Professor Emmanuel Frossard from ETH Zurich and his collaborators from Switzerland and West Africa experiment in the YAMSYS project, a novel approach for improved soil and crop management in yam systems

Whereas food insecurity has decreased in West Africa, it remains a major problem. Many projects aiming at improving agricultural productivity failed to deliver sustainable solutions because they were not sufficiently considering the needs and local knowledge of stakeholders. If we want to contribute to meeting the second sustainable development goal (zero hunger), we need to develop soil and crop management options which are not only relevant from a technical point of view but which also fit stakeholders’ needs.

The YAMSYS project addresses these issues in Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso using yam (Dioscorea spp) as a model crop. The project is conducted in an inter- and transdisciplinary manner by scientists from natural and social sciences from Switzerland and West Africa together with stakeholders from the studied sites. The following text explains the importance of yam and how YAMSYS will reach its aims.

The importance of yam for food security and challenges in yam production

The yam belt spanning from Cameroon to Côte d’Ivoire makes up about 90% of the world yam tuber production. Yam tuber provides 200 to 500 kcal per day per capita in the yam belt and is also a significant source of protein and micronutrients for human beings.

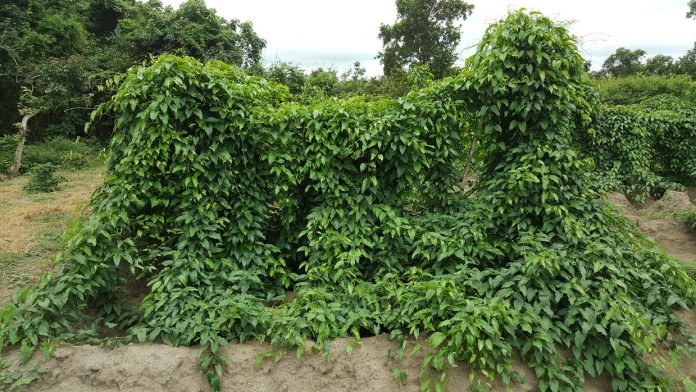

However, traditional yam cropping practices are not sustainable and farmers’ tuber yields are often lower than 10 tha-1. Yam is usually planted as the first crop after slash burning forests or long-term fallows leading to a decrease in biodiversity. Yam is seldom fertilised, leading to nutrient mining. Farmers use a large fraction of harvested tubers as planting material (yam seeds) for the next season, limiting the number of tubers that can be sold or eaten. These seeds are often infected by pests and diseases leading to bad germination and yield loss. The crop requires stakes to grow on which need to be taken from the remaining forests. Finally, post-harvest losses can be important due to inappropriate storage conditions.

In addition, yam production in West Africa is also affected by taboos. For instance, some people believe that women should no enter in yam fields at the risk of decreasing the production and women except widows should not own yam fields. Local knowledge is not always appropriate. Some farmers cannot recognise the white powdery mealybugs on yam tuber, a pest transferring diseases that spreads from plant to plant. They rather think that this shows the presence of potash, concluding that potash is dangerous for the plant.

Improving traditional yam cropping practices in West Africa requires an approach that includes stakeholders in the entire research process. To do so, YAMSYS developed innovation platforms, where stakeholders (yam producers, traders, transporters, researchers, extension agents, micro-finance institutions, political, administrative, traditional and religious authorities and the media) sit down and discuss together the problems of actual yam systems and how they can be solved.

YAMSYS approach

YAMSYS has deployed its activities since 2015 on four sites, located along a gradient ranging from the humid forest to the northern Guinean Savannah. Researchers started with a characterisation of the ecological and socio-economic diversity of yam systems at each site. The key stakeholders were identified to form innovation platforms at each site. These platforms met to identify and rank the bottlenecks to yam production. Options that could fix those bottlenecks were jointly developed and started to be tested in researchers’-managed trials. The results of these trials were discussed within the platforms. Farmers selected options and started to test them in their fields. Once proven efficient and acceptable by farmers, these options will be communicated to agricultural extension institutions for upscaling.

Preliminary results

The platforms prioritised actions on “clean seed”, fertilisation, planting density, optimised staking techniques, crop rotation and storage. “Clean seeds” are small tuber parts, treated with a cocktail of fungicides and ashes, allowing for optimal germination. In the researchers’-managed trials, we reached tuber yields up to 20 t ha-1 for D. rotundata in Côte d’Ivoire and only 12 t ha-1 in Burkina Faso. We reached tuber yields up to 35 t ha-1 for D. alata in Côte d’Ivoire and only 5 t ha-1 in Burkina Faso. In Burkina Faso low yields were due to difficult soil and climate conditions. The high yields were due to the use of “clean seeds” of improved varieties and nutrient inputs and to the regular plantation density.

In the farmers’-managed fields, farmers multiplied their tuber yields up to two times with the options proposed by the platforms. Socio-economic research is now undertaken to analyse the profitability and the adoption potential of these options. The long-term effects of the options on soil properties also need to be clarified. Training and communication materials for the dissemination of the options are being prepared and will be transferred to agricultural extension agencies. Upscaling has begun since an Ivorian institution already requested YAMSYS to develop innovation platforms on yam and to test the developed options in other yam growing areas of the country.

Lessons learnt

It was essential to fully include the stakeholders in the research process, otherwise any attempt to promote best practices would have been doomed to failure. Involving sceptic farmers was important, as once they were convinced, they became the best possible project ambassadors. Including stakeholders not directly concerned by yam, such as security forces, the microfinance sector and the media was equally important, as they facilitated the implementation and the acceptance of the project. The capacity building of farmers, extension agents and students and communication efforts were all indispensable.

Researchers needed patience, as stakeholders needed time to accept new things, which were sometimes contrary to their own local knowledge. The communication with agricultural extension agencies and national policy-making bodies needs now to be further developed. Finally, we believe that the approach developed by YAMSYS could be applied to other production systems, for much improved agricultural productivity in West Africa.

Please note: this is a commercial profile

Professor Emmanuel Frossard

ETH ZURICH

Tel: +41 52 354 91 40