The adaptive nature of the system is due to the dynamic interactions between the agents and interaction between the agents and their external environment (Berezowski et al., 2019) and can evolve in response to the needs of its surroundings (Sturmberg and Bircher, 2019). Understanding animal health surveillance using a systems lens helps to identify critical and leverage points for system performance.

Stakeholder engagement in animal health surveillance

Stakeholder mapping was conducted in three districts (Sumbawanga, Tabora and Kilombero). This exercise revealed the level of interaction and influence of various stakeholders in animal health activities of which surveillance was a part. Various

stakeholders play different roles and apart from government stakeholders, animal health practitioners were found to collaborate closely with the private sector/NGOs and communities. The mapping exercise demonstrated that the system could benefit from diverse interaction and influence of various stakeholders, such as resource mobilisation and expanding the horizon of the surveillance data source (George et al., 2021).

Integrating animal health services at veterinary facilities

The study found that there were a lot of existing and potential surveillance data sources, but very few were actively used with limited integration. One of the recommendations was to integrate animal health services at the veterinary facilities to improve the efficiency of the surveillance system in early disease detection while also reducing the associated costs. For instance, the integration of veterinary services at the dip sites may help to motivate more people to use the services, while generating surveillance data through screening. Such an approach would reduce the cost of surveillance, as the overall cost would be shared with the cost for acaricides, dipping and accessibility of water (George et al., 2021)

Leveraging technologies to integrate animal health surveillance system

The world is heading towards big data and artificial intelligence for finding solutions for ever-pressing human challenges, including human and animal disease detection and prediction. This study showcased the integration of animal health surveillance systems by taking advantage of the existing technological innovations, such as AfyaData, SILAB-LIMS and EMPRES-I to design a prototype of an integrated surveillance system branded Wanyama2 HeAlth SuRveillaNce (WARN). It has demonstrated the possibility of having an integrated multi-data source animal health surveillance system. The prototype of an interoperable animal health surveillance system in Tanzania (WARN) is flexible and adaptable beyond animal health, hence providing more opportunities for One Health surveillance.

Such integration of data and analysis also facilitates the exchange of animal health data with the Public Health and other sectors in a coordinated One Health early warning system. This is being coordinated in Tanzania through the inter-sectoral National One Health Platform, coordinated by the Office of the Prime Minister.

Conclusion

Animal health surveillance systems are complex, and their analyses require a systems lens and integrative solutions, therefore, its analysis should not be done in isolation rather as part of the larger systems. Such integrated approaches are likely to be expanded in the One Health context to improve multi-sectoral One Health-based early warning.

Footnotes

- One Health has recently been re-defined in a Joint Statement by FAO, OIE, WHO plus UNEP as “an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimise the health of people, animals and ecosystems” https://www.fao.org/3/cb7869en/cb7869en.pdf

- Wanyama is a Kiswahili word for animals

References

- Berezowski, J., Rüegg, S. R. and Faverjon, C. (2019). Complex system approaches for animal health surveillance. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6(153): 1 – 11.

- George J, Häsler B, Komba EVG, Sindato C, Rweyemamu M, Kimera SI, Mlangwa JED. Leveraging Sub-national Collaboration and Influence for Improving Animal Health Surveillance and Response: A Stakeholder Mapping in Tanzania. Front Vet Sci. 2021 Dec 13;8:738888. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.738888.

- George J, Häsler B, Komba E, Sindato C, Rweyemamu M, Mlangwa J. Towards an integrated animal health surveillance system in Tanzania: making better use of existing and potential data sources for early warning surveillance. BMC Vet Res. 2021 Mar 6;17(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s12917-021-02789-x.

- Sturmberg, J. P. and Bircher, J. (2019). Better and fulfilling healthcare at lower costs: The need to manage health systems as complex adaptive systems. F1000Research 8(789): 1 – 13.

Author’s acknowledgements

This article is based on a research study conducted by Janeth George as part of her PhD programme under the auspices of the SACIDS Foundation for One Health. The author would like to thank Tanzania’s Director of Veterinary Services, Prof Hezron Nonga, National Epidemiologist Dr Ramadhani Makungu, Officers in-charge of zonal veterinary services and district council staff for their support during data collection. The author is grateful for the constructive feedback and inputs received from supervisors and mentors Profs Sharadhuli Kimera, James D. Mlangwa, Mark Rweyemamu, Erick Komba, and Drs Barbara Häsler and Calvin Sindato. The study also benefited from inputs from Tanzania Veterinary Laboratory Agency (TVLA) and Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO-Tanzania).

About SACIDS for One Health

The SACIDS Foundation for One Health (SACIDS) is a ONE HEALTH Virtual Institute that links academic and research institutions in Southern and Eastern Africa, which deal with infectious diseases of humans and animals within the African Ecosystem, in an innovative South-South-North smart partnership with world-renowned centres of research and training. For details visit www.sacids.org

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.