While cities only occupy around 3% of the Earth, they are where 50% of the world’s population live – but they are not usually included in global climate calculations, meaning that urban environmental problems can slip under the radar

Currently, half of the world are living in cities. From Wuhan to Manchester or Manhattan to Sylhet, each city is as unique and complex as the next. Scientists behind this new research say that increasing heat stress, water scarcity, air pollution and energy insecurity are a few of the problems that hit urban environments harder than rural ones. One disaster can reverberate across the ecosystem of a city and impact every last person.

In Flint, a city in Michigan, the 2014 water crisis hit residents with the unblinking ferocity of monsoon floods or sandstorms. The source of water was contaminated by a bad infrastructure decision, which led to individuals living with the knowledge that their drinking water contained high levels of lead. Despite the declaration of a State of Emergency in 2016 that saw the intervention of former President Barack Obama, this public health crisis is still ongoing – with 2,500 lead contaminated water pipes identified even in April, 2019. There are local doubts that even now – is the water is clean enough to drink without risking your health?

Discussing how contaminated water impacts whole ecosystems in first world countries, Environmental Health and Toxicology professor, Dr Elica M Moss said: “This concept is prevalent not only in Alabama and the United States, but anywhere in the world that may be vulnerable to atmospheric deposition from power plants and other industrial facilities.”

So, how does climate modelling relate to public health problems?

Currently, urban areas are being hit the hardest by infectious diseases like COVID-19, and air quality is killing people in cities like London – where pollution was legally ruled a factor in the death of Ella Kissi-Debrah, a young schoolgirl with severe asthma. The coroner said: “The whole of Ella’s life was lived in close proximity to highly polluting roads. I have no difficulty in concluding that her personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide and PM was very high.”

While global climate calculations and models are created to map the big picture, this means that cities can slide under the radar and be left out. A thousand situations like Ella’s are constantly fluctuating, quietly dependent on the ecosystem of the city around them.

This makes city inhabitants more vulnerable to unpredicted environmental health issues, which suffer the double-wound of not being mapped in the big picture assessments of climate change. These researchers are trying to figure out how can this information can be accurately incorporated into the global perspective.

This can be described as an “urban-to-global” information gap.

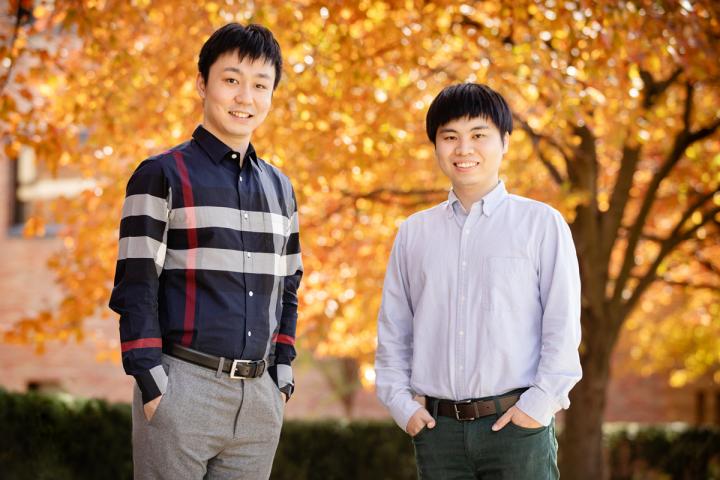

Researchers led by University of Illinois Urbana Champaign engineer, Lei Zhao, examined how climate change hits urban areas. They used data-driven statistical models in combination with traditional physical climate calculations. He said: “Cities are full of surfaces made from concrete and asphalt that absorb and retain more heat than natural surfaces and perturb other local-scale biophysical processes.

“Incorporating these types of small-scale variables into climate modeling is crucial for understanding future urban climate. However, finding a way to include them in global-scale models poses major resolution, scale and computational challenges.”

What did Zhao’s urban-focused climate model reveal?

The Zhao model predicts that by the end of the year 2100, average warming across global cities will increase by 1.9 degrees Celsius with intermediate emissions and 4.4 degrees Celsius with high emissions.

by the end of the year 2100, average warming across global cities will increase by 1.9 degrees Celsius

The findings also revealed a near-universal decrease in relative humidity in cities, making surface evaporation more efficient and implying that adaptation strategies like urban vegetation could be useful. The humidity of a city impacts the entire ecosystem, giving allergens a better environment to grow in and having the capacity to complicate respiratory diseases. Adding air pollution to the humidity creates a bad health environment for all those who spend long amounts of time in these places.

The cities of the world are going to have 70% of the world’s population by 2050. This is also the target year for several climate goals, like making the European Union carbon neutral. The research conducted by this team can create a better picture for how cities feed into huge regional goals that can change the course of the planet, while also creating a useful pool of information for local policy-makers and scientists.

“Our findings highlight the critical need for global projections of local urban climates for climate-sensitive urban areas,” Zhao said.

“This could give city planners the support they need to encourage solutions such as green infrastructure intervention to reduce urban heat stress on large scales.”