Robin Stern, Chair at Future Perfect (Healthcare), discusses how patient journeys currently reflect a national ‘illness’ service, not a national health service

The journey a patient takes is in theory a simple, step-by-step process. It begins when a patient feels unwell. They go to their GP, the GP requests some tests, and the results may trigger a referral to a specialist. More tests, maybe an admission to hospital for a procedure, more outpatient appointments, and then social care to ensure a safe discharge along with ongoing community care. When no more care is needed, the journey ends – until the next problem arises.

A type of journey that reflects failed care and is reflective of a national illness service, not a national health service. Reactive, instead of pre-emptive. It also reflects the traditional ‘passive patient’ model, not that of an active, engaged one. It waits for problems to appear before action is taken. It doesn’t make use of the active, digitally enabled patient. So how can we change course?

To start with, we have to think of the journey in terms of the patient themselves, not in relation to their condition. Patients are individuals with medical histories that spread across decades of life and multiple locations, and sharing access to that medical history will allow for the preventative care that they should get.

Barriers to prevention over cure

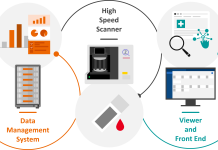

The healthcare system presently operates in silos and the electronic records systems that support that care are reflected in analogous data silos. Efforts are underway to start to build electronic records that illuminate the patient’s full history and show us a patient’s journey spanning past, present, and future. These efforts can indeed catalyse tackling the myriad of challenges the healthcare system faces if it is to turn towards forward-thinking, preventative care.

However, there are systemic, commercial self-interest and NHS internal market financial barriers to breaking down the data silos. Technical limits are imposed by vendors who decline to adhere to open standards, having the effect of placing a huge cost on liberating our data from their siloed systems. Some behave commercially as if they believe that this data belongs to them.

Secondly, the economics of pathway reform can be complicated. Consider patients using specialist services whose records never get joined up with their local ones – yet, this is all about the same patient journey and it remains all fragmented.

Thirdly, regarding the NHS internal market, a positive transformation to an end-to-end pathway might offer better care and be economically attractive overall, but actually be unattractive to the separate agencies that play a part in it, especially when their part remains unseen by the other players. For local commissioners, redistribution of money across the pathway is unaffordable, because many current contracts restrict change and, simply, it just isn’t worth it for them. Add into the mix: just when you think you’ve illuminated a whole patient journey, you discover other bits to it, for example, undisclosed by specialist commissioners to local ones.

For such a system to change, barriers remain rife. After all, people’s health and well-being journeys are indeed complicated. They don’t walk predictably from one service to the next in the same locality for their whole lives. Person-based illness prevention is already known to be investible, and pursuing prevention by leveraging joined-up records could offer so much more – and this could be an entirely different story.

Empowering the patient to prevent illness

So how do we make these fundamental shifts? I believe we can look to digital solutions to empower patients to make use of services that prevent illness. Enabling active patients through the use of apps that integrate and become part of the record of the patient’s journey, would allow them to manage their own care to a far greater degree, spotting problems sooner, and preventing crisis – in partnership with their GPs and more accessible specialists.

For example, for the management of asthma, there are apps which can be used to monitor a patient’s peak flow readings and relieve inhaler usage day-to-day, issuing alerts when the patient is at risk of an attack. There is AI that can ‘learn’ about the patient and advise on urgency, offer predictions and build up observations to communicate with clinicians on an exception-reporting basis. The effect can be lifesaving, and reflective of a true ‘health’ service as opposed to an ‘illness’ service, which might not treat the patient until an attack occurs.

These apps could become a staple part of the patient journey that often traverses beyond the pathway of any one particular condition. This would allow both patient and clinicians to have a view of the patient’s history to date and, also, keep an eye on the future. The apps could be prescribed. People are complex and have many differing needs, their healthcare system needs to reflect that – and fully integrated longitudinal records with such patient participation would be the backbone of a true National Health Service.

Future vision of population health management

Take public healthcare, and apply it to person-based illness prevention. Organise and synergise existing collection systems and apply the data to the person. It changes the dynamic of the patient journey from being focused on the extremes of acute illness to being about health – the whole cycle. There are so many examples you can think of where this might work, from asthma to diabetes, and we need investment in this area to make it happen.

That’s a true National Health Service.