There is a 2-minute corrective exercise which research proves provides relief from low back pain to 90% of those who do it, explains Dr. Hélène Bertrand, who discusses the impact of SI joints and possible pain treatments

Over 80% of adults at some time in their lives are afflicted by lower back pain (LBP)1. Despite the availability and wide use of diagnostics based on imaging, (ultrasound, CT scans, MRIs, x-rays), and laboratory tests, between 85% and 95% of the time this pain is diagnosed to be “nonspecific”, which means that “we don’t know the cause”. 2,3

As a result, the treatment of most LBP does not address a properly diagnosed cause. Because of the lack of proper diagnostics, many different treatments are used, mostly without lasting success, so that LBP is now the commonest cause of disability in the world.4,5

This e-book describes a reliable and easy way to find a cause for most LBP and suggests a specific treatment for it that is non-invasive, quick, safe and simple to administer. People with this condition can treat themselves in 2 minutes with a 90% chance of finding relief.

The Basic Problem

The diagnosis of nonspecific LBP is challenging. Medical imaging tests are used to assess LBP, but the diagnoses of lumbar spine instability, spinal stenosis, and degenerative disc disease most often do not lead to treatments that result in lasting relief, much less a cure.6,7,8,9,10

My clinical experience has led me to discover that the dominant cause for LBP is sacroiliac (SI) joint displacement, which originates in the buttocks, just below the spine, where the anatomy makes the condition impossible to see using routine medical imaging or to feel through normal physical examination.11,12,13,14,15

I have developed a way to examine the SI joints to find out in what direction the pelvic bones are displaced. Depending on how they are displaced a simple corrective exercise to realign the joints can be done.

About the SI joints

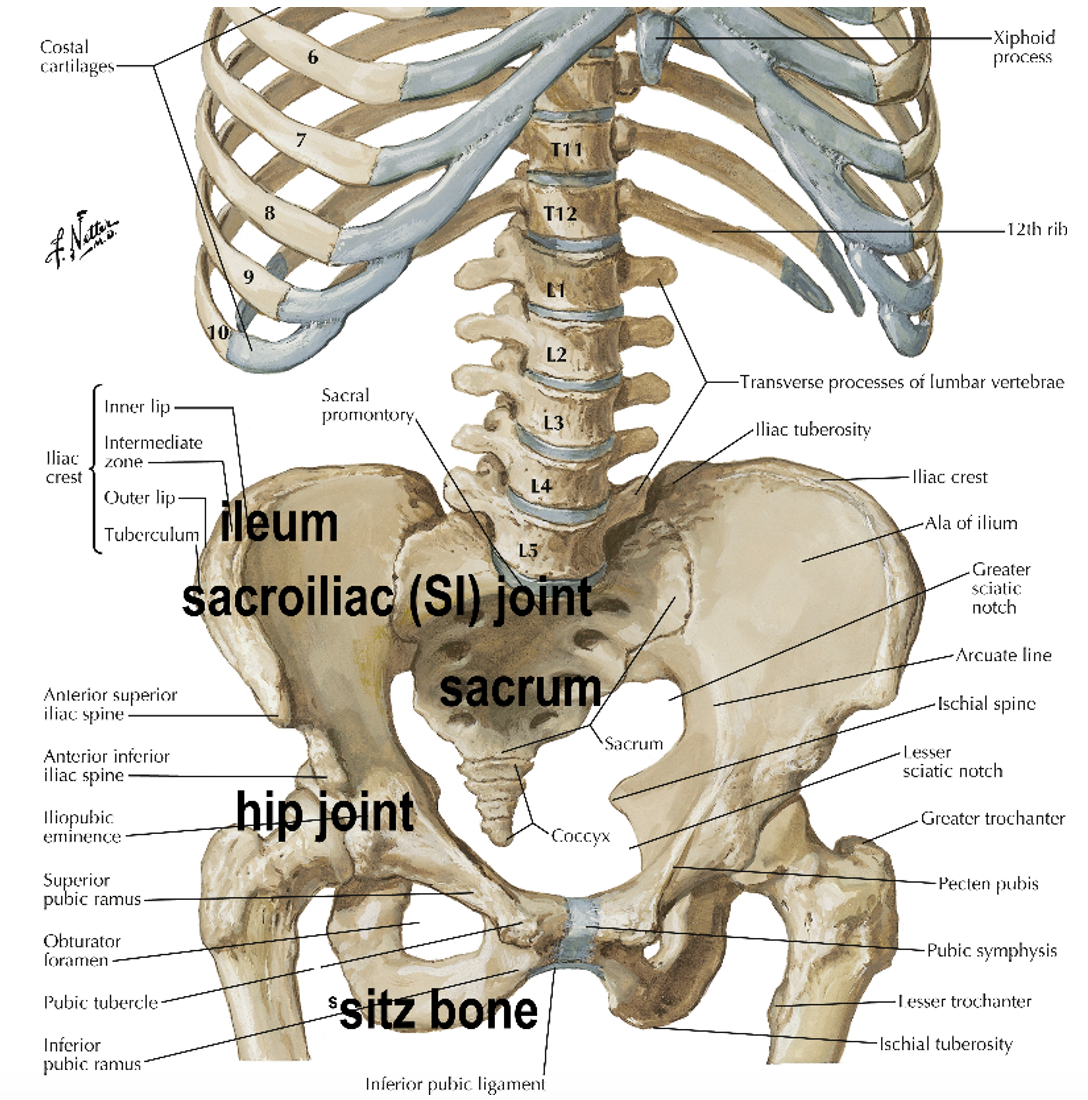

The method I use for diagnosing the cause of LBP can best be understood by considering the shape and location of the SI joints in the body, which are shown in the following illustrations from Frank Netter: Atlas of human anatomy.16

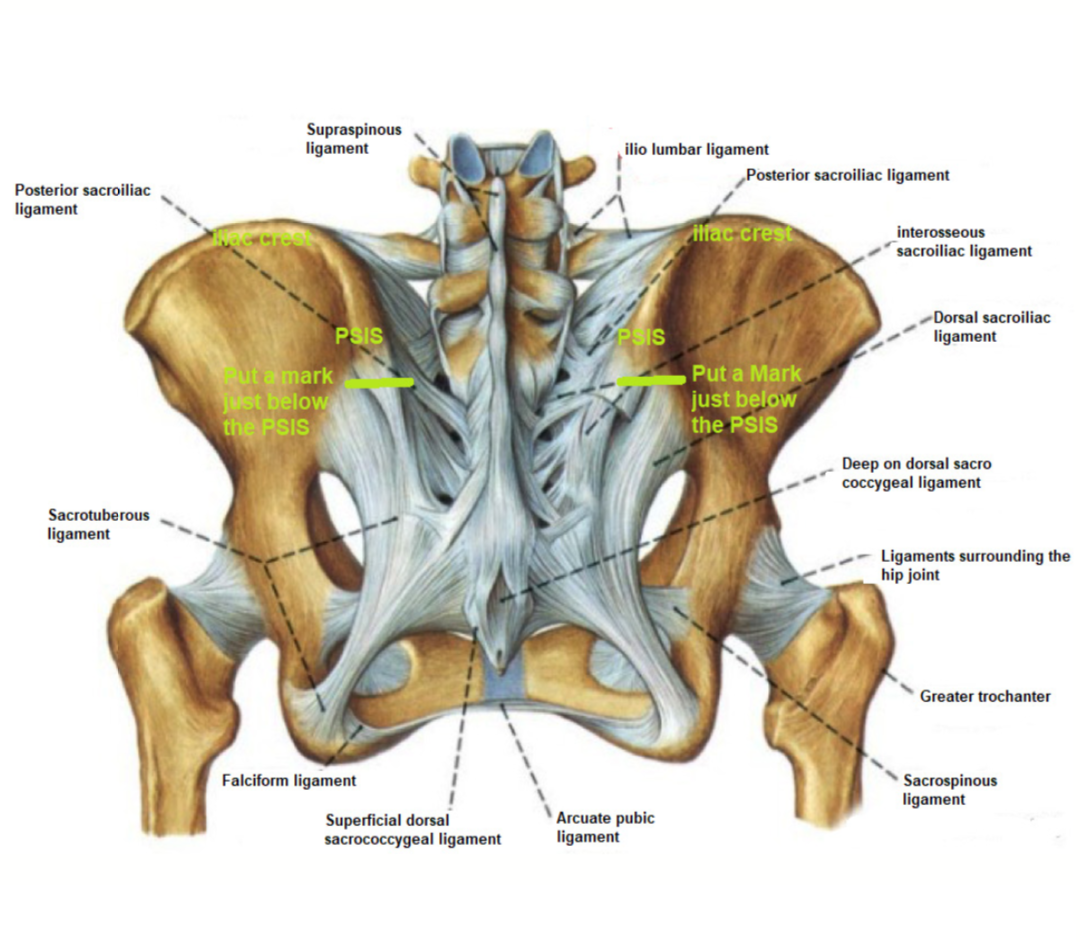

Figure 1 shows the location of the pelvic bones (ileum), which are joined on either side to the sacrum, forming the sacroiliac (SI) joints. The weight of the upper body rests on the pelvic bones and tends to push them away from the sacrum. The hip joint, which is inside the pelvic bone, moves the pelvic bones every time the legs are used. These 2 facts mean that the SI joints are under more stress than any other joint in the body and because of this, they need to be held in place by the body’s largest network of ligaments as you can see on

Figure 2. The SI joints have a very important function. They protect the spine by absorbing the shock to the hip joint transmitted by the leg every time the foot hits the ground. To carry out this shock absorber function, unlike the other joints in the body which are smooth, SI joints are full of irregularities. This makes it impossible to judge their alignment and position with medical imaging (X rays, CT scans, MRIs). I believe that the displacement of SI joints and accompanying strains on the ligaments holding them in place is the primary cause for the non-specific LBP that has puzzles so many clinicians.

Figure 1: image of a skeleton showing the lumbar spine, the pelvis, and their connections.

Causes of SI displacement

SI displacement is usually caused by common events such as falls landing on the buttocks, rear-end car accidents where the foot on the brake jolts the hip joint, landing hard from a jump, long or downhill runs, going down long flights of stairs, wrong sleeping position etc.… When the weight of the upper body pushes the pelvic bones away from the sacrum the SI joint becomes unstable: prolonged sitting, lifting weights or being overweight can displace them.

LBP originating with the SI joints can also be the result of uneven leg length (you land harder on the shorter leg, jolting its SI joint) or lower spine fusion putting strain on the SI joint. People with weaker ligaments also have trouble keeping their SI joints together. Collagen, that ligaments are made of, is weakened by pregnancy hormones needed to allow passage of the baby’s head through the pelvis.

People who inherit overly elastic collagen, which causes them to be double jointed, often sprain their SI joints. The commonest cause of collagen loss is aging, which often leads to sagging skin and to weaker ligaments, resulting in arthritis and displaced SI joints.17

These conditions lead to LBP because when the SI joints are displaced, the nerves in the overstretched ligaments around the SI joints transmit pain signals to the brain, which is nature’s way to get people to stop engaging in activities that stress the joints.

Determining the Direction and Size of SI joint displacements

Strain on the SI joints is caused by displacement of the pelvic bones, and medical imaging cannot indicate the direction and size of this displacement. It must instead be found by physical examination, which involves the following procedure.

Move your finger along the iliac crest to find the Posterior Superior Iliac Spine (PSIS), which is a small, hard bump on either side of the anal cleft (the crack). How to find the PSISs. Once found on both sides of the back, the locations of the PSIS should be marked with a pen so their levels can be compared. Pressing down on the underside of the PSIS will elicit pain if the pelvic bone is displaced.

Next, compare the relative heights of the PSISs. If they are the same, the patient’s LBP is not caused by SI joint displacement and cannot be relieved by the procedure described below.

However, in my experience, most patients with LBP have PSISs at different heights. This difference is important for reducing the displacement discussed below. On the side where the PSIS is higher the pelvic bone is displaced towards the front. On the side where it is lower the pelvic bone is displaced backwards.

The size of the difference in the height of the two PSISs indicates the extent to which the SI joints are displaced and can be seen easily, but for more precision it can be measured with the help of a spirit level.

Correcting the SI Joint Displacement

The following description of the corrective exercises can be understood more easily by looking at Figure 3, which shows a patient engaged in repositioning a pelvic bone that is tilted forward on the right and backwards on the left.

To reposition a higher PSIS, which means the pelvic bone is tilted forward, it needs to be pushed backwards using the thigh. The leg on the affected side is bent with the foot on the floor. The patient leans forward and places the hands on the floor on either side of the foot. This position causes a strong backward pressure of the left thigh on the pelvic bone, which may be uncomfortable but essential to push the bone back into its normal position.

To reposition a lower PSIS, meaning the pelvic bone is tilted backwards, the bone will have to be pulled forward. The muscles which attach to the front of the pelvic bone and to the leg will pull the pelvic bone forward as the thigh is stretched, pulling on these muscles. With the left knee on the ground and the right foot on the floor, they lean forward and slide their knee backwards until a strong pull is felt in the groin. The pull can be uncomfortable but is essential to get the SI joint to move to its normal position.

These exercises must last two minutes during which patients may experience discomfort, making the two minutes seem very long. Note the patient looking at his cell phone timer on the floor in front him. However, holding the position for 2 minutes is essential for the success of the procedure.

One important feature of the corrective exercise just described is that, once they understand the procedure, people with recurrent LBP can treat themselves with occasional help from relatives or friends who can assess the relative height of their PSISs. There is no cost for this treatment.

After the treatment, the position of the PSISs must be re-assessed. If they are level and the pain is gone, the treatment has been successful.

In some cases, the PSISs are level but the LBP persists. This means that the SI displacement was not the only cause of LBP. The patient needs further medical assessment.

If after the treatment, pain persists and the PSISs are not level, the treatment needs to be repeated. Some people who are double-jointed (hyper mobile) can sometimes move their PSISs in the opposite direction with the exercise. In this case, the exercise should be done in the opposite direction but only for 1 minute and that should, from now on, be the time they use for doing the exercise.

Some patients experience repeated episodes of LBP. This indicates that their SI joints are unstable because the ligaments holding them are weak, torn, or excessively stretchy. Such patients benefit from wearing a pelvic support belt like the widely available Serola belt. The belt must be worn below the bones that can be felt in front of the iliac crest and below the PSISs, directly over the SI joints. Higher positions of the belt can lead to increased joint displacement and LBP.

Prolonged sitting causes the displacement of the Si joint and LBP because the weight of the upper body pushes the pelvic bones away from the sacrum. Sitting on a “doughnut” – shaped inflatable cushion keeps the sitz bones inside the hole in the center of the doughnut and prevents the pelvic bones from moving apart, away from the sacrum, thus avoiding LBP that otherwise would develop.

Patients with chronic SI and LBP problems can also use prolotherapy to rebuild the ligaments holding the SI joints.19 They can use surgery to have their sacrum and ileum bolted together, which closes the SI joint permanently.

These interventions require well trained professionals and are very costly. Surgery involves the risk of complications and increased strain on the lumbar spine because fusing the joint eliminates its shock absorbing function.

This LBP complete video describes the SI joints, how to find someone else’s PSISs, how to check their level, how to do the different corrective exercises, how to apply a pelvic support (Serola) belt and what happens to the people who do the 2-minute exercise.

Clinical experience and research

For 12 years I focused my family practice on treating people with chronic pain. Many were referred to me from other physicians who had been unable to deal with their pain.

My work was very rewarding. After the 2-minute procedure, some people would get up, test their back, and exclaim: “this is a miracle!” Over the years, they had tried so many treatments and this was the only one that provided them with such immediate relief.

I reviewed the charts of those I had treated for LBP between 2015 and 2017. In those 3 years, I saw 180 new patients suffering from this condition. I found that 14, 9%, had LBP caused by conditions other than displaced SI joints. I treated the remaining 164 patients with the 2-minute corrective exercise, 141, or 86% experienced immediate pain relief.

In 2019 and 2020, I did a study on 62 new patients with a displaced SI joint, which were randomized into three groups:21

- 21 received the corrective exercise.

- 21 used the pelvic support belt.

- 20 received their usual treatment: chiropractic manipulation, physiotherapy, massage, painkillers etc.

All participants completed questionnaires in which they indicated their level of LBP, between 0, no pain and 10, the worst imaginable pain.

At the first visit, group one, who received the SI corrective exercise, came in with an average pain score of 5.24 and, as soon as they had finished the exercise, the average pain score was down to 2. Group two, when they started wearing the Serola pelvic support belt, saw their pain go from an average of 4.48 when they arrived at the office to 2.33 after they put on the belt. Pain relief was still present when the corrective exercise and the pelvic support belt groups came back a month later while the people getting their usual treatment showed almost no difference in pain score. At that second visit, everybody got both the corrective exercise and the belt and 56 of the 62 participants (90%) experienced immediate LBP relief after the corrective exercise which was still present when they came back a month later.

At the 2-month visit, everybody had used the corrective exercise and the pelvic support belt for a month. They redid the exercise in the office. Following this, the average pain score in group 1 was 0.64, in group 2 it was 1.36 and in group 3, it was 0.61. All of them had found relief from their LBP with the corrective exercise and the belt. This leads me to believe that most patients suffering from LBP because of displaced SI joints can relieve their pain with the corrective exercise and wearing a pelvic support belt.

If you want to know more than what is in this presentation, here is a 45 minute Zoom Meeting on Low Back Pain you can check out.

Find research summary

Debilitating chronic LBP affects a very large proportion of people during their lifetime. The pain is disabling and costly to those who suffer. It affects their work, their emotions, their sleep, and their ability to function.

Unfortunately, current standards of care do not address the most common cause of this so-called “non-specific” LBP: the displacement of the pelvic bones stretching the ligaments of the SI joint, causing the nerves in these overstretched ligaments to send LBP signals to the brain.22

I have discovered a non-invasive method to assess in what direction, and how much, the pelvic bone on the painful side is displaced and have developed a simple, safe procedure to return the pelvic bone to its normal position. This relieves the strain on the SI joint and ends the back pain, indicating that “nonspecific” LBP is, in fact, usually caused by displaced pelvic bones.

I hope that health professionals will begin to use this technique for treating LBP and that public awareness of the technique can be increased, so that those with LBP can learn how to treat themselves.

The study presented here is small and the follow-up is short, only two months. It was going to be replicated in Kochi, Kerala, India. As I was leaving Kochi, having trained 6 physicians so they could carry out the research, they told me they had never seen so many people with LBP leave their office with a big smile on their face. Unfortunately, one month later in March 2020, Covid put an end to this project. I am planning a larger trial with a longer follow-up on a different population, to establish the global significance of this procedure. If you are interested in carrying out such a project, please reach out to me.

A future solution to treat lower back pain

A new way to assess the levels of the SI joints and a quick and effective treatment to correct their displacement. Could this be a solution for most LBP?

References

- Deyo RA, Tsui-Wu YJ. Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987; 12:264

- Https://IASP-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-global-burden-of-low-back-pain/

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians, American College of Physicians, American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478- 491.

- Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, Blyth FM, Smith E, Buchbinder R, Hoy D. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Trans Med 2020; 8(6): 299-313.

- Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, et al. Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ 1998; 316:1356.

- Traeger AC, Gilbert SE, Harris IA, Maher CG, Spinal cord stimulation for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, issue 3. Art. No.: CD 014789.DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD014789.pub2.

- Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, et al. Overtreating Chronic Back Pain: Time to Back Off? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(1):62-68.

- Carragee EJ, Tanner CM, Khurana S, Hayward C, et al. The rates of false-positive lumbar discography in select patients without low back symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(11):1373.

- Walsh TR, Weinstein JN, Spratt KF, Lehmann TR, et al. Lumbar discography in normal subjects. A controlled, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(7):1081.

- Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1066.

- van der Wurff P, Meyne W, Hagmeijer RH Clinical tests of the SI joint. Man Ther. 2000;5(2):89.

- Sembrano JN, Polly DW Jr (2009) How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(1):E27-32

- Simopoulos TT, Manchikanti L, Singh V, et al. A systematic evaluation of prevalence and diagnostic accuracy of SI joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3): E305-E344.

- Hansen H, Manchikanti L, Simopoulos TT, et al. A systematic evaluation of the therapeutic effectiveness of SI joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2012 May-Jun;15(3):E247-78.

- Newman DP, Soto AT. SI Joint Dysfunction: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2022;105:239-245.

- Frank H Netter, MD Atlas of human anatomy CIBA – Geigy Corporation, Summit New Jersey copyright 1989 ISBN 0 – 914168 – 18 – 5

- DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo TR. Etiology of Chronic Low Back Pain in Patients Having Undergone Lumbar Fusion. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2011;12:732-739.

- Kiapour A, Joukar A, Elgafy H, Erbulut DU, Agarwal AK, Goel VK. Biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint: Anatomy, Function, Biomechanics, Sexual Dimorphism, and Causes of Pain. International journal of spine surgery. 2020;14:3-S13. *(An excellent review article)

- Mitchell B, Rose R, Barnard A. Prolotherapy for sacroiliac joint pain – 12 months outcomes. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2014;18:e90-e90

- Hermans SMM, Knoef RJH, Schuermans VNE, et al. Double-center observational study of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: one-year results. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2022;17:570-570.

- Bertrand H, Reeves KD, Mattu R, Garcia R, Mohammed M, Wiebe E, Cheng AL. Self-Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain Based on a Rapid and Objective Sacroiliac Asymmetry Test: A Pilot Study. Cureus. 2021 Nov 11;13(11):e19483. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19483. PMID: 34912624; PMCID: PMC8665897.

- Buelt A, McCall S, Coster J. Management of Low Back Pain: Guidelines From the VA/DoD. American family physician. 2023;107:435-437.