Inequality in educational systems is a complex issue based on interacting mechanisms, write Professor Dr Katharina Maag Merki and colleagues

The way educational systems and schools are organised is of pivotal importance, not only for the development of young people, but for providing equal educational opportunities for all pupils. However, we know that not all educational systems and not all schools are equally successful in supporting pupils in their development. Furthermore, in many countries pupils with a high socioeconomic family status outperform their counterparts significantly. But why is that the case? Is this because socially advantaged children are more intelligent or motivated than other children? Or are they better supported by their teachers and favoured by the educational system?

The grammar of inclusion and exclusion within educational systems

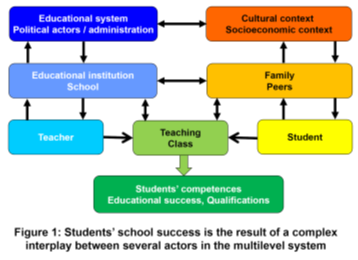

In our research project ‘KoS – Context-Oriented School Development’, we assume that there are certain mechanisms and processes in the educational system and schools that cause some pupils to be favoured while others are disadvantaged. By analogy with a language, which is based on a certain set of rules, e.g. those of syntax or semantics, we assume that those mechanisms do not occur randomly, but that they are equally governed by a system of rules. We call the sum of these mechanisms ‘grammar of inclusion and exclusion’. Based on empirical results, which kind of mechanism can be identified? Since the educational system is multilevel in nature, mechanisms at the system, school and teaching levels have to be differentiated (see figure 1).

Grouping pupils on secondary level one by several tracks:

Separating pupils into different tracks with different achievement requirements after primary school is one such mechanism. Due to special resources and interests of families, pupils from families with a high socioeconomic status can manage those transitions better than pupils from a lesser socioeconomic background. In educational systems without such transitions, therefore, the disadvantage for pupils is not as distinct.

Differential support strategies at school level:

In a system with strong vertical and horizontal stratification, the allocation of pupils in primary schools to school tracks with extended or basic requirements at secondary level starts early. Schools regulate who will get talented support or access to support strategies as a preparation for ‘gymnasium’ (highest level of requirements on secondary level one). In turn, pupils identified as low-achievers or labelled as pupils ‘in need’ are pre-selected for lower school tracks. This activates a mechanism of social closure and educationally handicaps these groups of pupils, because they don’t receive the relevant support for access to schools with extended requirements.

Grouping pupils within classes:

Also, on class levels, teachers often make decisions regarding single pupils while looking at more than just their abilities. When selecting adequate support measures for fostering pupils or when deciding on promotion of pupils at the end of the school year, teachers consider pupil’s familial background at the same time. Pupils who do not come from the ‘right’ families are often thought incapable of and discouraged from attending more demanding courses, even when in fact they would have the competences to do so.

Summary

The empirical results show that inequality in educational systems and schools is influenced by several factors. Findings showed that educational outcomes are not limited by pupils’ academic abilities or family educational aspirations alone, but are also influenced significantly by structures and processes within schools and school systems. This means that inequality in educational systems and schools is also ‘homemade’ and influenced by the school system, the schools, and the teachers themselves.

Considering this important result, it is obvious that educational institutions and teachers are responsible for adapting learning opportunities to pupils’ capacity for using them and to develop support strategies that help all pupils to achieve educational success.

Accordingly, the key determinant of high educational equality is how well educational systems are structured and how educators and teachers adapt their learning opportunities, curricula and resources within the educational system to each pupil’s specific requirements, abilities and family background.

Strategies to reduce educational inequality

Reducing educational inequality is very challenging, but is of high importance for modern society. Although the goal of decreasing educational inequality cannot be achieved by educators and teachers alone, there are several strategies that have the potential to reach the goal, particularly if the ‘grammar of inclusion and exclusion’ within educational systems is considered:

- Strong public educational systems with a wide range of educational opportunities for all pupils in order to provide all pupils ‘short distances’ to the next high quality and demanding school are very important in every society. If these distances are too great, socioeconomically or ethnically disadvantaged pupils will not have the resources or the skills to deal adequately with this challenging situation;

- The stronger the stratification system implemented in educational systems, the more important the family background for successful learning. Therefore, reducing vertical and horizontal stratification in school systems where students get selected at a young age for different tracks and providing a comprehensive educational system are important strategies to reduce educational inequality;

- Building up a high capacity for managing change on organisational, teacher and class level is a core requisite to improve school and teaching practices and processes;

- Implementation of sustainable co-operation between principal, teachers and further educational staff, and the reflection on support and selection practices within schools and classes;

- Critical analyses of grouping practices to foster pupils single classes and access to support measures;

- Continued professional learning of teachers helps to bring awareness to specific diagnosis, selection and grading biases.

Reducing educational inequality is hard work, takes time and requires shared responsibility between society, policy makers, school authorities, schools, and teachers. Therefore, teachers and educational staff in schools have only limited leeway to change practices if regulations, guidelines and rules at the system level hinder the implementation of more effective practices in schools that foster better equality between pupils. Without a joint effort, educational equality will not be easy to achieve.

Professor Dr Katharina Maag Merki

University of Zurich

kmaag@ife.uzh.ch

Dr Marcus Emmerich

University of Applied Sciences, Northwestern Switzerland

marcus.emmerich@fhnw.ch

Franziska Buehlmann

University of Zurich

fbuehlmann@ife.uzh.ch

Chantal Kamm

University of Zurich

chantal.kamm@ife.uzh.ch

http://www.ife.uzh.ch/en/research/teb.html

Please note: this is a commercial profile