In a previous article, Lisa Riley, Vice President of Strategic Product and Partnership Development for VitalHub UK, cited how digital healthcare is helping to transform the NHS through whole system integration in planned care, here Stuart Jeffery talks from a customer perspective

There was a line in a Health and Social Care committee report last year, a quote from Amanda Pritchard, which stuck out in it starkness: “Run single waiting lists across an integrated care system, rather than being reliant just on the resources of an individual hospital”. We’re sure many across the NHS have heard this suggestion as we can hear the collective scratching of heads in the face of the rising and lengthening PTLs. It sounds like such a simple idea, shared pathways and resources across a system, a straightforward and practical step that would balance elective demand and move systems towards collaboration. So why is it not in place?

Mutual Aid

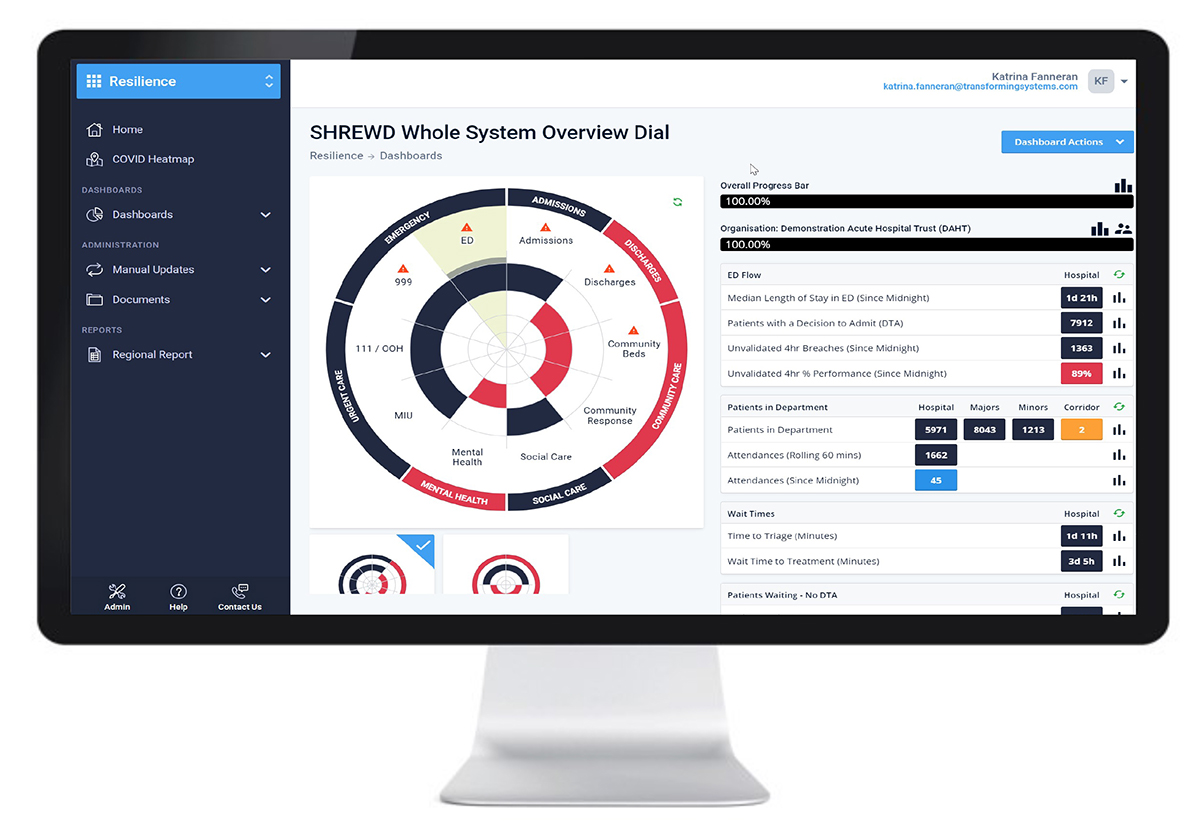

Mutual aid is a term that was used a lot during the covid waves. Support from neighbouring providers in a time of crisis as beds became scarce or, particularly in the first wave, when PPE ran low. Seeing the detail of how pressured other places are, helps with the willingness to provide mutual aid and this system oversight is supported by applications such as SHREWD*.

With the shifting of focus from emergency to planned care and the towering waiting lists which seem insurmountable, what is the place for the mutual aid that Pritchard suggests and how can it be facilitated?

The elective problem may have similar traits to the covid waves and winter surges but fundamental differences in approach and urgency are hampering the ability to call on mutual aid or its elective equivalent, load balancing.

Elective care with its intrinsic organised nature lends itself to a controlled process of planning capacity to meet local demand. There is, or should be, clear data and knowledge of this demand and how capacity needs to flex to meet it. It should be an easily delivered process provided there is sufficient clinical, theatre and bed capacity. A few years ago, this capacity existed but this had started to decrease. Then covid hit, with RTT PTLs now rising quickly, almost to the 6 million mark in England and up from 4.4m pre-Covid, plus the PTLs are a very different shape, with huge numbers of long waiters.

Of course, load balancing isn’t going to solve the waiting list problem, it won’t free up overall capacity at a significant level but what it will do is introduce some fairness across systems. There are some trusts where 8% of their patients have been waiting over a year for treatment, while neighbouring trusts have just a tiny handful waiting that long. The public is right to call for an end to postcode lotteries, particularly when someone in a neighbouring town has a far shorter wait.

Systems are in their infancy and reporting of waiting lists is still done provider by provider. Individual providers are still held to account for their own waiting lists and not for those waiting lists elsewhere in the system. There is no incentive, indeed there is a distinct disincentive, for system working. Why should a provider doing reasonably well with their waiting lists agree to blow their target by taking patients from a struggling neighbouring trust? One answer might be because the NHS is moving to towards integrated care systems, and this affects the whole system. Another is that it is simply better for patients.

Shared data and access

There is also the relative lack of live and shared operational data. Many providers still run with slightly out of date data, information that is a snapshot of a week or so. While live operational information is not a panacea for our collective elective woes, there is real clinical graft and grip needed to maximise the number of people treated, and the development of elective centres would help too. Live operational information does help providers spot trouble early and tweak capacity quickly. We know this is useful for individual providers, so how can this help a system?

Giving access, shared and collective views, to the providers across a system is something that has become acceptable in urgent care, and it needs to become the norm in planned care too. We need a clear change from the regulators to regulate systems rather than providers. Without it, load balancing will remain difficult.

Remember these are patients needing treatment, even if they are not currently your patients. And this doesn’t just apply to Cancer waiting lists. Quality of life, and the consequences and impact of delayed treatment, isn’t captured nearly enough to see the devastating effect long waits are having on people’s lives.

Having an eyes-on approach to planned care, just as we do for urgent care, may help. Applying this across a wider footprint and to help facilitate and maximise cooperation between neighbouring acute trusts, as well as private providers, would be a huge step towards a shared system PTL.

This would be a great win for the providers and the ICSs. Oh, and of course the patients too.

https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5827/documents/67112/default/

Stuart trained initially as a nurse before moving into NHS management. He has worked for both providers and commissioners including ten years in executive director roles in the NHS in north Kent. He now provides consultancy to a number of companies and works as a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Kent.

*SHREWD is a real-time data sharing platform developed by Transforming Systems Ltd. The tool takes complex data from all healthcare providers within a geographical area, and creates live visibility of whole system pressure; a single version of the truth. To learn more about the SHREWD portfolio of data visualisation tools please visit: www.transformingsystems.com

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.

Contributor Details

More About Stakeholder

-

VitalHub UK Group of Companies

The VitalHub UK Group lead health technology focused on data integration in planned and unplanned care, keeping the complex simple.

Editor's Recommended Articles

-

Must Read >> Remote Care in Action: Results from the NHS

-

Must Read >> Digital transformation in the NHS

-

Must Read >> Reducing the NHS patient backlog – A long term plan