The FQHCs handle 114.2 million patient visits per year. In 2021, one of 4 of these visits was virtual and involved the use of telemedicine, here we explore the value of telemedicine for diabetes patients in rural areas of America

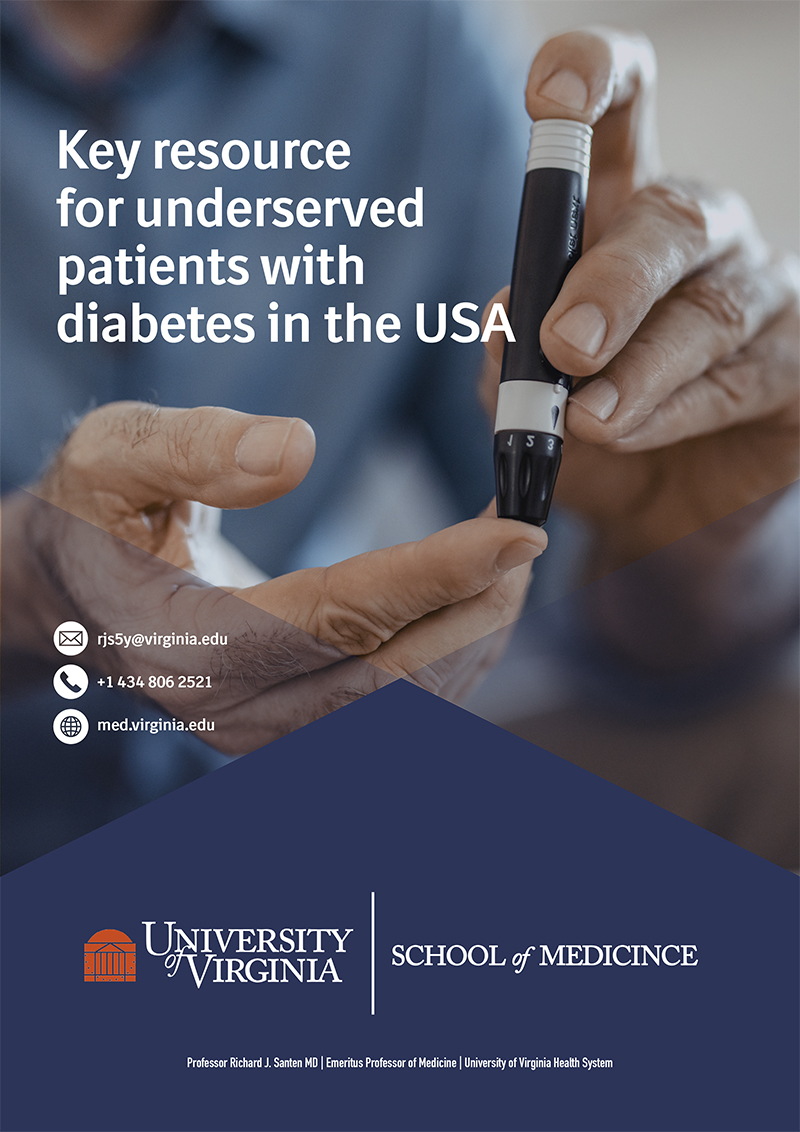

Patients with diabetes mellitus living in rural, underserved areas have difficulty receiving appropriate medical care because of problems with transportation, medical insurance, geographical issues, multiple disease comorbidities, educational factors, lack of endocrinologists and a myriad of other issues. Telemedicine provides an efficient way to ameliorate most of these obstacles. A large percentage of the geographical area in the United States is rural, particularly in the Midwest and western part of the country (Figure 1.) This treatise will consider what programs are in place to help care for patients in these rural areas.

Government Program

In the United States, the federal government has funded clinics specifically directed toward patients living in rural areas. Called the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), these 13,555 clinics receive $5.7 billion of government support yearly.

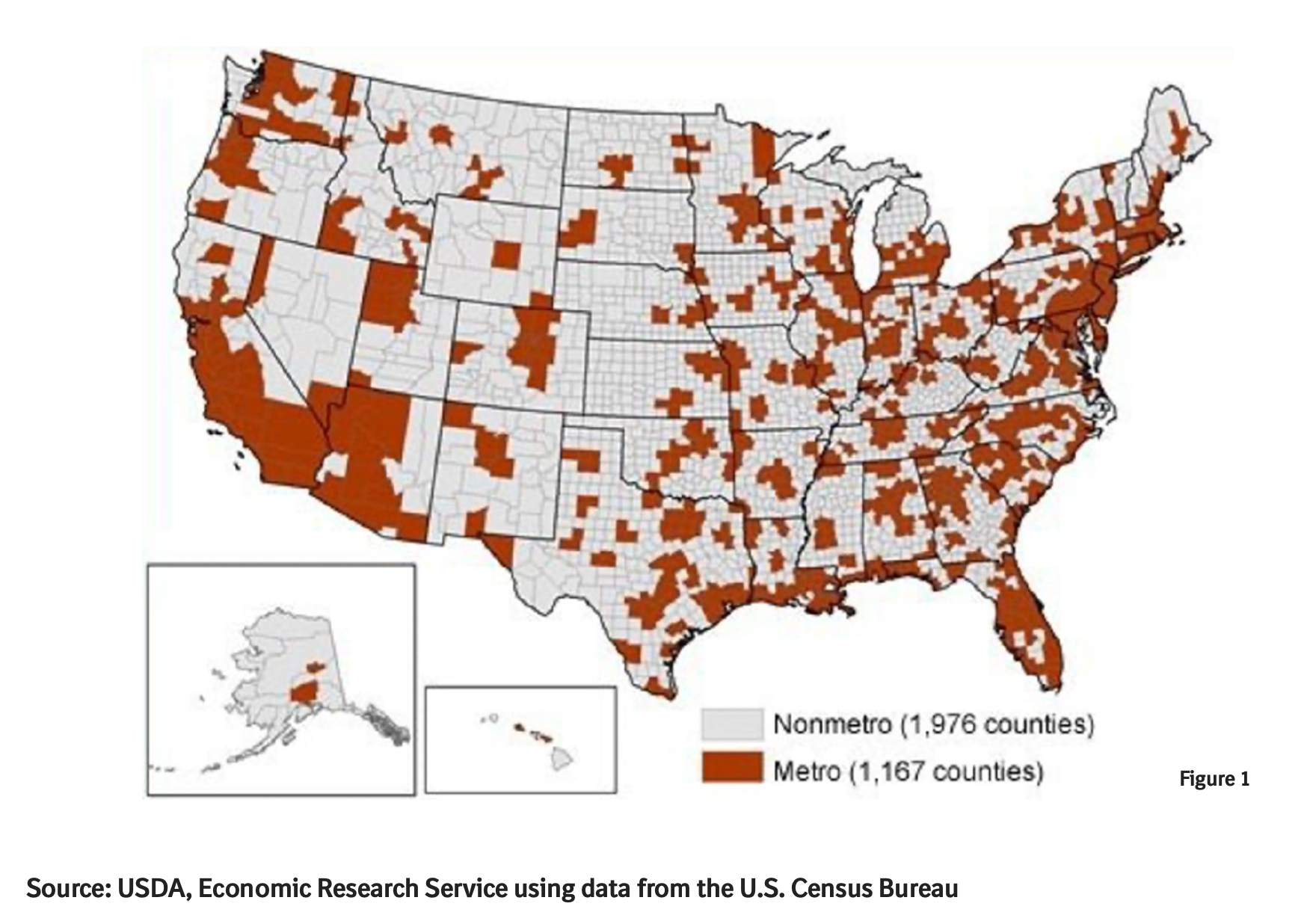

The FQHC system provides funding for 255,000 personnel (full-time equivalents —FTEs) and supports substantial infrastructure in order to enhance the quality of care delivered. Of the individuals hired by the FQHCs, 18% are nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other medical personnel; 17% are physicians; 23% are nurses; and 42% are other medical personnel. The practice types include family physicians who represent 46%; general practitioners, 4%; pediatricians, 22%; obstetric/gynecologists, 9%; and internists, 15%. Specialists represent a minority (20%) of the physicians hired by these clinics (figure 2 above) and are usually professionals contracted from outside of the FQHC system.

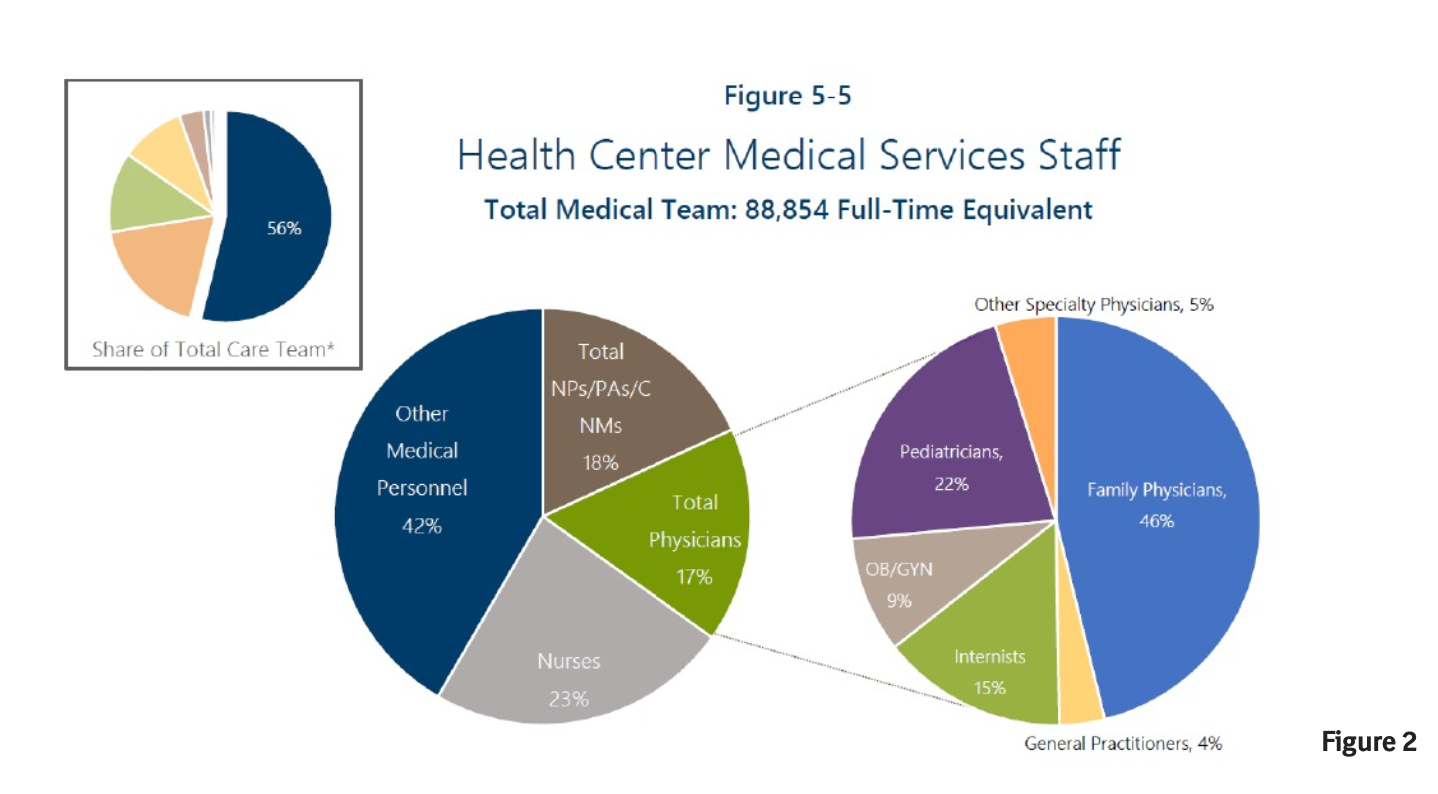

Each state has multiple Federally Qualified Health Centers (figure 3). For example, California has 268, New York 63, Oregon 30, and Texas 22. These data suggest that most individuals living in rural areas will have a FQHC geographically available to them.

Statistics regarding the FQHCs

The statistical data regarding these centers provides keen insight into the volume and types of patients seen. The FQHCs handle 114.2 million patient visits per year. In 2021, one of 4 of these visits was virtual and involved the use of telemedicine. The majority of visits were for primary care, but some were for dental and mental health problems. The federal government covers part of the cost of medical care for patients attending these clinics.

Specifically, on a per-patient-visit basis, $45 comes from federal grant dollars and $57 from insurance coverage. In 2021, the state health insurance program called Medicaid covered 39.5% of the overall patient health costs, whereas the federal government program called Medicare covered another 10%. Unfortunately, 21.8% of patients had no insurance whatsoever. For these patients, the federal government has a program called MAT (Medication-Assisted Treatment), which covers uninsured patients, and 181,896 patients received this assistance in 2020.

The demographic makeup of the patients attending these clinics includes 21% African- American, 37% Hispanic, 4% Asian, and 1.5% American Indian. The remainder designates themselves as non-Hispanic white or Caucasian. Of these, 8.14 million designated themselves as male, 11.7 million as female, 7.79 million as other, and 7.16 million as unknown. With respect to ages, 10% of patients were older than age 65; 62% were aged 18-64; and 27% were from 0 to 17 years old. It is of note that 18% of patients attending the FQHCs were homeless and another 18% live in public housing.

When assessing the impact of the FQHCs, 1 and 9 children or adolescents living in the United States received care in this program; 1 out of 7 ethnic minorities, 1 in 5 of uninsured patients, and 1 and 3 people living in poverty. Of the patients attending these clinics, 67% were below the federal property level, and 15% were between the 101 and 150 percentile of the federal poverty level.

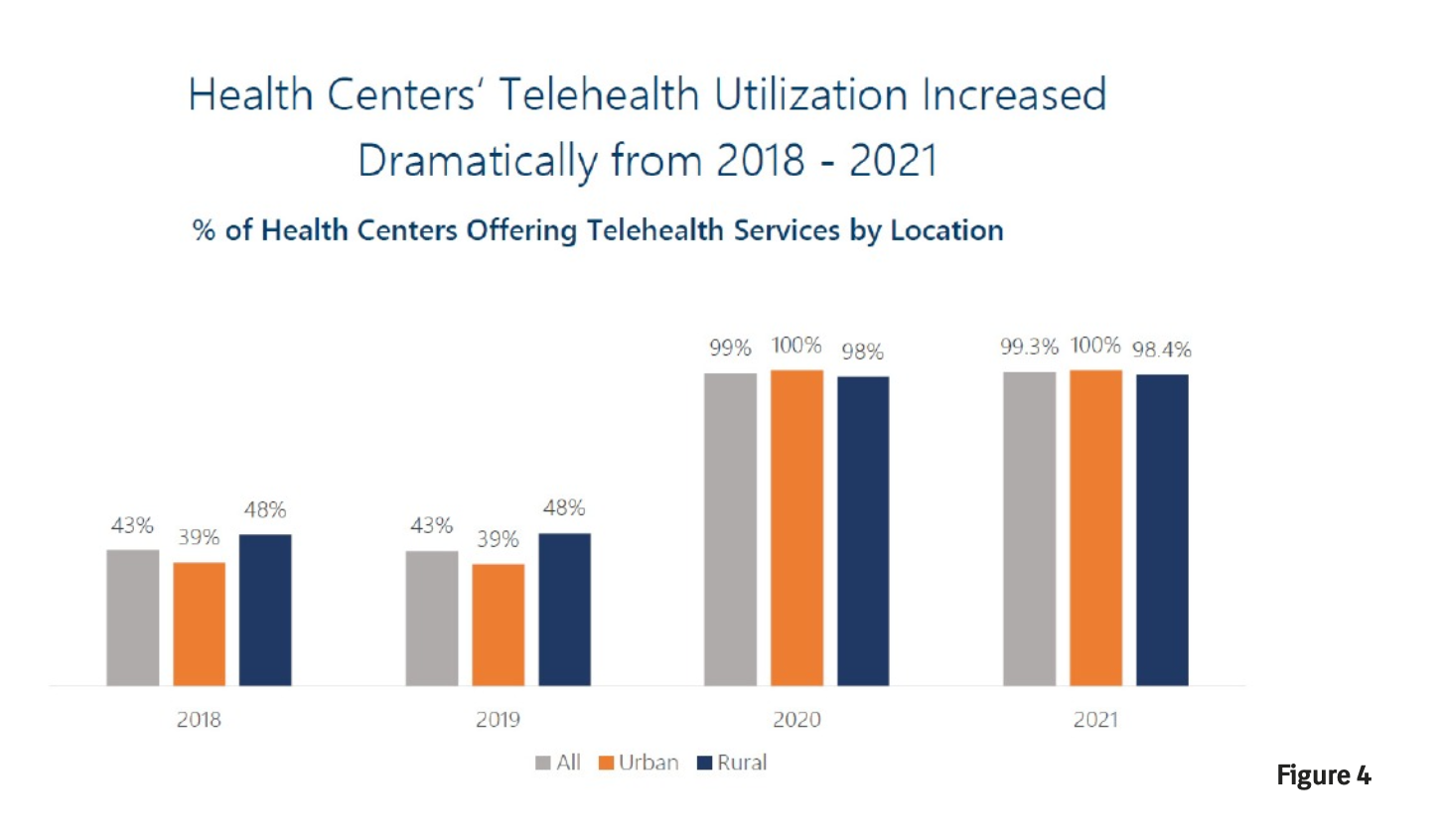

Because of the COVID epidemic, the number of patients seen by telemedicine has markedly increased dramatically over a three-year interval (figure 4). In 2021, 98%% of the FQHCs offered telehealth services, whereas only 48 % offered this in 2018.

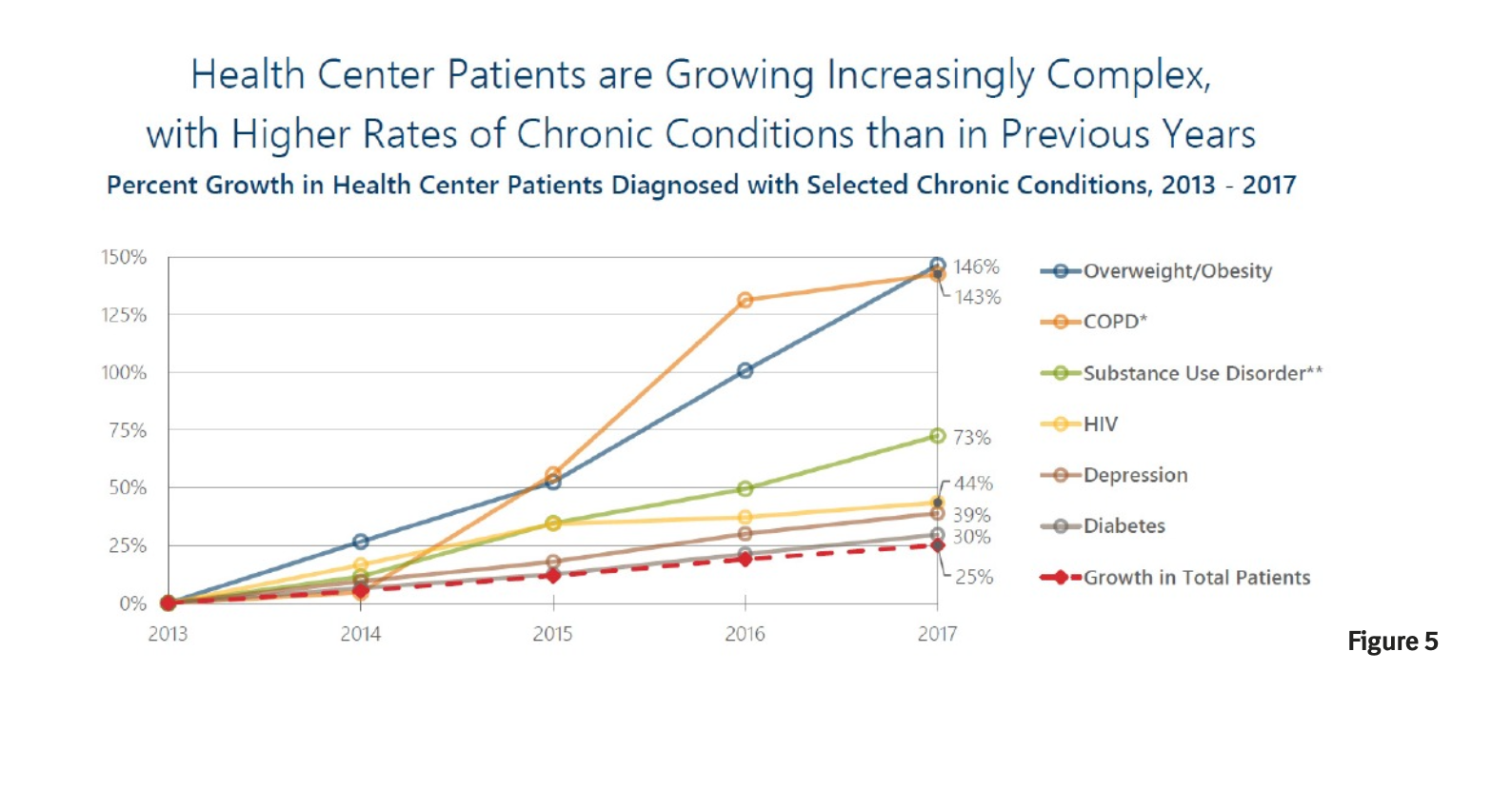

Obesity and diabetes mellitus are common conditions currently being treated in the FQHCs and these numbers are gradually increasing (Figure 5). Of all the patients seen in 2017, 21% were diagnosed with diabetes. The greatest increase in various conditions from 2013-2017 was diabetes. This closely paralleled the increase in overweight and obesity, which increased by 146%.

Shortage of Providers

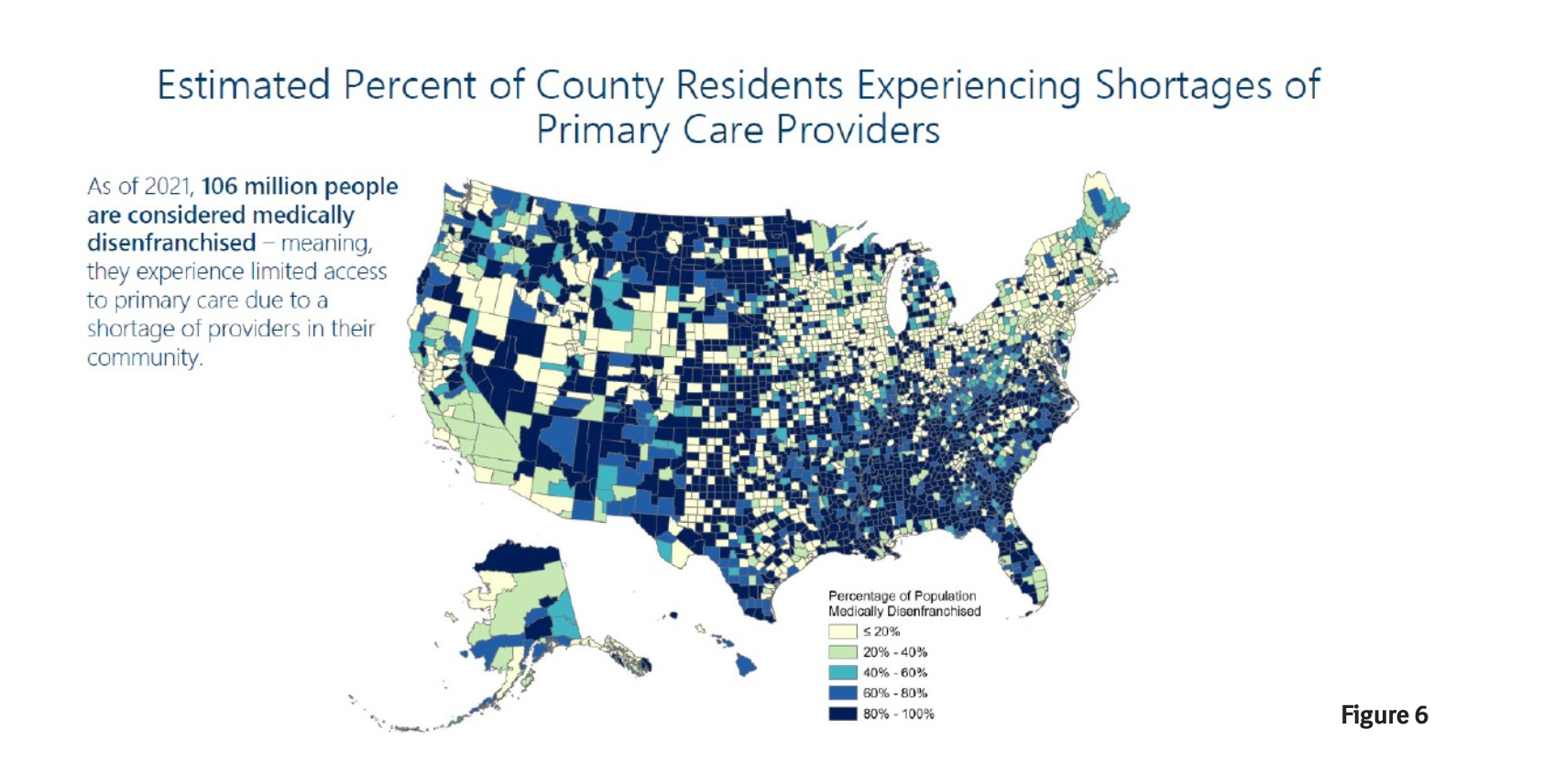

Over the last three decades, there has been a major emphasis that shortages in primary care providers exist across the country. Many programs have been developed to try to ameliorate this situation but without much success. As of 2021, 106 million people in the United States were considered medically disenfranchised–meaning they experience limited access to primary care due to a shortage of providers in their community. Figure 6 illustrates the estimated percentage of County residents experiencing shortages of primary care providers in the United States.

Partial Solution

What can be done about the shortage of specialists available to patients in rural areas in the United States? During the COVID epidemic, the utilization of telemedicine increased dramatically, which demonstrated the feasibility of this means of caring for patients. However, the number of specialists available to take care of patients with diabetes is limited. There are approximately 37.3 million individuals with diabetes in the United States, and the number increases yearly.

Despite this increasing number, many patients do not have ready access to endocrinologists. In 2022, the number of endocrinologists in the United States was estimated to be 8240, a ratio of individuals with diabetes or other endocrine disorders to endocrinologists at 4375 to 1. For that reason, the great majority of diabetes care takes place in the primary care setting and without the input of endocrinologists.

How can the efficiency of this process be increased with the existing number of endocrinologist to take care of patients with diabetes? The clinical benefit of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has been well demonstrated in type 2 patients with diabetes, specifically with a demonstrable reduction in hemoglobin A1c. This methodology is particularly suited to telemedicine as endocrinologists can look at precise glucose data on their computers and make recommendations about treatment. Even with this increase in efficiency, the number of endocrinologists is insufficient to manage all of the patients with diabetes, needing expert input into their management.

“Rebooting” Retired Endocrinologists

The hypothesis has been raised that recruiting retired endocrinologist back into the workforce

( “rebooting”) to see patients with diabetes would provide a partial solution to this problem. When collaborating with FQHCs, the retired endocrinologist can benefit from all of the personnel and infrastructure available in this federally funded program. Each FQHC has a large team that collaborates with the endocrinologist to facilitate efficient patient management ( Figure 7). I have been working with these clinics over the last 6 years and have found that this is the practice of endocrinology without the hassles. I can take a detailed history and review physical exams via telemedicine and review all of the laboratory data available sent to me electronically.

After an initial assessment, I can advise changes in lifestyle, diet, medication, and lipid management. The nurse educator at the clinics serves as a liaison between myself and the providers who are individually managing each patient. By weekly telephone calls utilizing glucose monitor or CGM data, I can make recommendations each week little while patients to become under good control relatively rapidly. We have published our data indicating a marked reduction in hemoglobin A1c in these patients and a relative lack of recidivism after the patient has finished with a 6 month self-management education program.

Designated goal

A desired goal at the present time is to recruit retired endocrinologists to follow the template that I have established for telemedicine andtreatment of patients with diabetes cared for in the FQHCs. To find out exactly what this entails, we have constructed a website which outlines the program, provides a roadmap for getting started, shows a video of an example of the interviews with a patient and spouse and nurse practitioner, and blogs which go into extensive detail about the process. My own experience with telemedicine is that this has been rewarding, does not involve large time constraints, allows me to get to know patients well, and is well accepted by the patients. The bibliography contains key references and our publications describing this experience.