Byron R. Johnson and Sung Joon Jang from the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University explore the correlation between religious involvement and human flourishing for those in offender rehabilitation

An epidemic began in the U.S. in the mid-1990s and continues to escalate to the present. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that the year 2020 witnessed ninety-three thousand drug overdose deaths, a 30 percent increase from 2019 and the highest total ever recorded.

With the opioid crisis as the main driver, the number of drug overdose deaths has quadrupled since 1999. According to the CDC, the rate of suicide for those within the age category of 10 to 24, increased nearly 60 percent between 2007 and 2018. The CDC also reports that suicide is now the second leading cause of death among people ages 10-34. For males and females, alcohol-induced death rates have also increased dramatically between 2006 and 2018.

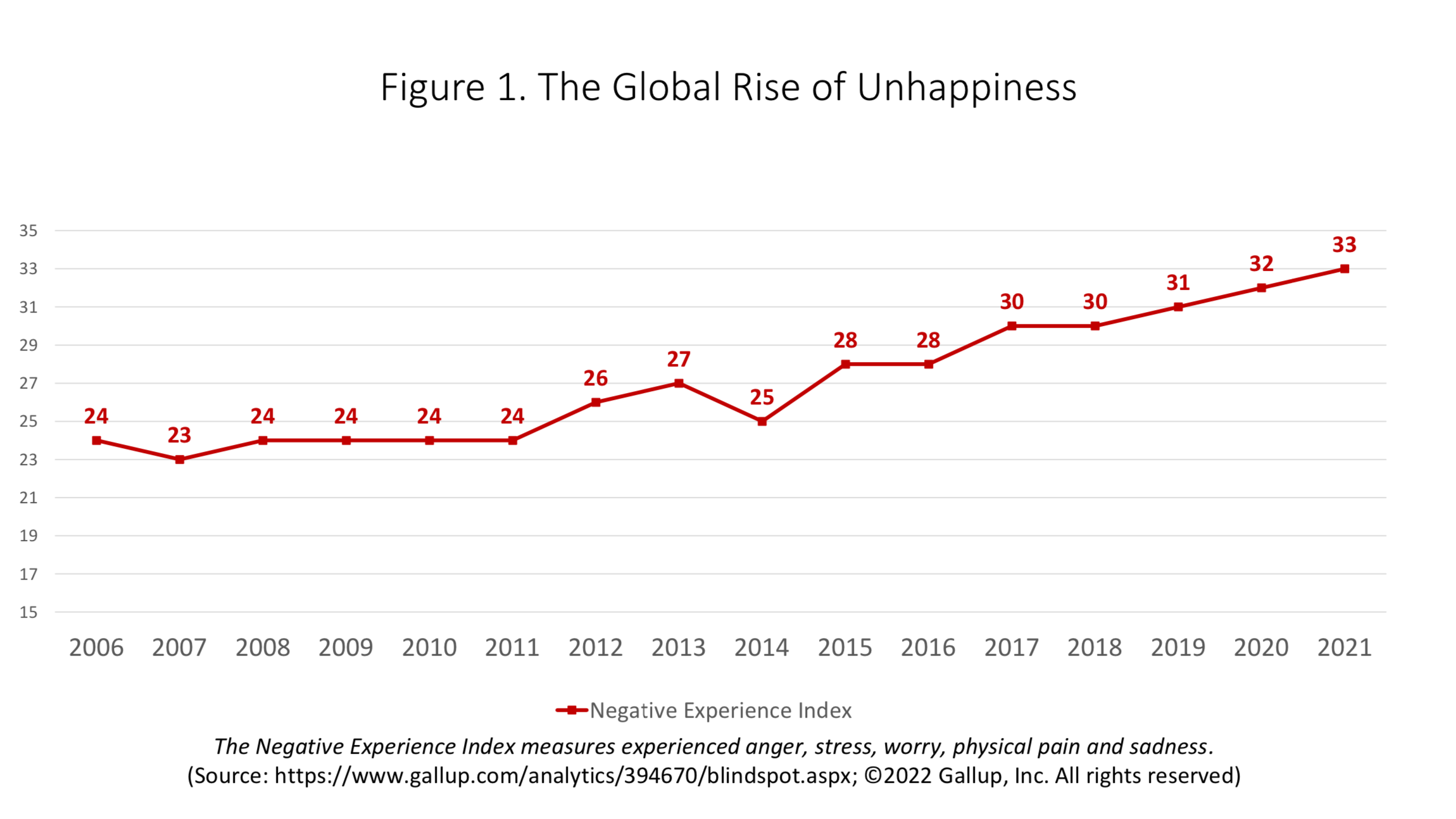

The lived experiences of people matter, especially in a world of well-being inequality, where some experience “diseases of deficiency” like homelessness and hunger, while others suffer with “diseases of excess” like obesity and alcoholism, often within the same society. According to Jon Clifton, Gallup CEO and author of the book, Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness, there has been an unprecedented rise of stress, anxiety, anger, pain, and suffering over the last 15 years in countries around the world (see Figure 1).

In addition, the Gallup World Poll reveals that less than a quarter of the earth’s human population is truly thriving. There has been much emphasis on understanding things like material prosperity, standard of living, Gross Domestic Product, and positive emotions. These indicators have been headed in a positive direction for a number of years. But negative emotions such as anger and loneliness are also rising dramatically over the last 15 years.

It has been argued that the rise of “deaths of despair” has been brought about by rapid social and economic changes (e.g., declining wages and poverty), which continue to loosen a previously tight cultural fabric. Relatedly, others suggest these deaths of despair are a response to a way of life, influenced by declines in wages, marriage rates, and civic engagement among less-educated citizens. Indeed, there is considerable agreement that the unraveling of key core values like care for neighbor, generosity, and accountability, as well as other markers of social cohesion like service to others and trust, have left many people experiencing anxiety, disorientation, hopelessness, and ultimately, despair.

Though economic turmoil is clearly a factor, it is impossible to explain these disturbing trends through measures of declining material advantage. Many people in America and the developed world who are better off economically, are at the same time are struggling with negative emotions. Conversely, many of the world’s poor and disadvantaged are not necessarily overwhelmed by suicide and various alcohol and substance use addictions. Many are becoming more miserable even as their standard of living continues to rise, in part because more attention has been directed towards a materialist conception of well-being, instead of a more holistic understanding of human flourishing. Recent holistic conceptualizations of flourishing have the potential to provide humanity with a better path forward.

We need to better understand why some report high levels of well-being and others report low levels of flourishing. Interestingly, the decline of religious involvement—a factor one might logically expect to affect negative emotions and even despair—receives relatively little attention as a possible cause for the global rise of unhappiness. This oversight is unfortunate, because there is ample empirical evidence of the important role that religious communities play in enhancing human flourishing. Moreover, there is a mounting body of research documenting that religious involvement, such as religious service attendance, contributes to a host of positive outcomes. These include overall flourishing and wellbeing, social integration and support, delivery of social services to disadvantaged populations, mental and physical health, happiness, forgiveness, philanthropy, generosity, volunteering, crime reduction, prisoner rehabilitation, healthy family functioning, lower rates of substance use/abuse, sobriety for addicts, health care utilization, coping strategies for stressful conditions, and even longevity/mortality.

Though it may be counterintuitive to many, it is hard to imagine a more effective and proven antidote to “deaths of despair” than regular religious service attendance and participation in religious communities. Harvard political scientist, Robert Putnam, who has studied the determinants of social capital for more than two decades, has demonstrated that fully half of all social capital in America is actually spiritual capital, and can be found within our houses of worship. Simply stated, regular religious service attenders are the beneficiaries of vast networks of social and spiritual support that help to explain the high degree of spiritual capital and good will that is produced within congregations. Through various teachings and a host of other-minded activities, religious communities are able to generate a powerful constellation of factors that protect adherents from depression, isolation, and stress, all of which contribute to deaths of despair.

Human Flourishing Approach to Offender Rehabilitation

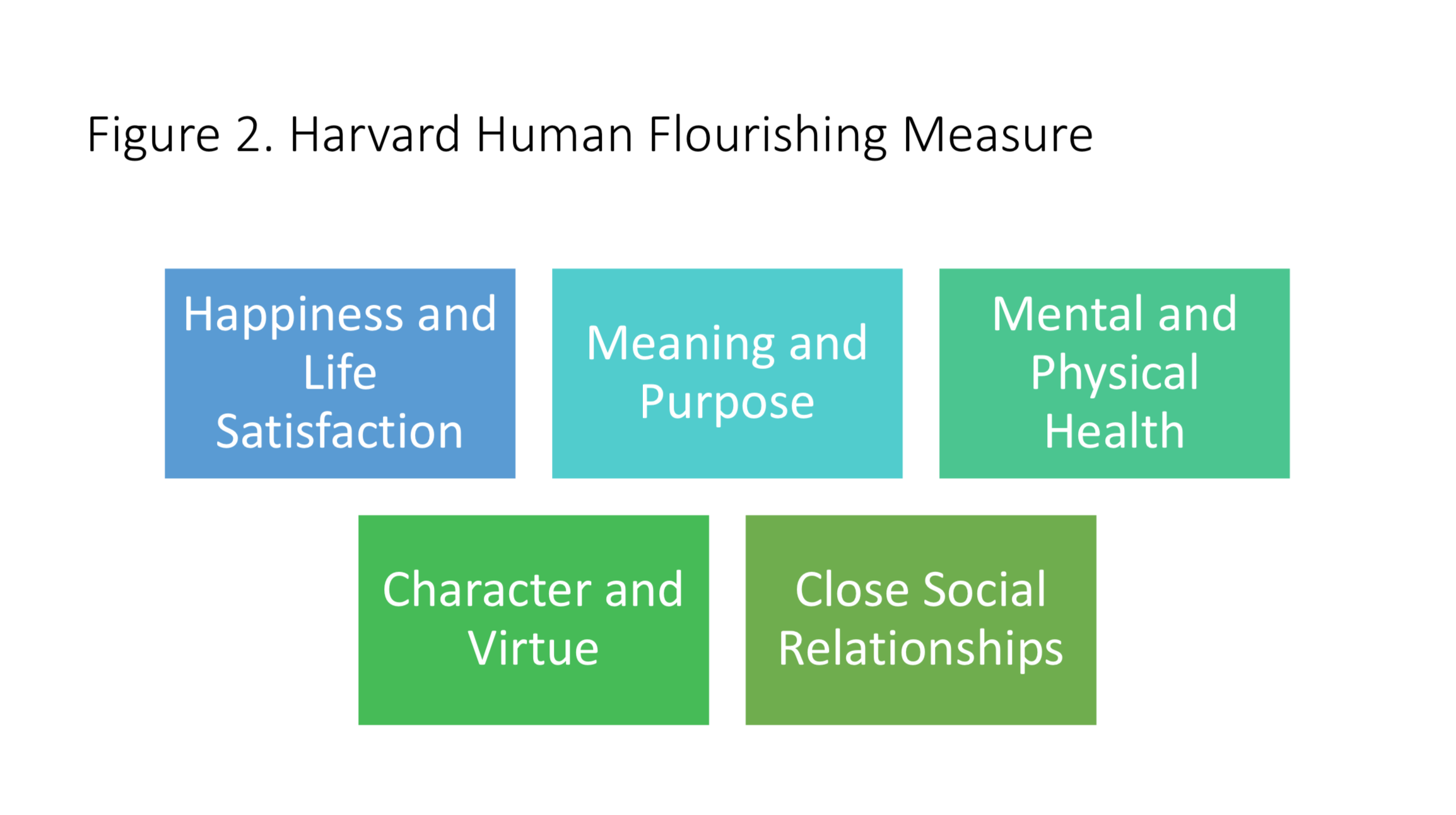

Human flourishing can be defined as “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good” and refers to “doing or being well in the…five broad domains of human life:” happiness and life satisfaction; health, both mental and physical; meaning and purpose; character and virtue; and close social relationships (see Figure 2).

Each domain tends to be viewed as an end in itself and nearly universally desired by humans. While VanderWeele uses the concept of human flourishing in the realm of epidemiology, it is applicable to criminology and criminal justice, as individuals low on flourishing in all or most domains of life are more likely to commit crime than those high on flourishing, thereby becoming subject to a response from criminal justice system.

To the extent that crime is attributable in part to a lack of flourishing, the concept is applicable to offender rehabilitation. For example, Ward and colleagues applied the idea of human flourishing to offender rehabilitation and developed the “Good Lives Model” (GLM), where their “primary human goods” overlap with VanderWeele’s life goals of human flourishing. Primary human goods are “actions, states of affairs, characteristics, experiences, and states of mind that are intrinsically beneficial to human beings and therefore sought for their own sake.”

The GLM posits that offenders as human beings that are goal-oriented live their lives to accomplish their life goals, which consist of at least ten groups of primary goods: (1) life (“healthy living and physical functioning”), (2) knowledge, (3) excellence in play and work, (4) autonomy, (5) inner peace, (6) relatedness (“warm, affectionate bonds with other people”), (7) community, (8) spirituality (“the desire to discover and attain a sense of meaning and purpose in life”), (9) happiness, and (10) creativity (“the desire for novelty and innovation in one’s life”). The GLM suggests that crime is a result of individuals lacking internal capabilities (e.g., social skills) and external conditions (e.g., employment opportunities) that are necessary to pursue primary goods, or a good life plan.

While these primary goods are all relevant to the etiology of offending—that is, failure to achieve them are likely to contribute to criminal behavior in varying degrees, we focus on two primary goods that we believe are relatively central to offender rehabilitation: autonomy and spirituality. We also discuss one of VanderWeele’s life goals of human flourishing, “character and virtue.”

Autonomy: Identity Transformation

The GLM’s emphasis on autonomy (i.e., agency and self-directedness) is related to criminal desistance theorists’ discussion of “critical events that create a sense of crisis in offenders and ultimately prompt them to re-evaluate their lives and reconstruct their identities.” These critical events are also called “hooks for change” (i.e., turning points) that are catalysts for cognitive and emotional transformations, which may result in a new identity. For Paternoster and Bushway, a key to identity transformation is the cognitive process of self-reevaluation—which Baumeister labeled “crystallization of discontent”—where offenders attribute their failures and dissatisfactions in life to their criminal identity, and are thereby motivated to engage in self-change.

The GLM process of helping offenders achieve the primary good of autonomy contributes to constructing their new identities. Research documents that desisting ex-offenders created a “redemption script,” where they found a way to “make sense” out of their past lives and even see redeeming value in lives of being in and out of prisons and jails. Offenders reinterpreted their negative past experiences as offering a pathway to create a new identity that engenders recovering a sense of agency and control over life, as well as discovering their “true self.” This process results in a desire to be productive and put negative experiences “to good use” by giving back to the community, as well as assisting others with the same problems with which they themselves have struggled. On the other hand, persistent active offenders lived their lives according to a “condemnation script,” whereby they see themselves as victims of deterministic forces and an impoverished sense of agency with very little chance of positive change.

Prior research provides empirical evidence that religion contributed to cognitive and emotional transformations and crystallization of discontent. Specifically, using survey data from more than 2,000 inmates at America’s largest maximum-security prison, the Louisiana State Penitentiary (a.k.a., “Angola”), it was found that a prisoner’s religious conversation was positively related to cognitive transformation and crystallization of discontent. Also reported was that prisoner involvement in religion was positively related to emotional transformation.

Spirituality: Meaning and Purpose in Life

Humans are existential beings in that they have an innate need for meaning in life, which Steger and colleagues defined as “the sense made of, and significance felt regarding, the nature of one’s being and existence.” Closely related to this concept is purpose—which refers to an intention, some function to be fulfilled, or goals to be achieved—as life’s meaning largely comes from having a goal (or goals) and striving to accomplish it. As humans, offenders have the innate need for meaning and purpose in life, although they may not have been conscious or aware of it except feeling empty inside or that something is missing in life. Thus, a crisis offenders have is likely to be in part existential, as offenders are confronted with the reality that their lives seem to have no meaning or purpose.

Lacking a sense of meaning and purpose in life is likely to lead one to engage in behaviors harmful not only to oneself (e.g., drug use or suicide) but also others (e.g., violence) because meaning or significance in life is closely related to the notion of morality: that is, what is right and wrong, good and bad, and just and unjust. This is why the GLM lists “spirituality”—which “refers to a desire to discover and attain a sense of meaning and purpose in life”—as a primary human good, which a rehabilitation program should help offenders with.

Although life’s meaning can be claimed based on anything, Frankl suggests that the “true meaning of life” should be self-transcendent (i.e., discovered outside of an individual). Thus, religion—which involves a transcendent being (e.g., God)—is a major source of meaning in life for many, though self-transcendent meaning may come from other sources than religion, such as patriotism or environmental care. In correctional institutions, religion is readily available to offer a time-honored system of meaning to offenders, helping them develop a new sense of meaning and purpose in life.

Prior research shows a positive relationship between religiosity and a sense of meaning and purpose in life among prisoners, as found among people in general populations. For example, Jang and colleagues found that religiosity was positively related to perceived meaning in life among males housed at three maximum-security prisons in Texas. This finding was replicated by a study of males and females confined in four correctional centers of South African: that is, more religious prisoners scored higher on a sense of meaning and purpose in life than their less or non-religious peers. This positive relationship was found among females as well as males, indicating that the relationship was general-neutral as well as cross-culturally applicable.

Character and Virtue: Virtue Development

There are two traditions in the study of well-being built around two distinct philosophies: one is hedonism, and the other is eudaimonism. Unlike the hedonic view, which defines well-being in terms of pleasure versus pain, the eudaimonic view equates well-being with eudaimonia (a Greek word that is composed by eu, “good,” and daimon, “indwelling spirit” or true self), which means the fulfilment of one’s true nature or a state of basic human needs being realized. For example, Aristotle argued that happiness is found when an individual acts according to virtue, because acting virtuously is one of the basic intrinsic needs of humans. For example, the GLM’s primary good of “happiness” refers to “a hedonic (pleasure) state or the overall experience of being content and satisfied with one’s life, and includes the sub-good of sexual pleasure.” While including this hedonic “happiness and life satisfaction” in his five life goals for human flourishing, VanderWeele also recognized “character and virtue”—a source of eudaimonic happiness—as an important life goal for well-being. We focus on character and virtue, as virtue development is a key component of offender rehabilitation as moral reform.

To the extent that crime is a result of limited moral capacities, rehabilitation as moral reform needs to aim at developing virtues among offenders. Since most religious traditions promote virtues, like forgiveness, gratitude, accountability, and self-control, offender’s involvement in religion is expected to enhance virtues. Religion not only emphasizes but also reveres virtues, teaching adherents to adopt and practice divine-like qualities. For example, in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, forgiveness is one way to imitate God who forgives; whereas in Hinduism and Buddhism, forgiveness is a way to avoid causing more suffering, both for oneself and others, in light of karma. In addition, religious communities strive to stimulate virtue development as they collectively engage in practices that promote the connection between a transcendental narrative and virtuous behavior.

Prior research provides empirical evidence that religion fosters virtues among individuals in the general population. Although research on the religion-virtue relationship among offenders has not often been conducted, Jang and colleagues found that more religious prisoners tended to score higher on the virtues of forgiveness, compassion, and gratitude than their less or non-religious peers. Positive relationships between prisoner religiosity and virtues (forgiveness, accountability, gratitude, and self-control) have also been replicated in a series of study conducted in Colombia and South Africa.

Religious Involvement is Linked to Factors That Lead to Human Flourishing

Religious involvement, such as regular church attendance, is linked to factors that lead to human flourishing. Based on numerous peer-reviewed publications, the main takeaway is that regular religious participation promotes individual health and wellbeing. In addition to the benefits to individuals, many congregations and faith-based organizations are on the front lines everyday working to address society’s more pressing social problems like alcohol and drug addiction, homelessness, crime, and foster care and adoption, to mention just a few. And recent scholarship now indicates that faith-based programs can even help those who are incarcerated to experience flourishing.

However, the opposite is also true—the absence of participation within religious communities is associated with an abundance of deficits including the inability to cope with various life stressors, lack of purpose, meaning, and hope, social isolation, narcissism, and depression. Research confirms that these deficits are inextricably linked to the dramatic rise in deaths of despair. In fact, new scholarship suggests that a decline in religiosity represents a public health crisis. Thankfully, the data are also quite clear that a powerful antidote to these deaths of despair is being an active participant in a vibrant religious community. The simple act of inviting people to houses of worship may be a critical first step in helping them to find social connectedness and support, a sense of belonging, meaning and purpose, and even accountability to God and others.

Since faith-based organizations and faith-motivated volunteers are ubiquitous in prisons, it makes sense that they would be an obvious candidate for meeting the non-criminogenic needs of offenders. Goods promotion is a natural by-product of the work of faith-based groups. Moreover, faith-motivated volunteers do not add financial burdens to already constricted correctional budgets, since religious organizations are willing to bring outside financial and human resources into prisons to contribute to the correctional goal of rehabilitation. Previous studies provide theoretical justification as well as empirical evidence of religion helping prisoners achieve rehabilitation, thereby reducing their emotional and behavioral problems.

Bibliography

- Bahr, Stephen J. and John P. Hoffmann. 2010. “Parenting Style, Religiosity, Peers, and Adolescent Heavy Drinking.” Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 71 (4) (JUL): 539-543.

- Bahr, Stephen J. and John P. Hoffmann. 2008. “Religiosity, Peers, and Adolescent Drug Use.” Journal of Drug Issues 38 (3) (July 01): 743-769. doi:10.1177/002204260803800305. http://jod.sagepub.com/content/38/3/743.abstract.

- Batson, C. Daniel, Randy B. Floyd, Julie M. Meyer, and Alana L. Winner. 1999. “”And Who is My Neighbor?”: Intrinsic Religion as a Source of Universal Compassion.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38 (4): 445-457. doi:10.2307/1387605.

- Baumeister, Roy F. 1994. “The Crystallization of Discontent in the Process of Major Life Change.” In Can Personality Change?, edited by Todd F. Heatherton and Joel Lee Weinberger, 281-297. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Benjamins, Maureen Reindl and Carolyn Brown. 2004. “Religion and Preventative Health Care Utilization among the Elderly.” Social Science & Medicine 58 (1): 109-118.

- Boateng, A. C. O., K. C. Britt, C. Xiao, H. Oh, and F. Epps. 2021. “Decline in Religiosity: A Public Health Crisis.” Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing 7 (11): 1000313. doi:10.4172/2471-9846.1000313.

- Carney, Scott. 2017. What Doesn’t Kill Us: How Freezing Water, Extreme Altitude, and Environmental Conditioning Will Renew our Lost Evolutionary Strength. New York, NY: Rodale.

- Case, Anne and Angus Deaton. 2015. “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (49): 15078-15083.

- Clifton, Jon. 2022. Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and how Leaders Missed It. Washington, D.C.: Gallup Press.

- Cnaan, Ram and Stephanie C. Boddie. 2002. The Invisible Caring Hand: American Congregations and the Provision of Welfare. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Costin, Vlad and Vivian L. Vignoles. 2020. “Meaning is about Mattering: Evaluating

- Coherence, Purpose, and Existential Mattering as Precursors of Meaning in Life Judgments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 118 (4): 864-884. doi:10.1037/pspp0000225.

- Delle Fave, Antonella. 2020. “Eudaimonic and Hedonic Happiness.” In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-being Research, edited by Filomena Maggino, 1-7. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_3778-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_3778-2.

- Edgell, Penny. 2013. Religion and Family in a Changing Society. Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ellison, Christopher G. and Andrea K. Henderson. 2011. “Religion and Mental Health: Through the Lens of the Stress Process.” In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health, 11-44: Brill.

- Emmons, Robert A. 1999. The Psychology of Ultimate Concerns: Motivation and Spirituality in Personality. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Emmons, Robert A. and Raymond F. Paloutzian. 2003. “The Psychology of Religion.” Annual Review of Psychology 54: 377-402. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145024.

- Emmons, Robert A. and Michael E. McCullough, eds. 2004. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Evans, C. Stephen. 2022. Living Accountably: Accountability as a Virtue Oxford University Press.

- Forsberg, Lisa and Thomas Douglas. 2020. “What is Criminal Rehabilitation?” Criminal Law and Philosophy. doi:10.1007/s11572-020-09547-4.

- Frankl, Viktor E. 1984. Man’s Search for Meaning. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Giordano, Peggy C., Stephen A. Cernkovich, and Jennifer L. Rudolph. 2002. “Gender, Crime, and Desistance: Toward a Theory of Cognitive Transformation.” American Journal of Sociology 107 (4): 990-1064. - Giordano, Peggy C., Ryan D. Schroeder, and Stephen A. Cernkovich. 2007. “Emotions and Crime Over the Life Course: A Neo-Meadian Perspective on Criminal Continuity and Change.” American Journal of Sociology 112 (6): 1603-1661. doi:10.1086/512710.

- Hallett, Michael, Joshua Hays, Byron R. Johnson, Sung Joon Jang, and Grant Duwe. 2017. The Angola Prison Seminary: Effects of Faith-Based Ministry on Identity Transformation, Desistance, and Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Howard, Jeffrey W. 2017. “Punishment as Moral Fortification.” Law and Philosophy 36 (1): 45-75.

- Hummer, Robert A., Richard G. Rogers, Charles B. Nam, and Christopher G. Ellison. 1999. “Religious Involvement and US Adult Mortality.” Demography 36 (2): 273-285.

Jang, Sung Joon. 2016. “Existential Spirituality, Religiosity, and Symptoms of Anxiety-Related Disorders: A Study of Belief in Ultimate Truth and Meaning in Life.” Journal of Psychology and Theology 44 (3): 213-229. doi:10.1177/009164711604400304. - Jang, Sung Joon and Byron R. Johnson. 2017. “Religion, Spirituality, and Desistance from Crime: Toward a Theory of Existential Identity Transformation.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Life-Course Criminology, edited by Arjan Blokland and Victor van der Geest, 74-86. New York, N.Y.: Routledge.

- Jang, Sung Joon, Byron R. Johnson, and Matthew Lee Anderson. 2022. “Religion and Rehabilitation in Colombian Prisons: New Insights for Desistance.” Advancing Corrections Journal 14 (Article 2): 29-43.

- Jang, Sung Joon, Byron R. Johnson, Matthew Lee Anderson, and Karen Booyens. 2021. “The Effect of Religion on Emotional Well-being among Offenders in Correctional Centers of South Africa: Explanations and Gender Differences.” Justice Quarterly 38 (6): 1154-1181. doi:10.1080/07418825.2019.1689286.

- Jang, Sung Joon, Byron R. Johnson, Matthew Lee Anderson, and Karen Booyens. 2022. “Religion and Rehabilitation in Colombian and South African Prisons: A Human Flourishing Approach.” International Criminal Justice Review. doi:10.1177/10575677221123249.

- Jang, Sung Joon, Byron R. Johnson, Joshua Hays, Michael Hallett, and Grant Duwe. 2018. “Religion and Misconduct in “Angola” Prison: Conversion, Congregational Participation, Religiosity, and Self-Identities.” Justice Quarterly 35 (3): 412-442. doi:10.1080/07418825.2017.1309057.

- Johnson, Byron R. 2004. “Religious Programs and Recidivism among Former Inmates in Prison Fellowship Programs: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study.” Justice Quarterly 21 (2): 329-354.

- Johnson, Byron R. 2011. More God, Less Crime: Why Faith Matters and how it could Matter More. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press.

- Johnson, Byron R. and David B. Larson. 2003. The InnerChange Freedom Initiative: A Preliminary Evaluation of a Faith-Based Prison Program. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society.

- Johnson, Byron R. and William Wubbenhorst. 2017. Assessing the Faith-Based Response to Homelessness in America: Findings from Eleven Cities. Waco, TX: Institute for Studies of Religion.

- Johnson, Byron R., Michael Hallett, and Sung Joon Jang. 2022. The Restorative Prison: Essays on Inmate Peer Ministry and Prosocial Corrections Routledge.

- Johnson, Byron R., Ralph Brett Tompkins, and Derek Webb. 2008. Objective Hope: Assessing the Effectiveness of Faith-Based Organizations: A Review of the Literature. Waco, TX: Institute for Studies of Religion.

- Kelly, P. Elizabeth, Joshua R. Polanin, Sung Joon Jang, and Byron R. Johnson. 2015. “Religion, Delinquency, and Drug use: A Meta-Analysis.” Criminal Justice Review 40 (4) (December 01): 505-523. http://cjr.sagepub.com/content/40/4/505.abstract.

Koenig, Harold G. 2015. “Religion, Spirituality, and Health: A Review and Update.” Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 29 (3): 19-26. - Koenig, Harold G., Dana G. King, and Verna Benner Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health. Second ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Krause, Neal. 2018. “Assessing the Relationships among Religion, Humility, Forgiveness, and Self-Rated Health.” Research in Human Development 15 (1): 33-49. doi:10.1080/15427609.2017.1411720.

- Lam, Pui–Yan. 2002. “As the Flocks Gather: How Religion Affects Voluntary Association Participation.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41 (3): 405-422.

- Lee, Matthew T., Maria E. Pagano, Byron R. Johnson, Stephen G. Post, George S. Leibowitz, and Matthew Dudash. 2017. “From Defiance to Reliance: Spiritual Virtue as a Pathway Towards Desistence, Humility, and Recovery among Juvenile Offenders.” Spirituality in Clinical Practice 4 (3): 161.

- Lim, Chaeyoon and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. “Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction.” American Sociological Review 75 (6): 914-933. doi:10.1177/0003122410386686.

- Mahoney, Annette, Kenneth I. Pargament, Aaron Murray-Swank, and Nichole Murray-Swank. 2003. “Religion and the Sanctification of Family Relationships.” Review of Religious Research: 220-236.

- Makridis, Christos A., Byron R. Johnson, and Harold G. Koenig. 2021. “Does Religious Affiliation Protect People’s Well‐Being? Evidence from the Great Recession After Correcting for Selection Effects.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 60 (2): 252-273.

- Makridis, Christos Andreas. 2020. “Human Flourishing and Religious Liberty: Evidence from Over 150 Countries.” Plos One 15 (10): e0239983. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239983.

- Maruna, Shadd. 2001. Making Good: How Ex-Convicts Reform and Rebuild their Lives. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- McCullough, Michael E., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Carl E. Thoresen, eds. 2000. Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- McClure, Jennifer M. 2013. “Sources of Social Support: Examining Congregational Involvement, Private Devotional Activities, and Congregational Context.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52 (4): 698-712.

- McCullough, Michael E. 2008. Beyond Revenge: The Evolution of the Forgiveness Instinct John Wiley & Sons.

- McCullough, Michael E., Giacomo Bono, and Lindsey M. Root. 2005. “Religion and Forgiveness.” Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality: 394-411.

- McNeill, Fergus. 2012. “Four Forms of ‘offender’ Rehabilitation: Towards an Interdisciplinary Perspective.” Legal and Criminological Psychology 17 (1): 18-36.

- McNeill, Fergus. 2014. “Punishment as Rehabilitation.” In Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice, edited by Gerben Bruinsma and David Weisburd, 4195-4206. New York, NY: Springer New York.

- McNeill, Fergus, Stephen Farrall, Claire Lightowler, and Shadd Maruna. 2012. “How and Why People Stop Offending: Discovering Desistance.” Insights Evidence Summary to Support Social Services in Scotland.

- Park, Crystal L. 2005. “Religion as a Meaning‐making Framework in Coping with Life Stress.” Journal of Social Issues 61 (4): 707-729.

- Paternoster, Ray and Greg Pogarsky. 2009. “Rational Choice, Agency and Thoughtfully Reflective Decision Making: The Short and Long-Term Consequences of Making Good Choices.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 25 (2): 103-127. doi:10.1007/s10940-009-9065-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10940-009-9065-y.

- Putnam, Robert D., Lewis Feldstein, and Donald J. Cohen. 2004. Better Together: Restoring the American Community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Reker, Gary T., Edward J. Peacock, and Paul TP Wong. 1987. “Meaning and Purpose in Life and Well-being: A Life-Span Perspective.” Journal of Gerontology 42 (1): 44-49. doi:10.1093/geronj/42.1.44.

- Rosmarin, David H. and Harold G. Koenig, eds. 2020. Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health. Second ed.: Academic Press.

- Ryan, Richard M. and Edward L. Deci. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55 (1): 68-78. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68.

- Rye, Mark S., Kenneth I. Pargament, M. Amir Ali, Guy L. Beck, Elliot N. Dorff, Charles Hallisey, Vasudha Narayanan, and James G. Williams. 2000. “Religious Perspectives on Forgiveness.” In Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Michael E. McCullough, Kenneth I. Pargament and Carl E. Thoresen, 17-40. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Schnitker, Sarah A., Pamela E. King, and Benjamin Houltberg. 2019. “Religion, Spirituality, and Thriving: Transcendent Narrative, Virtue, and Telos.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 29 (2): 276-290. doi:10.1111/jora.12443.

- Smith, Christian. 2003. Moral, Believing Animals: Human Personhood and Culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Steger, Michael F. and Patricia Frazier. 2005. “Meaning in Life: One Link in the Chain from Religiousness to Well-being.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52 (4): 574-582. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.574.

- Steger, Michael F., Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2006. “The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 53 (1): 80-93. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80.

VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2020. “Activities for Flourishing: An Evidence-Based Guide.” Journal of Positive School Psychology 4 (1): 79-91. - VanderWeele, Tyler J. 2017. “On the Promotion of Human Flourishing.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (31): 8148-8156. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702996114.

VanderWeele, Tyler J. “How Religious Community is Linked to Human Flourishing: An Analysis Explores how Service Attendance Relates to Health and Well-Being.” Psychology Today., last modified February 25, accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/human-flourishing/202102/how-religious-community-is-linked-human-flourishing. - VanderWeele, Tyler J. and Case, Brendan. “Empty Pews are an American Public Health Crisis: Americans are Rapidly Giving Up on Church. our Minds and Bodies Will Pay the Price.” Christianity Today., last modified October 19, accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2021/november/church-empty-pews-are-american-public-health-crisis.html.

- VanderWeele, Tyler J., Jeffrey Yu, Yvette C. Cozier, Lauren Wise, M. Austin Argentieri, Lynn Rosenberg, Julie R. Palmer, and Alexandra E. Shields. 2017. “Attendance at Religious Services, Prayer, Religious Coping, and Religious/Spiritual Identity as Predictors of all-Cause Mortality in the Black Women’s Health Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology 185 (7): 515-522.

- Ward, Tony. 2002. “Good Lives and the Rehabilitation of Offenders: Promises and Problems.” Aggression and Violent Behavior 7 (5): 513-528.

- Ward, Tony. 2010. “The Good Lives Model of Offender Rehabilitation: Basic Assumptions, Etiological Commitments, and Practice Implications.” In Offender Supervision: New Directions in Theory, Research and Practice, 41-64: Routledge New York, NY.

- Ward, Tony and Mark Brown. 2004. “The Good Lives Model and Conceptual Issues in Offender Rehabilitation.” Psychology, Crime & Law 10 (3): 243-257. doi:10.1080/10683160410001662744.

- Ward, Tony and Shadd Maruna. 2007. Rehabilitation. New York: Routledge.

- Wilson, John and Marc Musick. 1997. “Who Cares? Toward an Integrated Theory of Volunteer Work.” American Sociological Review: 694-713.

- Witter, Robert A., William A. Stock, Morris A. Okun, and Marilyn J. Haring. 1985. “Religion and Subjective Well-being in Adulthood: A Quantitative Synthesis.” Review of Religious Research: 332-342.

To read and download the full eBook ‘Human flourishing and offender rehabilitation’ click here