The MHINT team has developed a fully open access operationally defined manual and observer syntax coding scheme in Observer XT and micro-coding scheme syntax

Humans are sophisticated decoders of human behaviour through micro-coding. At any one time we simultaneously process and face, movement, position, audio and much more information from those around us. With this we rapidly, and effortlessly, compute our interpretation and respond. We have no idea what we are computing.

Take the reaction to a goal. Just by watching the reaction, we know a goal has been scored and which team it belongs to. In this case, it’s movement, synchronised movement that tells us that; facial expressions and vocalisations confirm it.

As it’s so effortless and unconscious it can be hard to understand the under-lying components of behaviour that are important or how they are interpreted by others. Understanding is key when subtle changes in our behaviour can make important differences to our relationships.

Parenting research in parent-child interaction

In parenting research, the concept of parental ‘sensitivity’ is well known and is predictive of future positive child outcomes. Given that even for psychology researchers, it requires specific and time-consuming training to be able to assess reliably, for parents themselves such concept is somewhat opaque and unachievable and thus not be helpful if they want to improve their relationships.

Every parent-child interaction has strengths, further understanding of the building blocks of varied interactions will facilitate learning. Understanding the behaviours that precede desirable or less desirable target behaviours can aid understanding and behaviour change in more person-centred and strengths-based parenting support.

We have developed a fully open access operationally defined manual and observer syntax coding scheme in Observer XT.

Micro-coding to capture subtle behaviour

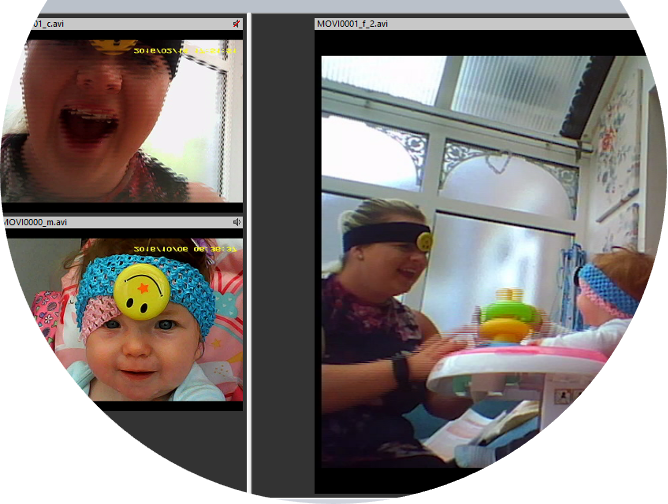

This coding scheme aims to capture as many relevant behaviours as possible, with the underlying hypothesis that individual differences in behaviours can occur subtly and that micro- behaviours provide specific targets for person-centred, strengths-based parenting support. The work, funded by the ERC, took five years and several researchers contributed to the process in an iterative process using existing coding schemes in the literature, applying to real data and going back to the coding scheme until everything observed could be captured.

This resulted in 27 behavioural groups with up to 12 options, 38 modifiers (subcategories within behavioural groups such as within speech the tone of voice), with up to five options. At any one time, both members of the interaction will be coded within each 27 behavioural domains. Even without modifiers, that results in a minimum of 729 possible combinations of dyadic behaviour at any one time. Not to mention the role of the preceding and following behaviours.

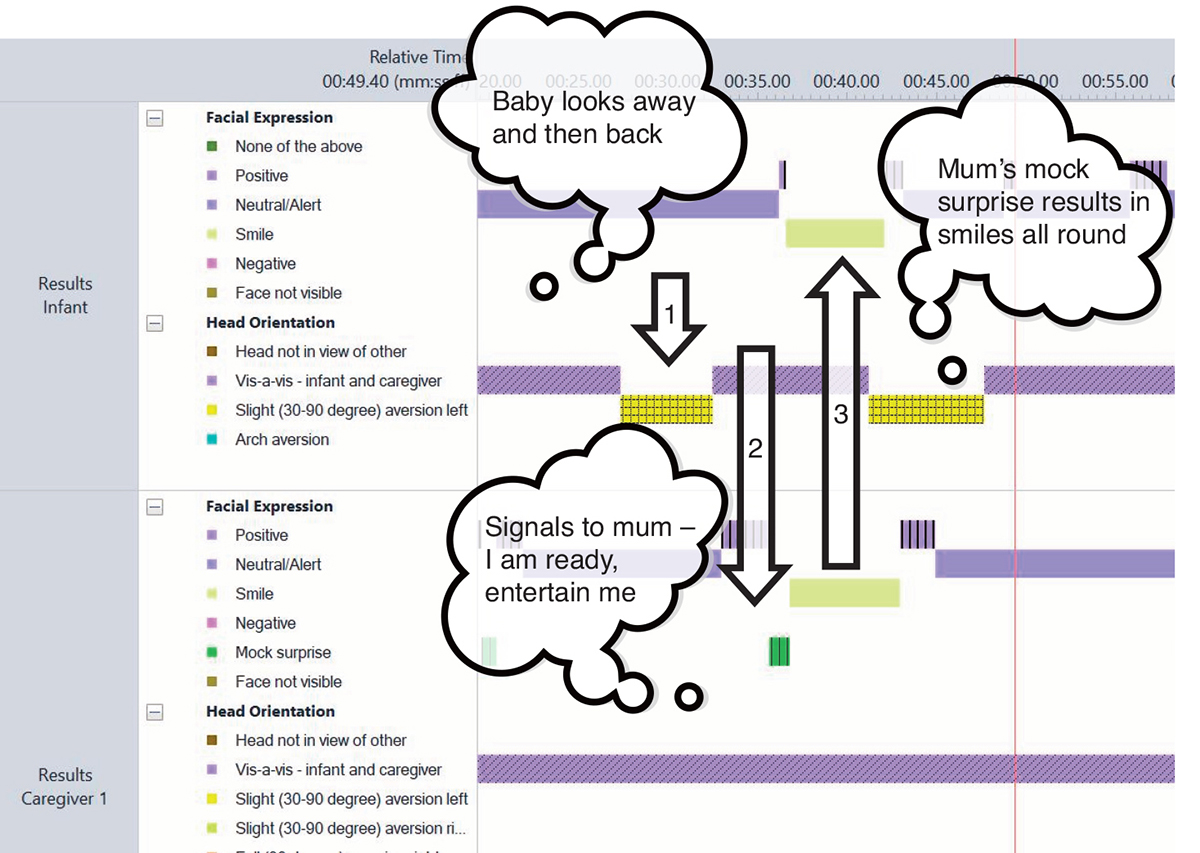

The visualisation of just two domains of behaviour, in the figure to the left, for 30 seconds, we learn so much. We can see here what drives the interaction, how the baby ‘instructs’ the mum to repeat a game of mock surprise and re-enforces the mums attempts with a smile.

Current work on micro-coding behaviours

Our ongoing work is exploring how the micro-coded interaction behaviours map on to the global constructs such as parental “sensitivity” using both mother infant moment by moment behaviours, importantly across behavioural domains (ie mirroring of facial expressions, as well as vocalisations or across behaviours where the affect tone is matched in face in mum and vocal in baby), and with quantification of duration of behaviours and time between behaviours.

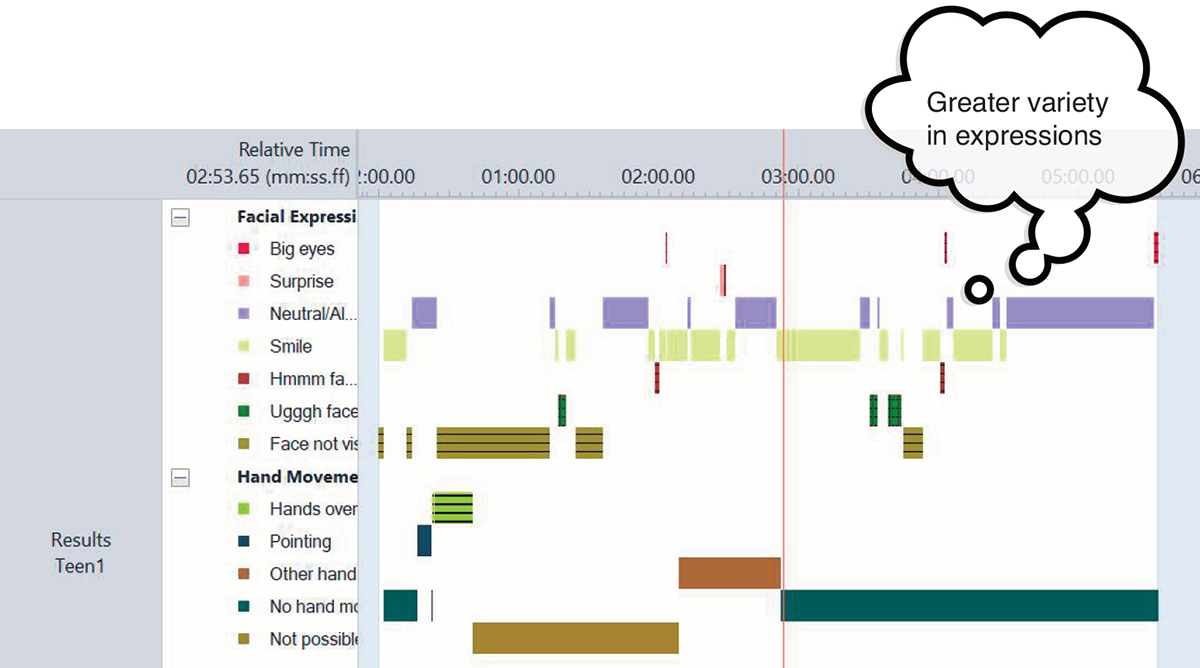

Current work is also ongoing to adapt our coding scheme to teenagers.

Interestingly, in infancy-specific facial expressions are used ‘Mock Surprise’. In our manual defined as “a surprised facial expression which does not represent an actual surprise. Mouth is open and eyebrows are slightly or evidently raised (Beebe et al, 2016). It usually occurs in playful interactions as ‘peekaboo’, example above.”

Mock surprise is very commonly occurring in our data, with 67 % of five-minute mother-infant interactions including a mock surprise face.

No doubt there are specific examples of adolescent faces. In our initial work with A-level Psychology students, we utilised the current teen vocabulary in the form of emojis and well-known text speak including ‘Big eyes/Rolling eyes’🙄, ‘hmmm/thinking’🤔, ‘eek’😬 and hand gestures such as a fist pump👊.

Initial coding of teenager behaviour (see figure below) demonstrates the greater variety of emotional expressions than infants and some initial demonstrations of so-called ‘teen emotions’ and hand gestures.

The MHINT team has provided training for teams internationally, please contact the research team, a brief video showing the coding scheme is below:

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.