The Climate Hazards Group contributes to Food Security Outlooks that strengthen food security

The Climate Hazards Group (CHG) brings together a cooperative team of multidisciplinary scientists and food security analysts from the University of California, Santa Barbara, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Africa and Central America to develop data sets, tools and forecasts that help guide effective disaster responses and long-term development plans in food-insecure countries.

Working closely with partners in the USGS, NOAA CPC, NOAA ESRL, NASA, USDA and the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), the team uses climate and hydrologic models together with satellite-based Earth observations to provide six-to-eight month food security outlooks for the world’s most vulnerable populations. The CHG supports critical planning and timely humanitarian assistance that ultimately saves lives and livelihoods.

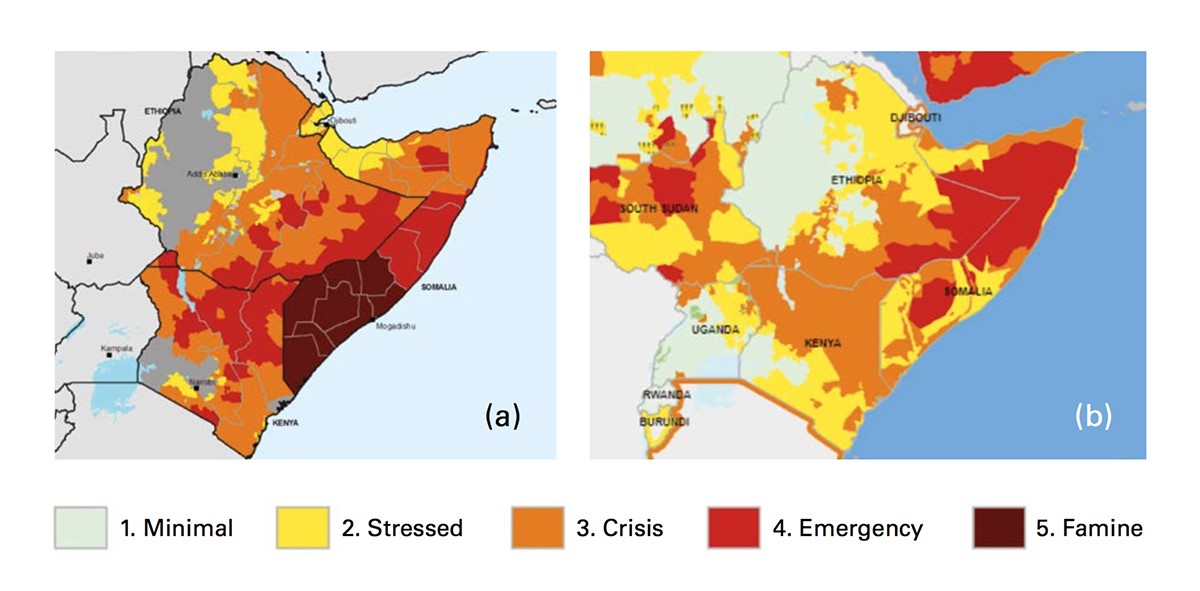

When climate variability and shifting climatic trends converge to produce severe droughts, fragile food insecure populations may face rapid-onset food crises as resources diminish, prices rise and household incomes decline. In vulnerable areas, these unanticipated climate shocks may devastate herds and harvests and degrade local food stocks. Unfortunately, the number of very hungry people continues to grow at an alarming rate over the past few decades, with more than 76 million people experiencing life-threatening conditions in 2017 and 2018.

Many of these extremely food insecure people live in Africa, which experienced a recent sequence of severe droughts associated with an extreme El Niño and La Niña. To monitor these droughts, the CHG has developed the Climate Hazard Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data (CHIRPS) data product.

CHIRPS harnesses the power of satellite technology, which is able to provide regular, detailed observations of entire regions. With each pass of the satellite, observers gain comprehensive information about how precipitation interacts with the geography. When combined with station data, CHIRPS allows for the rapid identification of hydrologic extremes, such as the terrible El Niño-related droughts in Ethiopia and Southern Africa in 2015-16, or the La Niña-related droughts in East Africa in 2016-2017.

Recent research (a, b, c) by the CHG has linked these droughts to very warm sea surface temperatures in the eastern and western Pacific Ocean. Very warm east Pacific waters (associated with the 2015-16 El Niño) contributed to rainfall deficits and very poor growing seasons in Ethiopia and Southern Africa.

In 2016, the global climate transitioned to a La Niña event, presenting cool east Pacific conditions and very warm waters in the western Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean – perfect conditions for producing back-to-back droughts in Kenya, Somalia and eastern Ethiopia. Recognition of the dangers posed by these warmer waters helped the CHG and partners effectively predict droughts (d) in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

The CHG team has helped document predictable sequences in these extremes (a). Several times over the past twenty years, a strong El Niño has occurred, followed by a La Niña. In 1997-2001, 2008-2011, and 2015-2017, successive El Niños and La Niñas produced multi-year increases in drought and food insecurity. These insights have helped FEWS NET, working with its network partners, successfully provide “food-security early-warning advisories with a six-to-eight months month lead-time (d).”

In 2010-11, such a pattern contributed to a very intense drought over Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya, with more than 12 million people requiring assistance. Sadly, in Somalia, a combination of armed conflict and poor food access and availability led to the deaths of more than 250,000 people.

In October of 2016, the CHG began providing advance warning of another similar drought for East Africa. By June 2017, 27 million East Africans required urgent food assistance. This drought led to a United Nations appeal for $4.4 billion in funding – twice the amount requested in 2011.

Indeed, “the improved early-warning systems and multi-agency responses employed during this drought, as well as improved humanitarian access thanks to less-adverse patterns of conflict, meant that famine was averted, unlike the case in 2010-2011 in Somalia” (d).

In 2011, Somalia food prices reached catastrophic levels. In 2017, the timely arrival of aid helped stave off meteoric increases, averting famine (Figure 1).

The CHG and FEWS NET partners also helped provide early warning for the 2015-16 drought in Southern Africa. Predictions for a strong El Niño led to pessimistic food-security outlooks beginning in July of 2015. By January 2016, nearly five months before the end-of-season crop harvests, analyses of seasonal rainfall to date and historical El Niño rainfall performance led to a consensus FEWS NET agro-climatological assumption that crop performance in most Southern Africa countries was likely to fall below average. By June of 2016, the early warning community estimated that some 40 million people in the region needed humanitarian assistance.

Communication, collaboration, capacity

These early warning successes have made an important contribution to the implementation of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly to Goal 2 and the challenge of ending hunger and achieving food security for all.

Close working relationship between climate scientists and food security analysts have enabled scientists to respond to the analytical needs of food security experts. These effective communication systems have facilitated the production of well-targeted briefs, reports and web-based interventions delivered to high-level decision-makers in both donor countries and organisations, and in the affected countries.

A unique and valuable component of the CHG team is its international composition (Figure 2). Almost half of the members of the CHG team live in Africa or Latin America. These scientists work closely with local stakeholders, decision-makers and science institutions to increase disaster preparedness and guide long-term “climate-smart” development. Building on the CHG’s commitment to developing data sets and tools, as well as harnessing the tremendous potential of satellite-based Earth observations, these capacity-building efforts are strengthening defences along the frontlines of climate variation and change.

Dr Chris Funk

Department of Geography

Tel: +1 805 893 4223

http://chg.geog.ucsb.edu/people/chris-funk/

Please note: this is a commercial profile.