Winy Vasquez, Faculty of Forestry, University of British Columbia, with Terry Sunderland, shed light on conservation and the right to food

“Every man, woman and child has the inalienable right to be free from hunger and malnutrition in order to develop fully and maintain their physical and mental faculties” UN General Assembly, 1974.

Almost 50 years have passed since the 1974 World Food Conference that laid out the groundwork for the right to food. While some progress has been made since then, we are still grappling with large scale food insecurity and malnutrition. The Food and Agricultural Organization’s most recent report on The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, estimates that 690 million people across the world are experiencing hunger and despite efforts to decrease these numbers, the number of people affected by hunger has been on the rise since 2014. At the same time, we are facing a global environmental crisis that has seen unprecedented levels of bio-diversity loss, species extinction and land degradation, all of which negatively impact food security and livelihoods.

As the realities of climate change are beginning to be felt, usually by the poorest and most disenfranchised communities first, the call for increasing protected areas has been on the rise. Multiple conservation strategies have been proposed to curb the loss of biodiversity, but none have been stronger than the calls to increase the extent of both marine and terrestrial protected areas in an effort to conserve critical ecosystems and slow climate change.

However, the dominant paradigm of biodiversity conservation, rooted in erroneous notions of pristine wilderness, has made it possible to separate humans and nature and at its extreme, has pitted one against the other, to the detriment of both the people and the planet. While the importance of protecting biodiversity and ecosystem services cannot be understated, how protected areas are imposed and managed should be revisited and reworked to break away from a legacy of “fortress conservation” that can lead to displacement, infringement of rights, loss of access and other negative social impacts. In contrast to the Western protected area model, many Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, who have been able to retain their traditional knowledge and practices have been able to maintain biodiversity at levels that have rivalled that of protected areas, whilst also supporting healthy, diverse, and nutritious diets. Ultimately, biodiversity conservation and healthy livelihoods, including the right to food, do not have to be mutually exclusive.

How forests contribute to food security

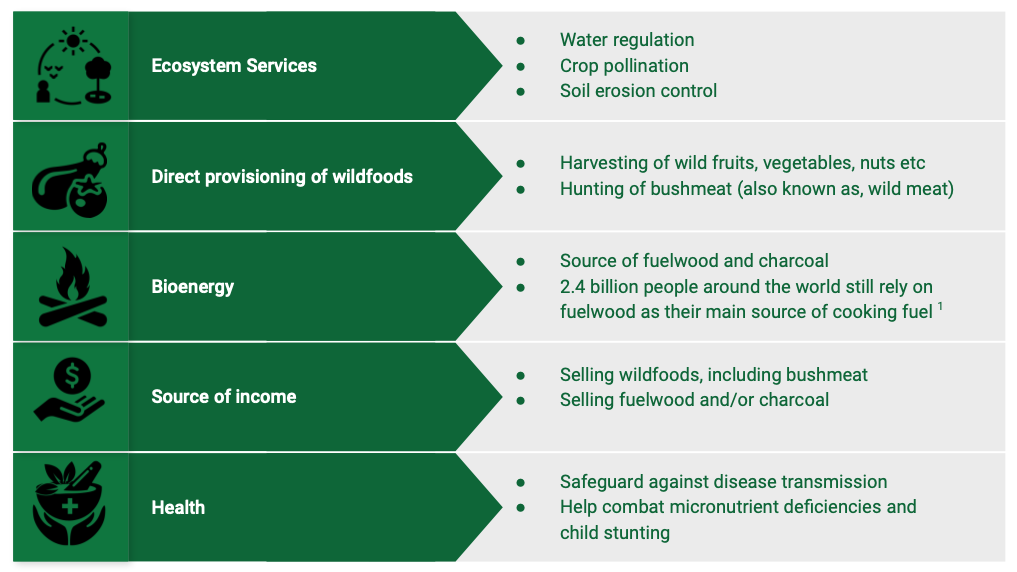

For much of human history, forests have been helping to sustain healthy and nutritious diets directly through the direct provisioning of wild foods and indirectly through ecosystem services such as pollination, water regulation and soil stabilisation [Figure 1]. As protected areas have been established globally to protect biodiversity, the communities who previously relied on these landscapes have often have to bear the consequences that come with the separation of people from the land and resources that sustain them, both physically and culturally.

Forests and tree-based landscapes play a fundamental role in supporting diverse, nutritious and sustainable diets, an increasingly important issue in the face of climate change. As communities who previously had rich and diverse local food systems have been excluded from their traditional lands and resources, many communities have experienced a nutritional transition towards less healthy diets that rely on an increasingly narrower range of foods that are often high in fats, salts, sugars and carbohydrates. This nutrition transition has also led to an increase in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Aside from an increase in NCDs, a shift to poorer quality and less diverse diets has also had devastating lifelong consequences for infants and young children who can experience micro-nutrient deficiencies, anaemia and childhood stunting due to chronic malnutrition. One way to combat this is to supplement diets with wild foods, a common practice in many parts of the world. One comparative analysis of 24 developing countries, for example, found that 77% of households engaged in wild food collection and the diversity of the food harvested was more than double that of cultivated food crops, again proving the importance of rights and access in overall food security and nutrition.

Looking forward

As the importance of the intricate link between forests and people are becoming undeniable, we must re-centre conservation efforts so that they support both the people and the planet. One way in which we can attain biodiversity conservation while supporting more diverse and nutritious diets, particularly for forest-dependent communities, is through increased recognition of the importance of wild foods coupled with rights and access to them.

Conservation and food security goals can be simultaneously achieved when management and implementation decisions integrate the fundamental right to food. By supporting local food systems through food policies that are grounded in a rights-based framework, it will be possible to support sustainable practices that lead to healthy diets that are supported by and thus safeguard local biodiversity.

The promotion of local food systems based on access to conservation areas coupled with the increased recognition of the importance of wild foods will also translate to more diverse diets that are not only more sustainable than their monoculture agricultural counterparts but are also more resilient in the face of climate change. This paradigm shift, from fortress conservation to more holistic conservation mechanisms that honour and respect a plurality of perspectives and knowledge systems, can lead to substantial changes in human well-being and conservation.

A re-thinking of conservation policies to include the right to food will go a long way in increasing food security while safeguarding biodiversity but it will not be the only way forward. Rights-based approaches in conservation must work in conjunction with other initiatives at different scales to continue to combat malnutrition and food insecurity while protecting the biodiversity on which we all depend.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.